Every year, an Academy Awards nomination for Best Director calls attention to the person behind the camera whose complicated job it is to bring their specific vision of a story to life on-screen. This nomination also pulls focus on the oeuvre of these directors, however expansive or brief a filmography they may boast.

This year’s Best Director nominees have diverse film histories: some have risen through the ranks of indie films to attain the highest honor that can be bestowed upon a director in the industry while others have been making films for decades and have been nominated for their previous work before.

Whatever their background, for these highly esteemed nominees, their past efforts–no matter how obscure or well-known–are reflections of the work that they would one day produce to nab a nomination this year.

Whether low-budget, personal projects or high-budget, slick affairs, earlier films made by this year’s Best Director nominees all have noteworthy earlier movies that show either the promise of what was to come later in their careers or represent highlights as already established filmmakers.

While some of these directors have a long history of films to reflect upon, or if their nomination this year signals an emerging talent, all of the nominees this year have a notable film or two lurking in their past. Here are some suggestions for the inquiring cinephile to explore when considering the overall merits of this year’s Best Director nominees.

5. Damien Chazelle, Guy and Madeline on a Park Bench

Focusing on the rocky relationship between an aimless young woman (Madeline) and a trumpet player (Guy), this black-and-white indie was the first full-length feature from Oscar-nominated Director Damien Chazelle (La La Land).

Like his most recent film, his debut focuses on the life of struggling musician Guy and maintaining a relationship with the woman he loves. Meanwhile, Madeline goes on a journey of self-discovery, trying out new relationships, and deciding what she wants out of life.

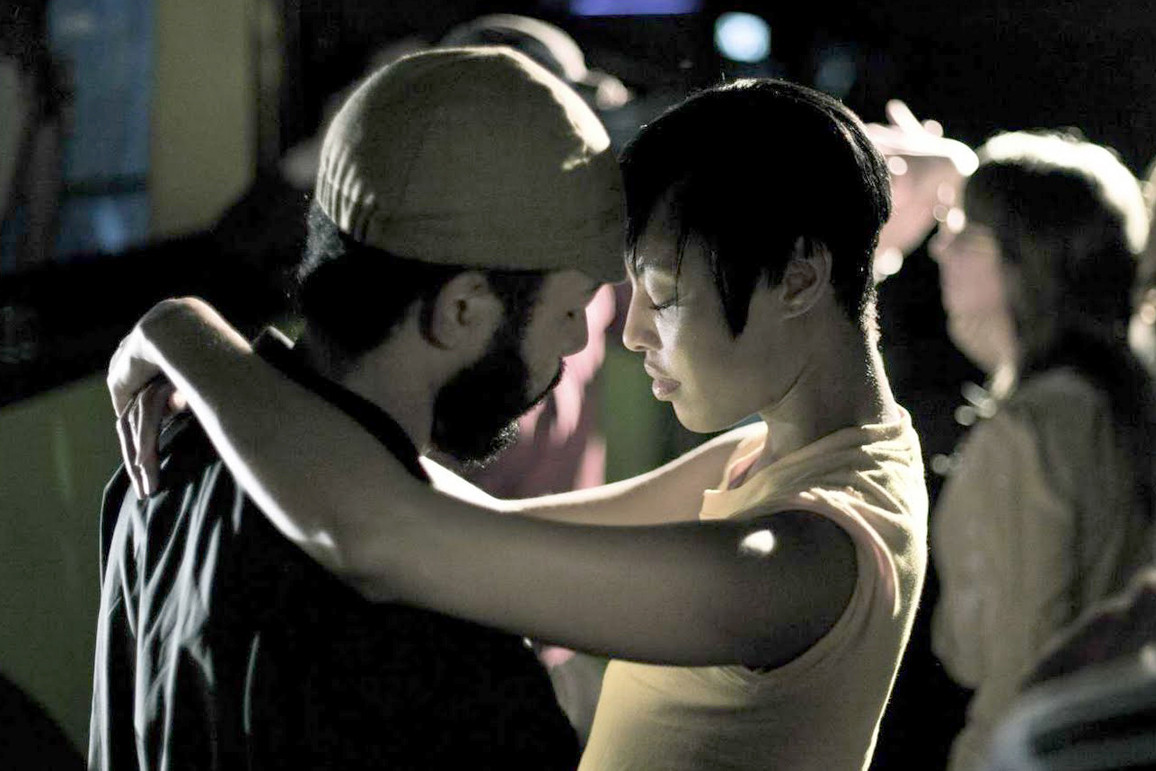

Shot in cinema verite style, Guy and Madeline on a Park Bench (which was written, produced, and directed by Chazelle) evokes Godard’s documentary-like style with an active lens that examines the up-close features and emotional reactions of its subject. Vignettes of performers of all types–on the street, at parties, in conversation, and by themselves–give the film a much more realistic grounding than the flights of fancy and glitz that the musical sequences of La La Land are prone to.

