18. To Sleep So as to Dream (Kaizō Hayashi, 1986)

In his feature-length debut, Kaizō Hayashi pays a loving tribute to the silent films and to Japanese narrators called Benshi who once provided live narration during the screenings. “To Sleep So as to Dream (Yumemiru yōni nemuritai)” is not entirely voiceless, but it is fascinating.

Starting as a detective mystery spiced with a pinch of humor and turning into a meta-fantasy with a touching finale, it is like a missing link between “Sunset Boulevard” and “Millennium Actress”; a meditation on loss, memories, identity, the nature of cinema and the transience of time.

The basic plot involves a private eye, Uotsuka (whose favorite food are hard-boiled eggs) and his whacky, yet skillful assistant, Kobayashi, trying to track down an aging actress’s missing daughter. However, the things are not at all what they seem to be (as the obscure clues suggest) and the girl, Kyoko, is actually a personified metaphor which can be interpreted in at least three different ways.

As we try to solve her riddle, reality, illusions and dreams collide in stark B&W.

19. Lily C.A.T. (Hisayuki Toriumi, 1987)

The second and last piece of Japanese gorgonzola on the list is one of more competent “Alien” imitators from the 80s, considering its direct-to-video production values and economic running time of less than 70 minutes.

“Lily C.A.T.” is the brainchild of Toriumi and his screenwriter Hiroyuki Hoshiyama who dare to borrow some elements from another horror milestone (The Thing), only to incorporate a fresh concept of “time-jumpers” and add a distinctively Japanese flavor to the rip-off proceedings.

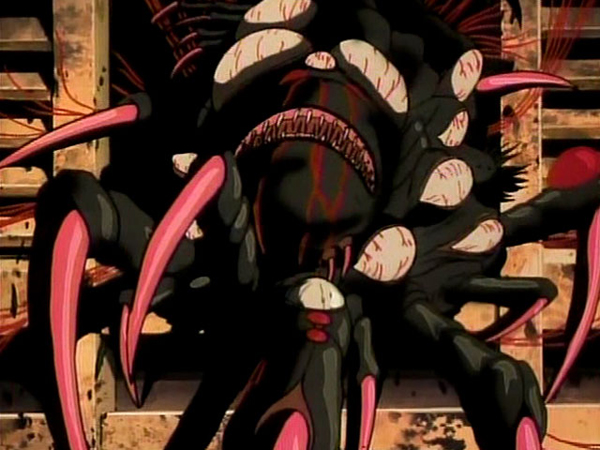

Modernizing the myth of bakeneko (a cat demon), the aforementioned duo takes us on a space trip that doesn’t go quite as planned. During the 20-year-long period of cryogenic hibernation, the crew and the passengers are joined by a mysterious alien bacteria. When they awaken, the “stowaway” goes into a predator mode…

… and it’s really terrifying once it absorbs the throwaway characters and starts destroying the ship. The famous illustrator Yoshitaka Amano does a great job at freaking you out with the monster, while his colleague (and then a rookie) Yasuomi Umetsu, provides a distinct design for the racially diverse cast. The artwork for dread-inducing backgrounds is commendable as well.

20. Déjà Vu, aka Reflections (Goran Marković, 1987)

An introvert piano teacher, Mihailo (Mustafa Nadarević’s unforgettable performance), works in an educational center for adults and leads a solitary life. But, his humdrum existence changes forever with the arrival of a young, capricious modeling instructor, Olgica (Anica Dobra, excellent), at his collective. The two of them start an awkward relationship which opens Mihailo’s old wounds and leads to bloodshed…

As its clever title suggests, “Déjà Vu (Već viđeno)” doesn’t bring anything novel in the terms of the deeply-traumatized-child-becomes-psychopath plot, yet it remains fresh to this day, considering the social circumstances in Yugoslavia of the time and in Serbia now. The film covers a few decades without ever feeling convoluted, seamlessly merging a thoughtful character study, deliberately paced psychological horror-drama and the metaphor of a crumbling country.

In addition to being expertly acted, knowingly directed and meticulous in its attention to details, it features the eerie score and elaborate cinematography which establish the unnerving atmosphere so thick you could cut it with a knife. Undeniably, it is not only one of Marković’s best, but one of the most exemplary works of ex-YU cinema.

21. Days of Eclipse (Aleksandr Sokurov, 1988)

Cryptic and genre-defying, “Days of Eclipse (Dni zatmeniya)” centers on Dmitry Malyanov – a young and ambitious doctor stationed in a remote Turkmen village. His attempts at research are thwarted by the series of bizarre events which could be caused by some invisible higher force or heat-induced hallucinations.

With the looks of a blonde mannequin, Aleksei Ananishnov (who will later appear in Sokurov’s oneiric drama “Mother and Son”), is perfectly suited for the role of a newcomer whose ideas and principles are conflicted with the locals’ primitive customs. Socially limited to his dispirited sister, paranoid friend and suicidal erudite neighbor, Dmitry falls into a state of existential disorientation.

