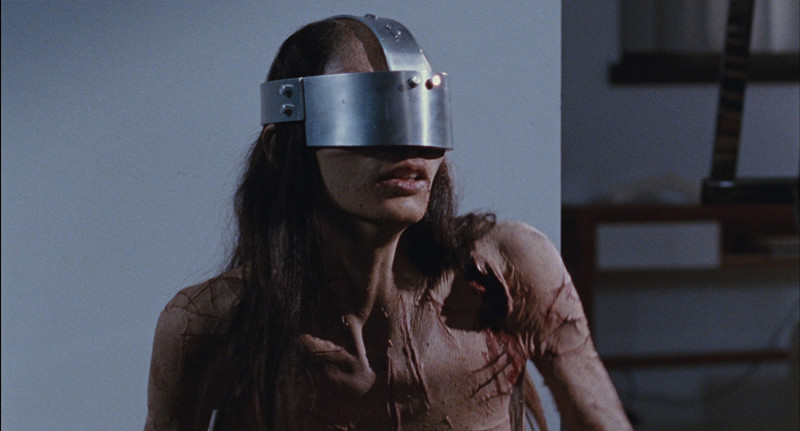

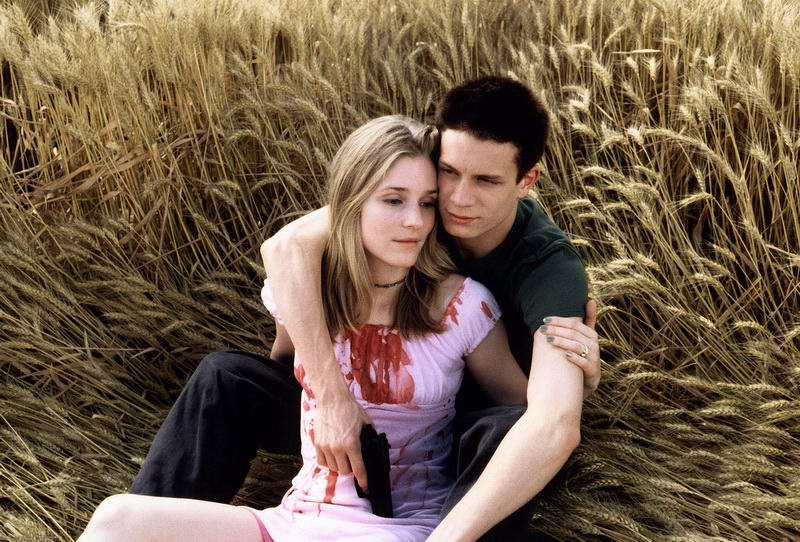

For about twenty years now several directors in and near France have been making some of the most formally interesting, thematically dark, and in many cases just plain difficult to watch films in the world. Together these films are known as the New French Extremity. They are challenging and often misunderstood.

There are other lists on this site that include or are devoted entirely to these films. The five ideas below, each central to the NFE, will cut deeply into these films and reveal the dark, glistening heart that beats within them.

1. NFE is one of the only (if not the only) readily definable cinematic movements currently producing films in the world today

What is a “cinematic movement” in the first place, and why should we care about such a thing?

Our starting point here will be Steven Soderbergh’s definition of “cinema” from his keynote at the 56th San Francisco International Film Festival: “Cinema is a specificity of vision. It’s an approach in which everything matters. It’s the polar opposite of generic or arbitrary and the result is as unique as a signature or a fingerprint. (…) It means that if this filmmaker didn’t do it, it either wouldn’t exist at all, or it wouldn’t exist in anything like this form.”

It’s rare enough these days to find individual directors making cinema by this definition. Even worse, long gone are the days of revered cinematic movements in which multiple directors were each striving for this “specificity of vision” Soderbergh describes. Such movements—from Italian neorealism (Rossellini, De Sica, …) and the French New Wave (Godard, Truffaut, …); to ones more loosely defined like New Hollywood (Cassavetes, Coppola, …); and even to ones named after many of their major works had already been created like Film Noir—are defined by common ideas and aesthetics as much as by the specific directors whose work falls within their boundaries. Directors who are commonly grouped into the NFE—much like those often grouped into the so-called American avant-garde (Deren, Brakhage, …)— produce their work separately and individually, but explore common thematic and aesthetic concerns.

In the vigorously, almost outlandishly derogatory Artforum by James Quandt in which he coins the term “New French Extremity,” he quotes director François Ozon as saying, “What I am interested in is violence and sex, because there is a real challenge in rendering the strong and powerful, as opposed to the weak and trivial. I like something that asks moral questions.” This quote well summarizes the movement, except that it leaves out the bluntness and, perhaps we could say, “flattened intensity” (which is rendered no less intense by this flattening) of the NFE.

