3. Villeneuve continues Scott’s exploration of dream-like cinema

In one of the most entrancing scenes of the original “Blade Runner,” a dying man held a dove. It’s a strange moment—there was no hint as to where the angelic-looking bird came from—yet it made sense in the artistic terms set by the film. Whereas most mainstream movies present clean, clear narratives that audiences can easily absorb, “Blade Runner” strove to disorient viewers using surreal imagery, leisurely pacing, and hypnotic repetition, creating a cinematic dreamscape that its sequel expands.

For a filmmaker, one of the greatest advantages of this form of moviemaking (other superb twenty-first century examples of it include Dave McKean’s “MirrorMask” and Terrence Malick’s recent works) is that it frees directors from the shackles of realism. It doesn’t require a filmmaker to, say, abandon the laws of physics, but it does allow them to conjure up fanciful visions, like the pyramid from the first “Blade Runner” that was pierced by golden light.

That daunting edifice was the home of replicant creator Eldon Tyrell (Joe Turkel). His work has been repurposed by Wallace by the time “Blade Runner 2049” begins and fittingly, Wallace lords over a base of operations that mirrors Tyrell’s kingdom in its opulent strangeness. Inside, walls gleam like honey; rippling shadows are everywhere, as if the sun were shining into the building through a fish tank; and Wallace hides in the strangest of offices—a smooth platform situated in the middle of an indoor lake.

“Blade Runner 2049” features other haunting locations (including a scrapyard filled with unexplained dangers). Yet Wallace’s sinister and beautiful domain best fulfills the film’s aspiration to recreate the visual weirdness that the first movie achieved so brilliantly. Often, you may not know what exactly it is that you’re looking at, but you can’t look away either.

The second aspect of this sort of storytelling—molasses-like pacing—is one area where “2049” deepens its predecessor’s spell with the benefit of a height advantage. Unlike “Blade Runner,” which concluded in under two hours, “Blade Runner 2049” lasts a staggering two hours and 43 minutes. Being immersed in its bizarre worlds—like a room where a hologram of Elvis flickers on and off—for a much longer period of time has the powerful effect of leaving you dazed, but high on the rush of absorbing so many peculiar visions.

Many of which are recurring. Scott was fond of repeated images—the replicants’ glowing eyes, the iconic video billboard featuring the pill-popping geishas—and so is Villeneuve. That scene where Joi feels the rain on her skin, for instance, is echoed in a similar image of a snowflake landing on K’s hand. What’s more, the movie’s villains receive their own reverberations (after Wallace slaughters a replicant, he gives her an unholy smooch; mid-fight, Luv gives K the same treatment), giving the film the seductive force of a swinging pendulum.

There’s plenty of meaning to be found in this apparent madness. But as with the first “Blade Runner,” much of “2049” is pure, magical sensation that leaves you in withdrawal and craving more.

