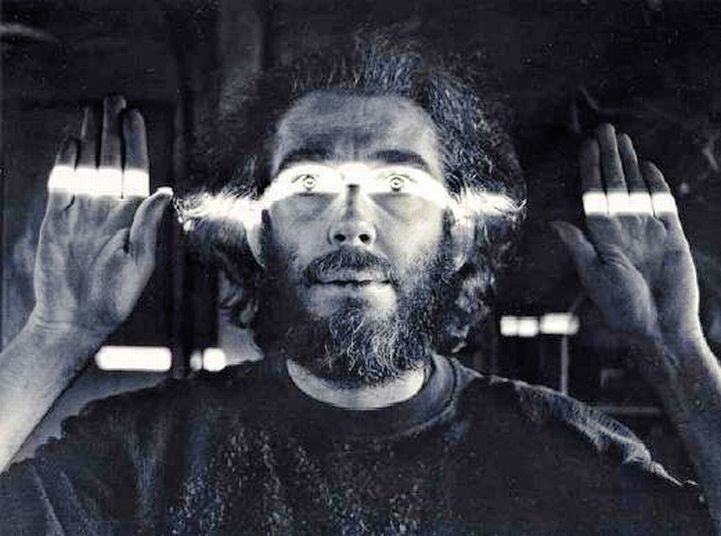

9. Zorns Lemma by Hollis Frampton

The second film of Hollis Frampton’s on this list is also quite simple. The film is an hour and is the absolute example of cinema being a pattern to discern. Images of signs and books flash before the screen with words that begin with each letter of the English alphabet, in succession. This pattern repeats itself over and over as words beginning with each letter of the alphabet are found in different parts of the city Frampton lived.

Gradually, certain words beginning with particular letters of the alphabet cease to be found. This is when Frampton introduces images to replace certain words. Eventually, the entire 26 word English alphabet is replaced with images from the world. Language has been transformed into cinema.

It can be tough to sit through a pattern that one knows will repeat over and over until a given running time has commenced, but this is Frampton again stripping cinema down. This film is a lesson in structure, how it exists in any sequence of images.

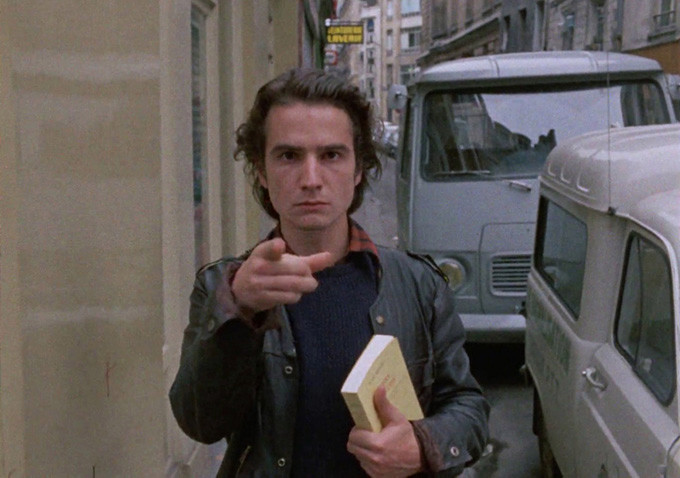

10. Out 1 by Jacques Rivette/ Suzanne Schiffman

This titanic work from iconic French New Wave filmmaker Jacques Rivette is quite a task to watch and describe. The film is the longest of this list at over 12 hours long (found on Netflix) and vaguely follows two separate acting troupe’s as they rehearse and rehearse and go through acting exercises without any intention of performing for an audience asides from themselves.

At the same time, a deaf-mute named Colin, played by Jean-Pierre Leaud, begins following a string of clues that indicate to him a secret society may be in operation. And, at the same time, a con-woman named Frederique, played byJuliet Berto, also begins following clues that lead her down a path of discovery.

The film is an exercise in extreme patience as it’s clear the acting troupe, along with the deaf-mute and the con-woman, are all searching for something. Exactly what they are looking for is a matter that takes hours of the film’s running time to get to.

Cinematic narrative practically does not exist on a canvas of this size and in its deliberateness, Out 1 shapes into one of the most rewarding and confounding experiences a film viewer could go through.

11. Emperor Tomato Ketchup by Shuji Terayama

Avant-garde artist Shuji Terayama put together a prolific career of creating all sorts of art including making many short and feature films. Like his other films, Emperor Tomato Ketchup is a highly unique film vision that defies an easy description.

The film is about a world in which children have taken over and adulthood has become a crime. This is made clear through the voice-over which describes the stresses of living under these conditions as absurd imagery floods the screen of children soldiers policing the streets, rounding up adults.

One of the distinct traits of Terayama’s cinema is the bold use of a dominant color over his images. A vignette of sorts opens the film seeped in green, as images of young men flexing their muscles are cut together with images of clocks, a woman ritualistically dancing, and an ominous, ambient theme plays over the juxtaposition.