In his diatribe, Quandt describes Claire Denis’ film Trouble Every Day as having a “shadow plot” that “is both cursory and ludicrous.” He’s not wrong either, and that description could similarly apply to any number of other NFE films. But his error is his incapacity to push past his derision to see the possibilities for real depth and beauty that can be opened in skilled hands by shadow plots that are both cursory and ludicrous.

A useful comparison can be made here to the harsh noise subgenre of experimental music, particularly considering that at least one NFE film is actually scored by musicians with decades of history working close to this subgenre (Philippe Grandrieux’s La Vie Nouvelle scored by Étant Donnés).

On the face of it, for example, pressing the blades of a metal fan against the strings of a guitar and setting those blades spinning is an act both cursory and ludicrous. However, in the hands of seminal harsh noise artist Boyd Rice (performing as NON) this so called roto-guitar generates a nuanced intensity of sound that is first brutally flat as it approaches white noise, then also somehow vibrantly alive in the hypnotic complexity of its deliberate cacophony.

Such transgressive provocation opens doors. The choice, then, is ours to step through with eyes and ears open to discover what lies in wait.

The call for papers for a conference titled “The New Extremism: Contemporary European Cinema” defines its longer, academicized revision of Quandt’s simpler term as, “[A] growing body of films featuring extreme and graphic representations of sexuality and violence, seemingly designed with the chief aim in mind of shocking or provoking spectators.”

Perhaps as years pass and the NFE gets more thoughtful attention because of its apparently steadfast refusal to disappear, even directors who disavow the NFE label will come to embrace it. More likely, however, they will continue to resist it.

2. NFE is a “Cinema of resistance,” not an “avant garde cinema”

Replacing the word “architecture” with the word “cinema” in a provocative passage from the late experimental architect Lebbeus Woods’ “Thoughts on Architecture of Resistance”:

“[Cinema] of resistance is different from avant-garde [cinema]. The avant-garde is just that: the vanguard of the majority, scouts leading the way for most people—those already in agreement—to follow. The avant-garde is a projection of the main tendencies in society, the values, practices, the aspirations of the majority, and cannot separate itself from them. The avant-garde is the mainstream, a manifestation of where it wants to go.

“[Cinema] of resistance is quite different. It does not believe in progress, that is, in the additive, cumulative, linear progression of history, or in the extension of a narrative of inevitability. Instead, it seeks to be effective in the present, for the sake of those who find themselves without a place to be themselves. This includes, among others, its [filmmakers], who resist received notions of what [cinema] is and does.

“[Cinema] of resistance begins with [a filmmaker] who resists.”

Immediately this definition of the avant garde is provides a powerful clue to the critical distaste the NFE has inspired. The avant garde presents positive and engaging challenges for critics to interpret as they lead audiences forward into an otherwise uncertain future. Resistance, on the other hand, is a less pleasant, less engaging element in the constellation of art-making and art-reception. Resistance, fundamentally, disengages—pushes back against engagement.

This idea of resistance explains, in part, NFE directors’ disavowal of the term with which they are lumped together. These are filmmakers who do not want to be categorized. They want each film to be taken on its own. They want the individual artistry of their work to be respected above casually being lumped in with others. This idea of resistance also opens up the horizon of the transgressions that NFE filmmakers make aesthetically, narratively, and in terms of the subjects they dwell on.

Here we see the embrace of representing:

a. Raw emotional expression, which as spectators we are neither carefully prepared for nor reassuringly debriefed from in the ways that traditional narratives take care of us as we absorb them.

b. Obscenity, as usefully (re)defined by French cultural critic Jean Baudrillard, here summarized by Paul A. Taylor in The Baudrillard Dictionary: “The obscene denotes much more than a simple moralistic condemnation. The prefix ob refers to the idea of hindering or being against. The ob-scene therefore expresses the collapse of distance in our social experience and the deleterious effect this has on our ability to experience reality in a non-mediated state.”

This ob-scene is thus wielded within NFE as a precisely calibrated tool. With it the filmmakers, in a sense, turn the aesthetic possibilities of film (the mediator of reality) against the medium itself to reinstall in us this lost sensitivity to and appreciation of non-mediated reality. In other words, NFE pits its perversions of the tools and traditions of mediation against mediation in the hope of creating a new kind of mediation that approaches the direct communication of raw experience.

At its best, this paradoxical battle with mediation is driven by resistance to:

a. Narrative complexity

b. Character depth

c. Visual determinacy

d. Standard cinematic codes of scene blocking, camera position, lighting, editing, etc.