Kinji Fukasaku’s last film was a production worthy of his lifetime achievements in the field, since “Battle Royale” caused much controversy; it was banned outright or deliberately excluded from distribution in several countries, but at the same time, it also influenced a great number of movies and many filmmakers, including Quentin Tarantino and “The Hunger Games”.

Here are seven reasons why the film is considered a cult masterpiece. Please note that the article contains many spoilers.

1. A great adaptation of a truly inspired novel

At the beginning of the new millennium, unemployment has reached 15 percent with 10 million people left without a job, while school violence has reached unprecedented levels. In order to control the youth, the desperate government votes in the ‘Battle Royale’ law, which states that each year, students from a randomly chosen class will be transferred to a secluded island where they will have to fight to the death, to the last person standing.

The story, which is based upon the homonymous novel by Takami Koushun, revolves around the most recent chosen class. The main characters are Kitano, a former teacher at the class’s school, who resigned after being attacked by a student and is now the ‘host’ of the ‘game’; Shuya Nahara, a middle school student who tries to cope with his father’s suicide; Noriko Nakagawa, whom Shuya swears to protect during the battle; and Kazuo Kiriyama, a transfer student who emerges as the most dangerous individual of them all. Mitsuko Souma and Takako Chigusa are eventually revealed as the most bloodthirsty among the girls. Also, Shinji Mimura is a computer expert who plans to hack the army’s computer.

What ensues is a bloodbath where every student’s true nature is revealed, and compassion and friendship seem to have disappeared. Action, killings, suicides, shifting loyalties, and the almost constant threat of death hanging over everyone’s heads comprise a truly dark setting, the place in which the story takes place.

2. A definite cult film

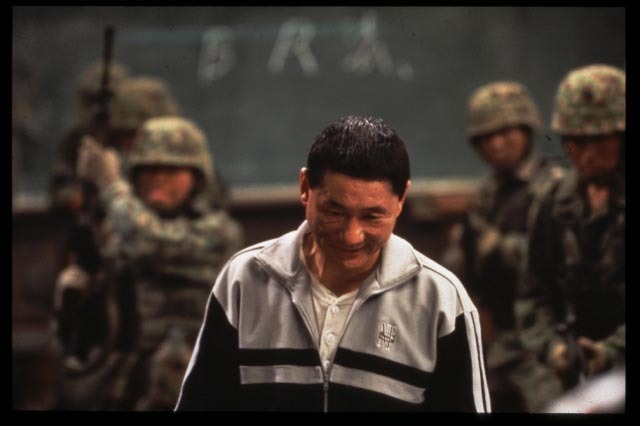

“Battle Royale” is one of the most definite cult of films of Japanese cinema for a number of reasons. It was Kinji Fukasaku’s last film; he’s known as one of Japan’s most cult filmmakers, particularly due to his “Yakuza Papers” pentalogy. Takeshi Kitano’s presence, which is usually enough by itself to give the title cult to a film, is also especially relevant here. The exploitation aesthetics and the humor that comes at the most unexpected moments are also distinct cult indications.

The fact that Tarantino was evidently inspired by this film, even casting Chiaki Kuriyama in “Kill Bill” as Gogo, makes it an undeniably cult film. In my opinion, Kuriyama, along with Eihi Shiina, are the most cult contemporary actresses in Japan. The concept of the tournament is usually a cult indicator, as in films like “Master of the Flying Guillotine” or even “Bloodsport”.

3. Kinji Fukasaku uses violence to portray his sociopolitical comments

The film proves, once more, the dichotomy of Japanese society. The Japanese are actually conservative, but at the same time have a deep inclination toward the extreme, which they try to keep hidden, frequently hypocritically. The fact that so many extreme adult films are produced in the country, but with authorities insisting on blurring out body parts, even in nude photography, is a clear indication.

In that fashion, the official approach toward the film from the country’s National Diet was to condemn it, while the audience made it into one of the most commercially successful Japanese films of all time. Both policies occur due to the violence depicted in the film.

Accordingly, the graphic depiction of savagery is nothing new in Japanese cinema, as violence among kids has been presented a number of times before; for example, as in “Emperor Tomato Ketchup”, which is even more grotesque in its presentation. Furthermore, Fukasaku’s films always entailed many violent scenes, and “Battle Royale” simply follows in the steps of movies like the ones comprising “The Yakuza Papers Collection”.

