9. The Moon in the Gutter (Jean-Jacques Beineix, 1983)

A young, burly, revenge-obsessed stevedore, Gérard (Gérard Depardieu), persistently searches for the rapist of his sister who committed suicide with his own razor, after the attack. On a night of the full Moon, he encounters a wealthy, gorgeous, enigmatic woman, Loretta (Nastassja Kinski), whose alcoholic brother may be one of the suspects. As if blinded by the billboard message “Try Another World”, the two of them get involved into an unlikely relationship.

Relying upon Kinski’s and Depardieu’s physical presence and their magnetic performances, as well as on phenomenal studio sets with exquisite tenebristic lighting, Beineix creates the film of sensual, almost tangible atmosphere occasionally reminiscent of Alain Robbe-Grillet’s works.

Part romantic melodrama and part neo(n)-noir mystery, “The Moon in the Gutter (La lune dans le caniveau)” gets progressively weirder, unfolding in a dreamlike fashion, as the unspecified time and place intensify the feeling of otherness. It is a surreal, visually lavish tour de force whose leisurely pace is in perfect sync with the protagonist’s morose, melancholic mood.

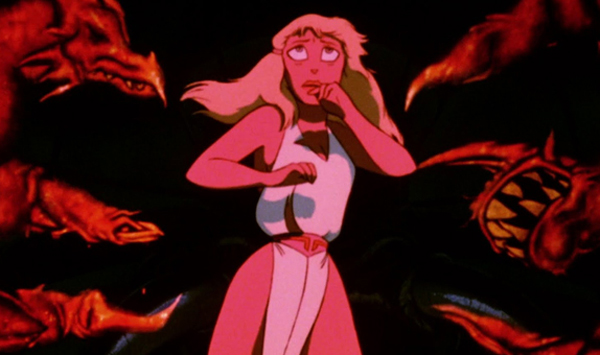

10. Rock & Rule (Clive A. Smith, 1983)

In a future far away, on the war-torn Earth, the humans are replaced by anthropomorphic rats, cats and dogs who has built a new world that looks like it’s stuck in the 80s. As a fresh band of four tries to break through, a “superrocker” (and Mick Jagger look-alike), Mok, begins a X-factor search for a distinctive voice in order to summon the Devil…

Simple in plot and archetypal in characterization, “Rock & Rule” applies the rule of cool and charms you with its spunky and cheeky attitude. Originally intended for the youngest audience, it eventually got the features that aren’t quite kid-friendly – drug abuse, Club 666, a bit of nudity and gelatinous monsters, to name a few.

Its astonishing imagery which looks like a cross between a Disney musical and “Heavy Metal” or some “dirty” Bakshi’s fantasy is accompanied by an excellent soundtrack populated by the likes of Iggy Pop and Debbie Harry (of Blondie). If you’re fond of post-apocalyptic movies and/or classic animation, you will probably love this oft-forgotten gem.

11. Wanderers of the Desert (Nacer Khemir, 1984)

A fiction debut for the Tunisian writer and director Nacer Khemir is a spellbinding fantasy rich with arcane symbolism and baffling action. Beginning with the arrival of a young teacher to a remote, ostensibly abandoned desert village and ending with a mischievous boy falling asleep, it feels like an exotic dream one might have after reading Scheherazade’s stories.

Its title (originally, El-haimoune) refers to an ever growing group of cursed men who leave their families to roam in the wasteland, never to return. Their older relatives keep many secrets from the newcomer (attracted to sheikh’s beautiful and mysterious daughter), whereby the children play an odd game of growing a garden of broken mirrors.

In the picturesque ramshackle surroundings accentuated by vibrant colors and patterns of traditional costumes and interior decor, Khemir spins a hypnotic, non sequitur narrative which blends folklore and ancient legends. Inscrutable and compelling in equal measure, his elusive offering seems like a part of Parajanov’s poetic universe or Pasolini’s “Trilogy of Life”.

12. Farewell to the Ark (Shūji Terayama, 1984)

“People are born half dead, it takes them a whole life to die completely.”

Loosely based on Gabriel García Márquez’s acclaimed novel “One Hundred Years of Solitude”, “Farewell to the Ark (Saraba hakobune)” is the cult director Shūji Terayama’s testament film. As in other works by the Japanese provocateur, the storytelling tends to be pretty obscure, but its very inconspicuousness, along with the technical creativity, is what makes this romantic mystery-drama so inviting.

With his trademark filtered cinematography (featuring many brightly colored details in almost every frame), DP Tatsuo Suzuki gives an unearthly quality to already strange proceedings which involve an incestuous couple and their regressive village of eccentric inhabitants. And J.A. Seazer adds another layer of surreality through his experimental music.

Mainstream audience will probably be bewildered by some stylistic “excesses” and subplots, such as the one with the boy who falls into an ever-growing hole (leading to the Netherworld), only to come out grown-up and become a serial widow-pleaser. There’s also a certain dose of Zulawski-esque madness that will test the impatient, as the themes of sex, guilt, loss, time, superstition and the clash between modern and traditional are contemplated.

13. Lensman (Kazuyuki Hirokawa & Yoshiaki Kawajiri, 1984)

Inspired by the original “Star Wars” trilogy and by Edward Elmer Smith’s character of the same name, “Lensman (SF Shin Seiki Lensman, lit. Lensman: Secret of the Lens)” is one of the dustiest showpieces in the museum of forgotten anime. Available (unfortunately) only in non-Japanese dubs, this wonderfully cheesy space opera deserves a better status.

