5. Titanic (1997)

James Cameron’s technical and financial breakthrough has gotten a bit of a bad rap twenty years after its release. Titanic has become somewhat of a Gone With the Wind of our time, with its love story placed within a historical context, its care of production before story, and its sheer length and scope.

The only difference is that the production in Titanic is not remembered nearly as much as Gone With the Wind’s, and maybe for some understandable reasons (Gone With the Wind could not be matched with its production for many years, whilst Titanic came out when technology was being integrated and constantly bettered). As well, the fact that this film beat L.A. Confidential is just plain silly.

Honestly, give Titanic a retry. It may surprise you more than you would think it would. Some of the story elements will stick out as particularly worse (of course the helmsmen were distracted by Jack and Rose right before hitting the iceberg), so you should be prepared for that.

The production may grip you in a way you simply did not remember. The flooding scenes, the recreation of the entire ship and more are still fascinating even now. James Cameron gets his fair share of flack nowadays, but don’t forget that Titanic dominated the world once (maybe a bit more than it should have, but it isn’t entirely ludicrous).

4. American Beauty (1999)

Life sucks. No one is perfect, and yet we all pretend to be. We all catch the highlight reels of someone’s painfully excruciating existence, and it is suddenly a contest to demean ourselves with when we forfeit the competition.

Sam Mendes’ desire to capture only the brightest moments within misery met its perfect match with Alan Ball’s fascination of the personal anguishes we all share daily. American Beauty is a lie, because most of what is in the film is wallowing in stagnant sorrow. Where did life disappear to? How did we get so old so quickly? Is this what it is all about?

The shattering of the American dream is exciting to watch. The white picket fences remain, and yet Lester Burnham has learned to sprint past them every morning without giving them any sort of attention. Cameras are used as objects of intrusion to capture the bare essences of characters (or garbage that floats in the wind).

One existential crisis results in an avoidance of the shackles of society, and it disrupts the flows of those around Lester. Yes, most of American Beauty is ugly, but the titular beauty is found in the most unexpected places: the infrastructures of the webs created between loved ones, the rubbish left behind that still got invented by humans, and the death that puts a cap on a life that may or may not have been lived to its fullest is still our inevitable swan song.

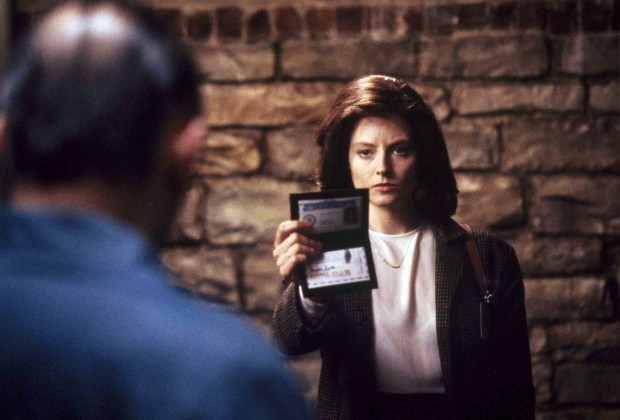

3. The Silence of the Lambs (1991)

Out of every Best Picture winner, The Silence of the Lambs is one of the most miraculous feats. Nowadays, Oscar films are released towards the end of the year to be noticed: Lambs was released at the very start of 1991. Oscar bait films, especially around the early ‘90s, offered sentimentality and connectivity with its audience: Lambs was hideous and repulsive.

Having said all of this, The Silence of the Lambs was a horror film that went against these conditions and has been the last film to win the big five awards (Best Picture, Director, Actor, Actress and Screenplay) thus far. This film truly went against the odds in so many ways.

Of course it did: The Silence of the Lambs is a staple in horror cinema that cannot be beaten. Jonathan Demme’s crime thriller is either through the eyes of its leading cannibal (Hannibal Lecter), its young agent in training (Clarice Starling), or the stalking force that invades each scene with curious eyes. All of the awful tales and gruesome images are only steps towards the ending, where Demme can flaunt his experience from making music videos with ease.

Colours are electrifying yet they suffocate you, the motions of the insects as they fly are almost rhythmic in nature, and the camera swirls around Clarice not as a rockstar but as the next victim. This film will forever be creepy, because Jonathan Demme treated this project not as an excuse to make a horror but as just another day in the office.