The protagonists of “Battle Royale” are 15-year-old students; Fukasaku, at that age, was working in a factory during World War II, which was a regular target for Allied bombing raids.

Due to that fact, violence against and from children of this age is not so shocking to him. I think the same applies to the Japanese audience, particularly the ones who experienced the war directly or indirectly, while the ones who were actually shocked by the film were mostly Westerners. The cult audience, though, could not help but adore it.

Fukasaku’s experiences in the war also made him realize the lies the Japanese government told the people during those years, and subsequently made him hate the government and politicians. This sentiment is portrayed here eloquently, as politicians are the ones who actually instigate these fights to the death among the students.

The criticism of the fierce competition of the Japanese educational system is also criticized, as is school violence, and the disparity that was instigated during the 90’s crash. Fukasaku took all of the psychological violence existing in the school environment and transformed it into actual brutal episodes among teenagers, who become cold-blooded killers much more easily than even they could fathom.

4. Impressive acting in cult fashion

Roughly 6,000 actors auditioned for the film, which was narrowed down to 800 potential cast members. These finalists were subjected to a 6-month period of physical fitness training under supervision of the director, Kinji Fukasaku, who eventually cast 42 out of the 800.

Aki Maeda, who played Noriko, was actually 15 years old during the shooting of the film. Her performance paved the way for her future career. The same applied to Tatsuya Fujiwara who played Shota, although his hyperbolic acting began in this film and never actually ceased.

The ones who steal the show, however, are not the aforementioned protagonists, but the secondary characters. Apart from Takeshi Kitano, who plays Kitano in his distinct style of laconic violence, three other actors retain the cult element in the film. Chiaki Kuriyama as Takako Chigusa and Kou Shibasaki as Mitsuko Souma make spectacular villains, in two very violent performances that eventually led the first to play Gogo in “Kill Bill” .

The third is Masanobu Ando who plays Kazuo Kiriyama, another truly sociopathic villain with an evil coolness that definitely stands out.

5. The “Death of the Teacher” scene

In a scene that synopsizes the ironic aesthetics of the film, Shuya shoots Kitano after he threatens to shoot Noriko. As he falls, Kitano shoots, revealing the gun to be a water gun. As he lies dead, his cell phone rings. He then picks it up and when he realizes it is his daughter, he angrily rebukes her before he dies once more.

This may be a minor scene, but the preposterousness of it and the fact that it has nothing to do with the permeating violence and drama of the film is bound to make anyone who watches it laugh. The scene is a prominent example of the dark and absurd sense of humor the Japanese people have, in a style that frequently appears in Kitano films.

6. A soundtrack that emphasizes the concept of the film

The film score of “Battle Royale” was composed, arranged, and conducted by Masamichi Amano, performed by the Warsaw Philharmonic Orchestra, and features several pieces of Western classical music along with Amano’s original compositions.

Music in the film is almost constant, as it is played over the PA system and heard all over the island. The use of classical music, however, serves another purpose. It sets the tone of the film, as it emphasizes the fact that the action is framed according to the wishes of the previous generation. In that fashion, it highlights the fact that the students are actually pawns in a sick game that exists solely for the entertainment of adults.

Furthermore, it reminds the viewer that, despite the fact that the ones killing each other are students, the real villains are the adults, who have orchestrated this whole concept.

7. Cinematography combining beauty with gore

Katsumi Yanagishima tried to give the film a game show feel, although this game’s focus is death. The remote island provided a great setting for this feel, both in the forest and in the various abandoned buildings, where the claustrophobic sentiment permeating the film seems to be at its strongest.

However, he also focused on the beauty of the place, particularly through the vast grasslands that offer a number of impressive images. This aspect finds its apogee in an image of the lighthouse, where the sun is barely coming out of the cloudy weather, creating a truly impressive canvas, particularly through the meaningful shadows.

Author Bio: Panos Kotzathanasis is a film critic who focuses on the cinema of East Asia. He enjoys films from all genres, although he is a big fan of exploitation. You can follow him on Facebook or Twitter.