Being a condensed version of TV series “Galactic Patrol Lensman”, it does have some noticeable narrative jumps, yet the authors barely allow you to breathe between non-stop chases, explosions, fights and rescue missions.

Focusing on the never-ending clash of good (a pilot hero, Kimball Kinnison) vs. evil (a despotic archvillain, Lord Helmuth), Hirokawa and his more famous colleague Kawajiri (Ninja Scroll, Vampire Hunter D) take you on the 25th century intergalactic adventure of epic proportions.

The superb visuals, then novel combination of traditional and computer animation, set “Lensman” apart from the similar anime of the time. Madhouse Inc. team does its best to fascinate and entertain you with their designs, whether it’s high-tech gadgetry or human brain-like spacecrafts.

14. Starchaser: The Legend of Orin (Steven Hahn, 1985)

Yet another example of the 80s camp glory, “Starchaser” is set in the dystopian Mine-World where humans are subjected to the evil overlord (and Mola Ram’s animated counterpart) Zygon. After one of the young miners, Orin, discovers a mythical sword and teams up with the princess Aviana, the smuggler Dagg and a couple of droids, the battle for freedom begins.

As you’ve probably noticed just by reading the synopsis, this film borrows plenty of elements from other sci-fi and fantasy works, but it comes in a package that is so pretty and amusing, you probably (most certainly, if you’re nostalgic for the era) won’t be able to resist it.

Regardless of the cliché trappings and easily predictable epilogue, there’s a lot to enjoy in Orin & Co. trials and tribulations, from top-notch old-school artwork, through synth tracks and exuberant orchestrations, and all the way to the likable protagonists, such as the seductive fembot Silica.

15. The Treasure of Swamp Castle (Attila Dargay, 1985)

If Walt Disney had been Hungarian admirer of Albert Uderzo of “Asterix” fame, his animated films would have looked like “The Treasure of Swamp Castle (originally, Szaffi)” – a loose adaptation of Mór Jókai’s novel “The Gypsy Baron”.

Set in the 17th century, it revolves around the search for the buried treasure of Ahmed Pasha and the romance of his lost daughter Szaffi and Jónás Botsinkay, an impoverished aristocrat who returns home from exile.

Wittily, skillfully and dynamically told by Attila Dargay, this pseudo-historical fairy tale (or rather, a social satire in a clever disguise) is filled with lively (and chatty) characters – kudos to exquisite voice actors. They all have an important part in creating a jovial atmosphere, alongside the music by Johann Strauss II (whose operetta is also based on Jókai’s book) and lush animation which opens the door to the magical world.

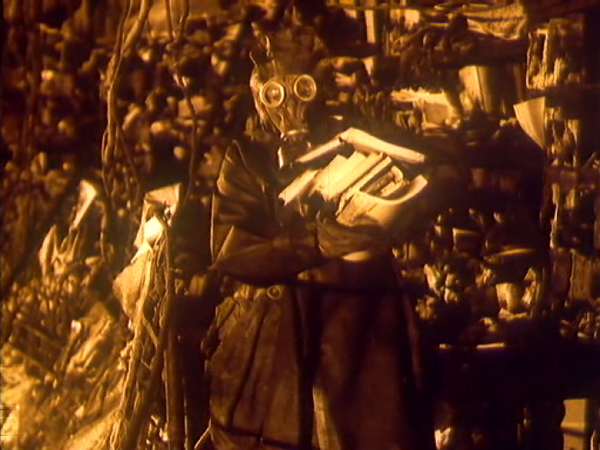

16. Dead Man’s Letters (Konstantin Lopushansky, 1986)

“Dead Man’s Letters (Pisma myortvogo cheloveka)” focus on a group of people in the basement of a dilapidated museum who try to survive the aftermath of nuclear catastrophe caused by a human and a computer error. All the while, one of them, a Nobel-laureate scientist, “writes” the letters that will never be read, as they’re addressed to his dead son.

A poetic SF-story is shrouded in deep melancholy – hope and faith are in the throes of death. Grim, leaden and pessimistic, Lopushansky’s post-apocalyptic drama is shot in dreary, Tarkovskian sepia-tones, with a few grayish scenes serving as a bitter “refreshment”. Gorgeous in its desolation, the imagery of despair, such as the “mountains” of tattered books in a flooded library, reflects the Ultimate End.

Immaculately directed, expressively acted and poignantly written, particularly when it comes to the protagonist’s “mind letters”, the film is imbued with symbolism the old-school Russian cinema is known for.

17. The Rose King (Werner Schroeter, 1986)

A darkly romantic melodrama “The Rose King (Der Rosenkönig)” is Werner Schroeter’s last goodbye to his muse, Magdalena Montezuma, who died shortly after the shooting ended. In her last role, she portrays a mentally unstable widow, Anna, who moves to a coastal town in Portugal to grow roses together with her adult son Albert (Mostefa Djadjam).

Their already tense relationship cracks soon after the arrival of a young servant, Alberto (Antonio Orlando, one of the scapegoats from “Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom”), whom Albert kidnaps, glorifies and eventually deifies.

Schroeter uses a simple plot as an excuse for the series of pompous, dreamlike vignettes in which Baroque art meets Poe’s verses. As the lyrical dialogue intertwines with religious and homoerotic iconography, the soundscapes are formed by fado, opera and Arabian traditional music.

The portrait of mother’s overprotective love and her boy’s rituals of passion is enriched with oft-cryptic symbols and the signs of inexorable decay which Montezuma boldly defies. Her lisping and piercing gaze are hard to resist as much as the striking aesthetics of her heroine’s kingdom of roses inhabited by the ghosts of longing.