3. Revised Social Realism

Threads was written by the social realist writer Barry Hines, perhaps most famous for his novel a Kestrel for a Knave (1968) which he later adapted for Ken Loach’s 1969 film Kes. Being from South Yorkshire himself, Hines harnessed t’idiosyncratic dialect of the region as well the political mood, creating believable characters which he eventually drags into an unimaginable situation.

The film begins very much like a kitchen sink drama, working class Jimmy impregnates the middle class Ruth. With their class boundaries and their non-marital status, how can they possibly raise this child? The film depicts the young couple move into their grisly new flat where they discuss wallpaper along with their moderate hopes and dreams. In this period the conservative government often emphasised the importance of the family in a righteous and dogmatic way.

One interesting sequence in the film is where Jimmy discusses the necessity of marrying Ruth now she is with child which is met with a certain level of ambivalence by his parents. Jimmy’s mother, perhaps a product of the free love of the 1960s, chastises him for trying to settle down so early, which is only met by Jimmy’s sanctimony of ‘what is right’. All this however is meaningless as after the bomb drops, family becomes less of a social construct and more a non-existent abstraction.

From quite a conventional opening, Threads turns into a relentless science fiction film which still manages to cling on to the values of realism. But instead of focusing on the day to the day struggles of a working class family in Sheffield it focuses on the day to day struggles of a pregnant women in a nuclear wasteland. Some of the images conveyed in the film such as the dilapidated buildings and the heavily disfigured victims are evocative of other science fiction texts which focus on the nuclear holocaust such as The Omega Man (Boris Sagal, 1971) or the popular videogame series Fallout (1997-Present).

The protagonist’s position changing hands to Ruth is indicative of the 1980s ‘state of the nation film’. Jimmy’s working class hero character is seemingly of a cinematic era which was beginning to fade as the decade began to focus on more non-white, homosexual characters as well as women.

Although it must be said, it is rather interesting that the film chooses not to discuss race or sexual orientation at all, considering these were both large and prevalent themes in 80’s British cinema. But having said this, the film should not necessarily be criticised for it, as it harnesses all of its focus onto the nuclear issue as well as the representation of a city going through changes, which we will come to. Perhaps too many thematic cooks (thieves, wives and lovers- sorry) would spoil this atomic broth.

4. Consumerist Critique

For some, the 1980s were seen as a time for great economic success. Certainly within the financial sector after the so called ‘big bang’ in UK banks in 1986. However, the country still had a high inflation rate which the conservative government were hell bent on lowering even if it meant cuts to public services. Within this time also, was a rise in the so called ‘service class’ as the working class began to diminish. Ruth is exemplary of this change, whilst traditionally she perhaps wouldn’t have worked, in Threads she has a job at a local supermarket and her own economic freedom.

This rise of private companies and service based jobs as well as further production of consumer goods seem to haunt the edges of the film, being used to show a national distraction when in times of political turmoil. This is seen with the siblings of Jimmy who, despite being quite young, seem enraptured by entertainment technology. Jimmy’s sister listens to her Walkman while important radio broadcast plays throughout the house, Michael, his younger brother, plays a handheld games console ignoring the TV news.

Even Jimmy turns over his radio when the news comes on, he’d much rather hear the football. Jimmy’s father at one point finds Michael’s game after the bomb has hit, he cries deeply when reminded of his deceased son. But there is perhaps also another reason for his tears: It’s worthless, who needs entertainment when you can’t eat it.