Terayama is similar to Anger in that he mixes images with music or sound and disconnects what is on screen from what is being heard, so diegetic sound does not exactly exist.

12. Jeanne Dielman, 23 Commerce Quay, 1080 Brussels by Chantal Akerman

A more obvious film to populate a spot on a list like this is of course Chantal Akerman’s legendary film. The film has received plenty of acclaim over the years and rightfully so, it is revolutionary.

It is about Jeanne Dielman, a widow that maintains her routine as a housewife over the course of three days, depicted in a running time that is over 3 hours 20 minutes . On top of cleaning and cooking she has men over and sells her flesh for cash. Over the course of three days in her life an indisputable tension begins to build, a craving for Jeanne to escape the monotony of her regimented prison.

The film is a brutal examination of routine, of entrapment within a given schedule, as well as entrapment within the frame of a movie screen. Akerman is one of the pioneers of cinematic art in that she proves her characters are trapped, they are images on an unmoving screen. No camera movement occurs in Jeanne Dielman and it is exactly through staticity does a need to escape arise.

13. The Travelling Players by Theo Angelopoulos

From the Greek legend comes a vast and impressive work in which historical eras come to combat one another on the screen. The film can be described as about an acting troupe that gets lost in time, coming face to face with Fascists, Nazi’s, and Communists of eras existing through a 20 year time span.

Angelopoulos is known for his extended shots and this is one of the best examples of his work in which eras come together within single, unbroken shots that pan years into another era. At 3 hours 50 minutes long the toughness of the film comes from its longer running time of course but also through the fact that characters themselves seem to become lost, slipping out of the narrative. It very vaguely follows them in wide, sweeping shots throughout the film and sometimes it becomes difficult to remember who is who.

Like the Straub’s, Angelopoulos made many films concerning era and time and it fighting itself, existing all at once as opposed to one period, followed by then another. The contrasting aspect of Angelopoulos’ films to the Straub’s of course has to do with his necessity for making longer running films as opposed to the generally shorter films of Jean-Marie and Daniele.

14. Salo, or the 120 Days of Sodom by Pier Paolo Pasolini

Necessarily featured here, Pasolini’s opus to his own cynicism towards humanity is one of the treasures of inaccessible cinema. Michael Haneke himself considers the film one of the greatest ever made yet has only seen it once, claiming to have become physically and mentally sick as a result of a viewing of the film upon its release in the 1970’s.

To sum up the film a good friend Nicholas Swanton once said it’s about “how it’s hard to have a good time” and Pasolini could not have agreed more. A group of 9 young men and 9 young women are rounded up by Mussolini Fascists and brought to Salo, where they are psychologically and physically tortured for entertainment, essentially. The Fascists laugh and boast over their power, often arguing various sadistic topics in joy.

The film is absolutely a must-see. It is a brutal watch full of highly disturbing content in which people abuse others for the pleasure of being the abusers, and could not be a more cutthroat examination of human beings as a species. It is a backbreaking experience that’ll make anyone who watches a better person.

15. Angst by Gerald Kargl

Gaining status as a result of Gaspar Noe’s adoration of the film, Gerald Kargl’s unnerving work is a study of nature vs nurture. The film must understand the process a person goes through to become a deranged murderer.

When seen with the opening prologue, Angst sets up its lead character as a lunatic ready to kill as many people as he can. He murders an elderly woman and goes to jail for 10 years, this after being abused as a child and often displaying signs of being psychotic throughout his life.

Quite a violent and tense film to watch but the music and cinematography provide plenty of beauty (keep in mind this film inspired much of Gaspar Noe’s films) and prove that Kargl was quite the talent as a filmmaker.

16. Shoah by Claude Lanzmann

Another indisputably titanic work is Claude Lanzmann’s film on the Holocaust. It is over 9 hours long and features no stock material, opting to only feature people as they were upon filming. That is to say the film still retains a horrifying brutality, the stories that these survivors tell are impossible to eradicate from the mind. They are vivid, terrifying.

But as a result of the film being a bunch of people speaking, and often times, telling their first-hand accounts, Shoah is surprisingly watchable. The film really grips a viewer as they detail the horrors of what happened during the Holocaust. Incredible feat of extensive documentary, no doubt this one is one of the most profound experiences in cinema history.

17. Die Antigone des Sophokles nach der Holderlinschen Übertragung fur die Buhne bearbeitet von Brecht 1948 (Suhrkamp Verlag) by Jean-Marie Straub/ Daniele Huillet

On here mostly as a result of the title which in German is quite long. Simply titled Antigone in English, and on YouTube, this second film of the Straub’s is no where near as difficult to grasp as Not Reconciled but still retains their classic, distinct style.

The film is a cinematic rendering of a portion of the Oedipal cycle, in which a King rules the land and discusses the political happenings with his counsel. Outlandish acting and non-stop talking, all events that happen in the kingdom occur off-screen, described and discussed by those on-screen.

Only about 90 minutes long but is an intellectual task to retain all the philosophical implications of what is discussed but when digested, the Straub’s film resonates as one of their most insightful works.