This is not to say that the film is grounded in reality: characters break out in song (also written by Chazelle) while walking down the street, and a choreographed dance turns a closed restaurant into a stage for its staff in one of the musical highlights of the film.

While Guy and Madeline break up and she seemingly moves on with her life, Guy is left wondering if he had made a mistake in letting her go and the film ends with a question of whether they’ll reconcile their romance or go their separate ways.

Filmed on 16mm stock and shot on a miniscule budget, the movie began as a student film while Chazelle was at Harvard and features performances by non-professional actors (but professional musicians). It is an intimate peek into the ups and downs of life and love between two people trying to figure out what to do with themselves and each other.

While a hit at festivals, its small nature led to a limited theatrical run. Described as a “mumblecore musical,” it’s almost the opposite of Chazelle’s larger, more confident La La Land but still hits a sweet spot that’s undeniable.

4. Barry Jenkins, Medicine for Melancholy

With the release of his fluid, moving depiction of the life of an American black man from childhood to adulthood, Barry Jenkins was hailed as a fresh new voice in Black Cinema and his film, Moonlight, has been nominated for eight Academy Awards this year, including Best Director and Best Picture.

While the revelatory quality of Moonlight has earned critical acclaim and serious commentary in the press, Jenkins’ debut, Medicine for Melancholy, has been overlooked in assessments of the director’s burgeoning career.

Produced for $15,000, this movie examines the relationship between two strangers who engage in a one-night stand and spend the next day together discussing their views and positions as minorities in the predominantly white hipster San Francisco culture that they live in.

As much a film about romance as it is about identity politics, the two leads (Tracey Higgins and Wyatt Cenac) give natural performances as two young African-Americans–she more self-assured and less affected in her role among white culture, and he more wary and cynical about such definitions.

A small movie filled with a lot of ideas and carried off effortlessly by its grounded tone, it leaves the viewer trying to work out the often difficult-to-discern puzzle of relationships and racial identity in the 21st century, much like the two leads spend the film discuss and try to work out between each other.

A notable Sundance entry, Medicine for Melancholy is a pared-down look at the awkwardness that comes with one-night stands, opposing viewpoints between two people whose racial backgrounds force them to pick sides, and the precarious nature of attraction.

While Jenkins’ follow-up was a national phenomenon when it was released, his debut is a more intimate picture that features winning performances from the two leads and an urbane look at the subtle navigations of class and culture that minorities have to negotiate daily in American society.

3. Kenneth Lonergan, You Can Count On Me

After paying his dues writing middle-of-the-road fare like Analyze This, Analyze That, and The Adventures of Rocky and Bullwinkle, director Kenneth Lonergan scored critical acclaim for Manchester by the Sea, which is nominated for six Academy Awards this season, including Best Picture and Best Director. But before detailing the adventures of moose and squirrel, Lonergan wrote and directed an indie hit at the turn of the century called You Can Count On Me.

Starring Laura Linney as a young single mother and Mark Ruffalo as her wayward brother, this slice-of-life film details the struggles of Linney’s character, Sammy, as a single mother in a small town in upstate New York.

When her straggling brother Terry visits her after years of silence out of financial desperation, and when circumstances involving his girlfriend (to whom he sent the money he borrows from Sammy) takes a downturn, Terry ends up staying with his sister and her son. While Sammy makes advances and missteps in her love life, Terry bonds with her son and eyes the possibility of living a normal domestic life for the first time in years.

Confronting each other’s shortcomings and their own, both grow–if only a little–by the film’s end, and even for its melancholy tone, there is something universally relatable about the human-level concerns of its protagonists and the gentle empathy of dealing with family members in adulthood.

The film was by no means ignored or underseen: upon its release, it was a certifiable indie hit, hailed as one of the best films of the year by critics and winning a slew of awards along with being nominated for two Academy Awards that year (Best Actress for Linney and Best Original Screenplay for Lonergan).

However, nearly two decades have passed since its release and its initial critical buzz has long since faded. If one enjoyed Manchester by the Sea, than this film will be an endearing view–and possibly even surpass your estimation of his latest work.