4. Together, K and Deckard present a complex portrayal of masculinity

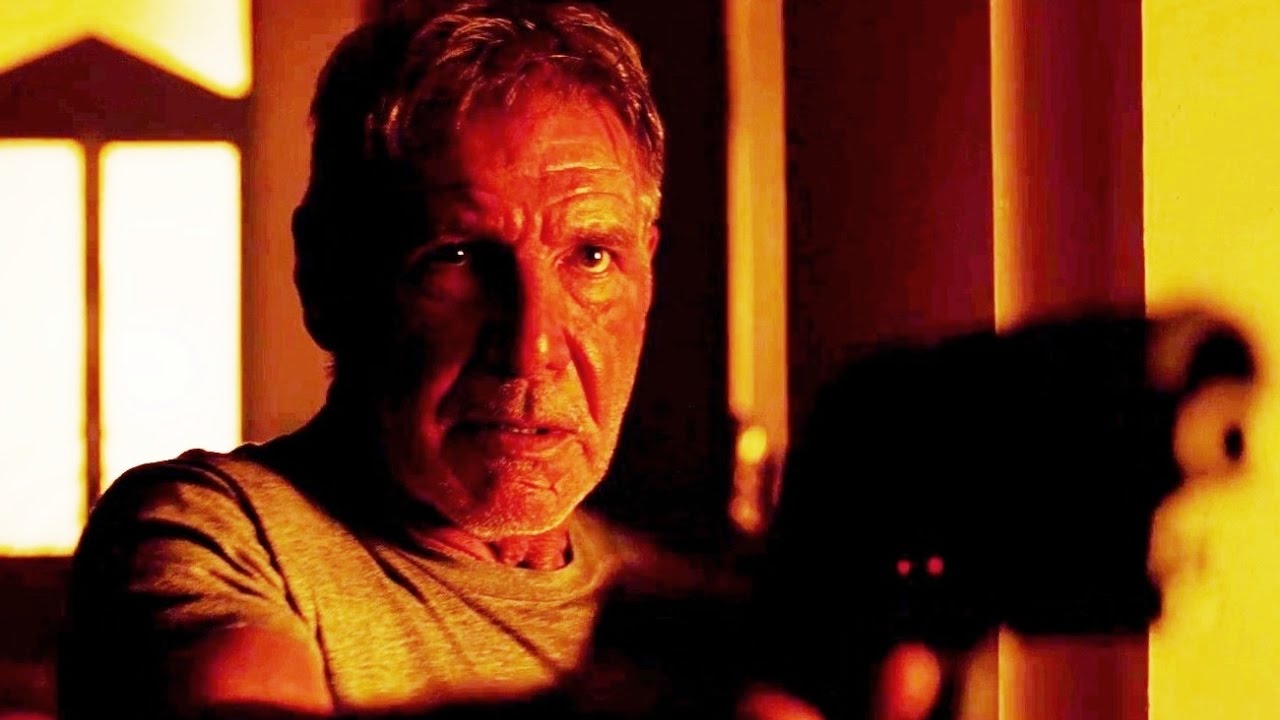

Villeneuve makes us wait, wait, wait for the movie’s meeting of blade runners future and past, stirring the suspense to near-Hitchcockian levels. Yet the fateful first encounter between K and Deckard (which takes place in a derelict Vegas casino) is meaningful for another reason: it offers a surprisingly nuanced portrait of masculinity. As K and Deckard, Gosling and Ford embody two male characters who are strong, honorable, and even willing to betray flashes of pain and sadness in front of one another. That may not sound like much, but in this brand of speculative cinema, it’s rare and it’s inspiring.

The first flickering of vulnerability arises as K grills Deckard over drinks. Why did Deckard leave his child behind? What was his lover’s name? “Too many questions,” Deckard growls. Yet it doesn’t take long for you to feel the regret he feels for his lost life and love—and K’s desperation to learn about his family. Until now, both men have mostly kept up stoic fronts; now, the macho posturing begins to peel away.

In its place, something more complex blossoms. While K doesn’t tell Deckard that he suspects he’s his son, he’s obviously enraged at the idea that me might have been abandoned by his father. Yet he goes silent when Deckard explains that he wanted the child hidden away because he was being hunted and didn’t want his offspring to be “taken apart” and “dissected.” “Sometimes, to love someone, you got to be a stranger,” Deckard tells K. It’s a cool line, but it’s more than that—it’s an older man outlining a code of honor to a younger man who needs to learn to look beyond his own desires.

K takes Deckard’s words to heart and a powerful love forms between them. The film’s watery climax features K saving Deckard (rather than a screaming damsel in distress) and an early tête-à-tête between the two men is interrupted by Elvis crooning, “Can’t Help Falling In Love.” Theirs is a moving bond that recalls some of the most potent depictions of male friendship in sci-fi, including Ford’s heartfelt bromance with Mark Hamill in the original “Star Wars” trilogy (their lack of shared screen time in “The Force Awakens” still fills this critic fandroid fury).

Unfortunately, “Blade Runner 2049” falls into the same trap as “Star Wars”: the white trap. As admirably diverse as Villeneuve’s cast is (it includes actors from Cuba, Iceland, and Israel), the film is still about two white guys and their white-guy issues. And while Gosling is a wonderfully sensitive K, it’s hard not to imagine what a different, radical movie “2049” might have been if Barkhad Abdi—the Somali-American Oscar nominee from “Captain Phillips,” who shows up for one scene here—had anchored the film.

Therein lies the crack in the movie’s progressive bona fides. It effectively preaches tolerance, but marginalizes the people who face a similar kind of bigotry in 2017 that the replicants face in 2049.

5. A revision of the sci-fi savior narrative

From Neo to Rey, sci-fi films are packed with saviors. They tend to come from nothing—a bland office, a barren planet—but inevitably, they all have a grand destiny and a great head of hair. They fuel our daydreams of accomplishing great and important deeds, even if their adventures subject them to Christ-lite suffering.

But those fantasies have no place in “Blade Runner 2049.” While the film features a “chosen one” of sorts, it isn’t K and it isn’t Deckard. Thus, the film becomes a paean to heroes who may not be icons or saints, but refuse to let that stop them from (to quote Daenerys Targaryen, one of pop culture’s most fascinating and ambiguous savior characters) leaving the world better than they found it.

That idea bubbles into the narrative after Luv viciously attacks K and captures Deckard (so Wallace can interrogate him about the child). K survives, but only because Freysa’s forces rescue him. They bind his wounds and spirit him away to their stronghold, but the encounter leaves K weaker than he was before. Why? Because Freysa reveals to him that which he refused to consider: that he is not Deckard and Rachel’s son, but just one of the many assembly line replicants. “You imagined it was you,” she says pityingly, then adds, “We all wish it was us.”

Robbed of the one thing that made him feel as if there was a real heart beating in his tin body, a despondent K wanders the city. But then he remembers something else that Freysa said: “Dying for the right cause is the most human thing we can do.” So he races after Deckard and Luv, forcing them to land outside the dark, towering wall that keeps the sea from pouring into the city. The following fight leaves K mortally wounded, but he manages the drown Luv, surviving just long enough to lead Deckard to his actual child (whose identity K finally uncovers during the film’s last act).

The last time we see K, he’s lying on a snowy staircase and has passed into the void. Yet it’s hard to feel too saddened by his death. After all, he did what he had to do. He was not human, but he was something better: a good man.

Author bio: Bennett Campbell Ferguson is a freelance film critic and culture writer based in Portland, Oregon. In addition to reviewing films for Willamette Week, he founded the blog T.H.O. Movie Reviews, which he also edits.