2. Unforgiven (1992)

Dances with Wolves brought interest back into the Western genre, but it wasn’t gritty enough. The patriotism was there, and the respect for the American plains was present. However, the ugliness of greed and selfishness was particularly absent in a way that many Westerns would showcase. Clint Eastwood is a central figure of the genre, and if anyone knew how to both truly bring the genre back while closing the doors on his own involvement, it’s him.

This was the last Western Eastwood ever wanted to be a part of, and it is a massive statement. An elderly farmer who was formerly a gun slinger is asked to take part in one more mission. He accepts on behalf of his struggling family, and off he goes into the deep red sunset. This was Eastwood taking a breath and accepting his fate, that he would never take this road again.

The character of Will Munny is expertly written, because he commits one of the greatest role reversals in film history. You root this farmer on, as he seeks clemency for his evil past. Once we get to the ending, Munny becomes the angel of death, with the dimly lit windows behind him acting as his wings. We have been rooting for the devil this entire time, and we wished ill will on the law just because they were going against those that we supported.

Morality is a grey area that can never be perfected, but bloodlust is never justifiable. Unforgiven additionally stars Gene Hackman, Morgan Freeman and Richard Harris, as these acting veterans pull their distant memories and inject them into this picture. Eastwood truly brought Westerns back with this dingy film, and no one could make a Western darker even if they tried.

1. Schindler’s List (1993)

Schindler’s List is the definitive example of film history having been made. A Hollywood studio director (Steven Spielberg) took a step back to forget what he knew about American filmmaking. He looked at world cinema (perhaps The Battle of Algiers, and Come and See) to examine how the rest of the globe examined human turmoil. He created Jurassic Park around the same time to cope, because of the amount of energy that was placed into this motion picture.

Spielberg even refused to accept any financial return for this picture, as he labeled any sort of earning as “blood money”. Schindler’s List was made with complete consideration involved, and it shows. It may not be the easiest watch (many of the deaths in the film still seem far too realistic, even 24 years later), but Schindler’s List is essential viewing for any film fan.

It is borderline impossible to examine every noteworthy aspect of this one. Liam Neeson’s Oskar Schindler is far from perfect, and is as unbiased of a portrayal as you can get; Schindler had a dark side, but it is his change of heart that is projected here, no matter how long it took for that transformation to happen.

Ralph Fiennes has one of the all time riskiest performances as Amon Göth, where he had the task of adding some sort of pathos to an absolute monster. The line up is rounded out by powerhouse work by Ben Kingsley, Embeth Davidtz, Caroline Goodall and more. The prioritization of select Schindler Jews is a genius decision, as you can experience their separate struggles while they represent the different difficulties many faced during the times of the Holocaust.

When we reach the end of the film and see the actual Schindler Jews visiting his grave, that is when your heart will spill the most, since you have watched the nightmares these families were pulled out of by Schindler. Even the people you barely get a chance to see have some sort of a story built up so you never take any of the lost lives for granted (the engineer, and, especially, the girl in the red coat are strong examples).

Schindler’s List is a courageous transformation from evil to good. Schindler was a member of the Nazi party that only cared about what money his factories could bring in. This film shows you the hyper-realistic realizations he faces, where he eventually understands what lives are at stake.

This film was Spielberg’s opportunity to put aside his Hollywood sensibilities, go back to what made him love cinema when he first started out, and find a way to show his appreciation for figures like Schindler and Itzhak Stern who helped save thousands of lives. Schindler’s List transcends filmmaking and becomes a celebration of life and a mourning of death.

This doesn’t even feel like a Spielberg film; hell, it doesn’t feel like a film made by anyone. This is a caliber of cinema that is rarely ever reached, and this is why Schindler’s List is, perhaps, the greatest Best Picture winner of all time.

Rankings of other decades:

Pre-1950 Best Picture Oscar Winners Ranked From Worst To Best

1950s Best Picture Oscar Winners Ranked From Worst To Best

1960s Best Picture Oscar Winners Ranked From Worst To Best

1970s Best Picture Oscar Winners Ranked From Worst To Best

1980s Best Picture Oscar Winners Ranked From Worst To Best

Author Bio: Andreas Babiolakis has a Bachelor’s degree in Cinema Studies, and is currently undergoing his Master’s in Film Preservation. He is stationed in Toronto, where he devotes every year to saving money to celebrate his favourite holiday: TIFF. Catch him @andreasbabs.