Elusive narrative threads are intertwined into a dead-end nightmare, as the misty soundscapes and bleak cinematography dominated by sepia-tones establish a heavy atmosphere of despair, inanity, alienation and numbness (of spirit and society).

Like a designer of dreams, Sokurov depicts reality from a distorted angle and delivers a layered work of brutal, yet hypnotic beauty.

22. Dogra Magra (Toshio Matsumoto, 1988)

“O fetus, why do you undulate? Is it the knowing of your mother’s heart that fills you with dread?”

Based on the novel of the same name by Yumeno Kyūsaku (known for an avant-garde approach to writing), “Dogra Magra” is Matsumoto’s third and, unfortunately for the surrealism aficionados, last feature. It is an impenetrable psychological mystery created around a young, amnesiac man, Ichiro Kure, who might have killed his mother and fiancé and who is left at the mercy of two eccentric, possibly crazy doctors, Masaki and Wakabayashi.

According to the latter shrink, the title refers to “a chant used by a secret Christian sect in Nagasaki”, but that seems to be just one of many red herrings in the film that plays like a dizzying nightmare (maybe, of an unborn child?). It’s easy to get lost in the knotty narrative labyrinth where it’s impossible to tell what is reality and what is a schizophrenic hallucination.

Told from the perspective of a fractured mind, “Dogra Magra (or Dogura Magura, as the Japanese pronounce it)” mesmerizes you with cacophonous music and poisonously greenish images (Tatsuo Suzuki, brilliant as ever), as it pulls you deeper into the whirlpool of madness.

23. Mág (František Vláčil, 1988)

A melancholic swan song by František Vláčil (Marketa Lazarová) is dedicated to the early deceased Czech poet Karel Hynek Mácha (1810-1836) who achieved fame only after his death.

Several chronologically scattered episodes from Karel’s youth are interconnected by his foreboding visions and gloomy passages from his epic poem “May” (in the original transcription, Mág) recited by the veteran Rudolf Hrusínský (Kopfrkingl from J. Herz’s darkly humorous drama “Cremator”).

This idiosyncratic biopic of autumnal atmosphere is primarily focused on a turbulent, jealousy filled romance with Eleonora (Lori) Somková, as well as on the animosity towards Josef Kajetán Tyl, a dramatist who frequently criticized Mácha’s style for being chaotic and confusing.

It provides the poet’s lyrical portrait rendered with assured strokes, especially in the scenes which depict him as a solitary man enamored with nature. In the starring role, Jirí Schwarz shows deep understanding of his complex, somewhat contradictory character.

24. Moon Child (Agustí Villaronga, 1989)

“Nothing existed yet, but his heart had opened to receive a solitary moonbeam which then fell on the mother’s lap.”

David, a cherub-faced orphaned boy, firmly believes that he is a titular hero from an African tribe’s prophecy. When he gets adopted by a Nazi-like, semi-occult and pseudo-scientific organization, he learns that the legendary child is yet to be born. A strange thought (of a second birth) comes to his mind and triggers an escape and a journey to Africa…

Fans of Dead Can Dance are certainly already aware of this peculiar film, since the band provides the haunting (and unobtrusive) score, whereby the singer, Lisa Gerrard, plays a big part in the story – ambiguous and magical in equal measure.

Visually inspired, occasionally geometrical in frame composition (especially during the first half), “Moon Child (El niño de la luna)” blends childlike fancy and esoteric concepts into a mildly sinister and mystical fantasy, as viewed through the prism of autism.

Intimate, mystical, blue as David’s eyes and unapologetically hermetic, it depicts the lengths one will go to achieve their dream.

25. Warsaw Bridge (Pere Portabella, 1989)

“I write to be read, and I can continue writing because I am read.” – says the author of the fictive, award-winning and probably unfilmable novel “Warsaw Bridge (Pont de Varsòvia)” that might be the basis for Portabella’s highly experimental narrative.

However, the surreal “story” is not about this book, nor it is about solving the mystery of a scuba diver (the writer’s friend) found dead in a burnt forest (although a darkly comical answer to how he ended up there is the epitome of a wonderfully deadpan, intentionally anticlimactic epilogue).

The film is a witty, intellectual ode to literature, sculpture, architecture and (dying?) nature, as well as an enigmatic exploration of creative process in the series of neatly organized sequences bridged by a few musical interludes of weird juxtapositions.

In a non-linear, stream-of-thoughts fashion, Portabella makes digressions that are amusing in their high-brow seriousness and simultaneously puzzling and rewarding, such as the dead fish married to an aria-lip-syncing couple or an orchestra who performs from the balconies above the busy street, with a video-monitored conductor standing on a high platform.

Author Bio: Nikola Gocić is a graduate engineer of architecture, film blogger and underground comic artist from the city which the Romans called Naissus. He has a sweet tooth for Kon’s Paprika, while his favorite films include many Snow White adaptations, the most of Lynch’s oeuvre, and Oshii’s magnum opus Angel’s Egg.