2. Denis Villeneuve, Incendies

Director Denis Villeneuve has had a long and interesting career as a filmmaker: in his active 20 years as a director, this French-Canadian has shot 10 feature-length films, including the upcoming Blade Runner 2049.

Nominated this year for Best Director for Arrival, up until 2013’s Prisoners his work was mainly confined to Canadian features that have been underseen in the United States. While a shortlist could be made of his films to track down (Maelstrom, Polytechnique, and Enemy among them), Incendies is possibly the best entry point into this fascinating director’s oeuvre.

Released in 2010, this mystery-drama involves fraternal twins Jeanne and Simon who, upon the death of their mother, find out they have a previously unknown brother and a father who they thought was long-dead. What follows is a plunge into the strict Islamic culture of the Middle East as they try to sort out their mother’s shocking past that involves, among other things, fundamentalist terrorism, the diktat of Sharia Law, and the disturbing origin of their conception.

A heavy plot, entrancing cinematography, and a compelling mystery make Incendies a fascinating film with which to engage. Its cool, clinical aesthetic and cinematic flourishes are reminiscent of Christopher Nolan’s signature style, and Villeneuve’s film makes you wonder why foreign films aren’t more widely distributed in the United States.

It was acclaimed upon its release, winning numerous awards in various countries, and was nominated for Best Foreign Language Film at the 83rd Academy Awards. A masterful work with an important trans-cultural message to relate, Incendies is one of the many worthwhile films in Villeneuve’s body of work to investigate further.

1. Mel Gibson, Apocalypto

While Mel Gibson may not have the best reputation in popular culture at this point, what with his numerous highly offensive public and personal tirades over the past decade, the man is a fine director.

Despite personal beliefs, The Passion of the Christ is still the most intense film ever produced portraying Jesus Christ’s suffering during the crucifixion while Braveheart is a true epic whose sweeping visuals relate the magnitude of William Wallace’s resistance against British oppressors in Scotland in the 13th century.

This year, he’s nominated for the little-seen Hacksaw Ridge, a historical drama based on the true story of a conscientious objector who saved 75 men without engaging in direct combat during the Battle of Okinawa.

Gibson’s interest in singular protagonists–particularly those that go through a harrowing ordeal–has been a running theme in his films, and 2003’s Apocalypto is perhaps his most grounded effort along those lines.

Set in 1511 in pre-Columbian Yucatan, a group of Mesoamericans–including central protagonist Jaguar Paw–live off the land and in relative peace as a tribe until a raiding force decimates their village and enslaves their people, including Jaguar Paw, while his pregnant wife and young son evade capture by hiding. Along his journey to the Mayan city, Jaguar Paw witnesses razed forests and a village that’s infected by plague. There, a young woman close to death prophesizes the fall of the Mayan empire.

Upon entering the great Mayan capital city, the women are sold into slavery while the men are to be sacrificed atop a ziggurat, but a solar eclipse delays the sacrifice. Instead, the men are promised their freedom if they can survive being used as target practice; Jaguar Paw escapes into the jungle and a group of men are sent out to hunt him down.

Trying to both evade death and get back to his wife and son, Jaguar Paw sets traps for his persecutors that take them down one by one. By the end of the film, conquistador ships are glimpsed landing on the shoreline, the prophecy having passed, and Jaguar Paw–now reunited with his family–disappear into the jungle to find a safe place to live.

The realism that Gibson imbues the film with is surprising, even for a big-budget Hollywood production. The naturalistic rendering of the Mayan people and their life in the rainforest (for good or ill), along with the depictions of their more crowded and materially wealthy metropolitan areas, provides a sweeping look at a once-great civilization in decline.

Examining the cycles of violence that perpetuate and destroy civilizations, the devastating effect human endeavors have on the environment, and the universal drive to survive and protect one’s family from danger, Apocalypto was widely praised by both critics and filmmakers alike, with Quentin Tarantino and Martin Scorsese calling it one of the best films of that year.

While it faced some criticism for its historical inaccuracies and depiction of the Mayans as a violent and cruel people, its dialogue is all spoken in Yucatec Maya language and its cast is comprised of Mexican and Native American actors. With its grand themes and strive towards historical authenticity, beautiful cinematography, and intriguing glimpse at a long-lost world, Apocalypto is as close to a masterpiece as Gibson has ever approached either before or since.

Author’s Bio: Mike Gray is a writer and academic from the Jersey Shore. His work has been featured on Cracked and Funny or Die, and he maintains a humor film recap blog at mikegraymikegray.wordpress.com.