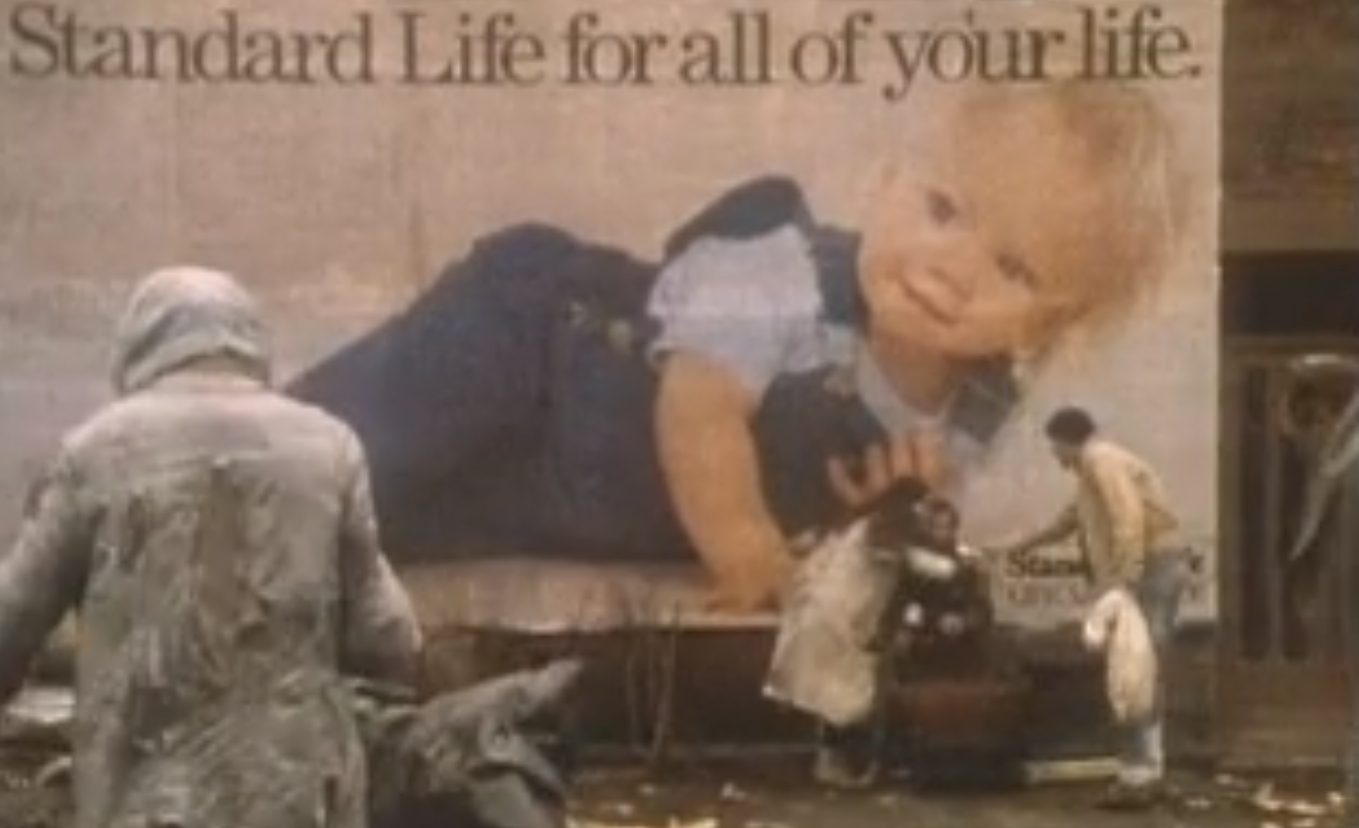

Food becomes something taken for granted before the bomb as Threads shows sequences where old women argue over a slight increase of an everyday item in a supermarket. This seems completely tenuous when later, Ruth and another survivor are forced to tear apart a dead frozen sheep. The film is full of slight ironies coming from advertisements and slogans for companies. Most notably is a sequence when in desperation Ruth has to eat a plastic bag full of dead rats which has gleefully printed on it: ‘‘Gateway Good food, right up your street”.

5. Allegory

When looking at Threads there is perhaps a question as to why in the film, it is the North of England that is bombed? In comparison to the country’s capital city of London, which would have had a more devastating effect. Sheffield being a large and industrious city of course makes sense strategically, but with the mass destruction a nuclear bomb has on a city, why wasn’t it sent to the country’s core?

Perhaps one has to look at the choice of setting somewhat allegorically. Aforementioned, Sheffield has always been seen as a city of industry with local coal mines as well as thriving steel production, giving it the nickname the ‘Steel city’. This, however was soon to be challenged by the Thatcher administration which began to close the pits and the factories as well as selling them off to private companies in order to create a more competitive labour market. As consequence to this, many people lost their jobs and in the U.K by 1982, 3,000,000 people were out of work, the first time since the 1930s.

We see the effect of this unemployment in Jimmy’s father who, from losing his job, is emasculated to a more traditional household role as he wears a floral pinny and cooks the family’s dinner. He spends his days at an allotment gardening which Jimmy shrugs off as unimportant. Come the bomb when gardening is actually needed, Jimmy’s father doesn’t attempt to assist and eventually dies seemingly unimportant despite his needed skills. Jimmy, also a manual worker is killed in the blast. The bomb is perhaps more political than it is nuclear, hitting at the time when industry was dying which, in turn, meant the city was too.

We also see this with the destruction of the council who attempts to run the city after the attack. They too eventually all die and the city is left without leadership, descending into further chaos. The Thatcher establishment began to roll back the necessity and power of local, and usually labour, county councils which in some cases were eventually abolished. Threads seems to be critical of this, which is shown when the council in the film are literally starved to death in an underground bunker trapped beneath a pile of rubble. The rubble being a metaphor for the crushing weight of the increasingly centralised government.

Conclusion:

Threads’ importance to cinema is its ability to harness the anxieties and political turmoil of ‘80s Britain, only to expand it to the universal anxiety of an atomic war. It perhaps lacks the aesthetic and emotional power of a film such as Alain Resnais’ Hiroshima, Mon Amour (1959) or even attempt the experimentation of form which we see in Watkin’s The War Game.

However, Threads captures the nuclear imagination in a bleak and potentially realistic way which we do not see in other dystopian nuclear films. Even with today’s less squeamish sensibilities the film manages to shock, scare and still remain current. This is especially poignant as some of the fears of the nuclear imagination have begun to rear their ugly heads once more.

Author Bio: Laurence Smither is an undergraduate at Royal Holloway University London while also a free-lance writer and reader. Interested in Literature, German New Wave and British Cinema, Laurence is currently writing his dissertation on the BBC’s Threads and The War Game.