It’s 1996. Stanley Kubrick has been discussing a project with global superstar Tom Cruise for well over a year. This discussion also entails Kubrick demanding tapes of the work of actress Nicole Kidman who was, at the time, Cruise’s wife. This project has been gestating and forming shape in Kubrick’s head for some three decades.

It’s based on Arthur Schnitzler’s “Traumnovella”, a book originally published in 1926 and focusing on exploring the themes of intimacy, sexuality and envy through the story of a 35-year-old doctor and his wife who live with their daughter in early 19th Century Vienna.

Kubrick then decides to notify Kidman of their intentions and faxes over a copy of the script to both actors to read. Cut to a few months later, and Kidman and Cruise are in England prepared to stay for as long as required and throw themselves into anything the auteur asks of them.

It would turn out to be a long production, one that holds the Guinness World Record for the longest continuous film shoot of 400 days. Rumors of the cinematic genius, who had already been labeled as “eccentric”, “reclusive” and even “deviant” by the speculative media who never got access to him, exploiting the two superstars at his command began spreading. Very swiftly this secret, expansive feature began to create a frenzy all over the globe. The fact that Kubrick had not made a film in 17 years certainly helped it to a great degree.

In 1999, a week after Kubrick had shown a finished cut of the film to the executives at Warner Bros. as well as Kidman and Cruise, he passed away. The filmmaker’s unimpeachable legacy fueled the anticipation of the film, as did the fact that he considered the film to be his greatest contribution to the art of cinema. Most of Kubrick’s films had a distribution and promotion strategy designed and controlled by the man himself.

With that task now in the hands of Warner Bros, “Eyes Wide Shut” was set up for disappointment. They sold a lot of tickets, thanks to their misleading trailer and unnecessary “sanitization” of some of the explicit scenes of the film with unbearably ludicrous graphics that made sure they got an R rating, but while the film rendered serious film fans perplexed, mainstream audiences dismissed the film’s experimental pacing and lack of eroticism completely. It was touted by the media before its release as the sexiest film ever made, and what was on the screen was anything but titillating.

Astonishingly misunderstood at the time by most critics and audiences, “Eyes Wide Shut” is still never counted among the director’s most accomplished triumphs, even after going through the trajectory all Kubrick films post- “Lolita” did, which basically involved a mixed reception at the film’s opening and being anointed a classic some ten years down the road.

So here are 7 reasons why the film deserves to be reassessed and seen among Kubrick’s most towering achievements.

1. Timelessness of the Story

At the time of the film’s release, as a member of a critics’ panel assembled by television host Charlie Rose for a discussion on the film and a definitive dissection of Kubrick’s legacy, David Denby of ‘The New Yorker’ pointed out that Schntizler’s novella, published in 1926 and set even earlier, doesn’t lend itself to adaptation in a modern setting. As per him, the story worked in the time of Freud’s work on dreams and fantasies and the explosion of female eroticism in Viennese paintings. But transported to modern-day New York, it felt incredibly dated.

That is where Kubrick’s intensity in delving into the psychology of the character of Bill Harford (lovingly named after Harrison Ford, whose on-screen persona Kubrick believed to be the perfect archetype for the character of Bill) comes into play.

Early into the film, in a subtly composed scene, we see Bill greeting an old friend of his from college at the Zeigler’s Christmas party where the friend is playing piano with the band. From their awkward, overtly saccharine interaction, it is easily discernible how much Dr. Harford has presumed his own superiority over his friend who dropped out of medical school. “You haven’t changed a bit.”, he casually remarks, Cruise’s body language oozing a deliciously naïve assuredness.

Thus, when Alice, in what can be interpreted as an act of protest in response to their increasingly sedate existence, shatters every assumption Bill has ever had of what their relationship entails, it feels incredibly, threateningly close to life.

On paper, Bill’s inherent disbelief on discovering his wife’s darkest fantasies in a scene that in its adaptation from the novella has been left completely intact, might seem ridiculous for a man we expect to be highly progressive. But translated to film, it is so audaciously effective, in part due to Kidman’s haunting vulnerability and in part due to how endangered Bill’s very being feels.

What follows this conversation is such a deeply humanistic expression of deep-rooted, bleak envy that all question of the urgency of the narrative are put to bed. As with most Kubrick films, logic dissolves, and if you give the film the authority to sink its teeth into you, the experience alone informs you of its perennial relevance.

2. Use of Music

“Eyes Wide Shut” begins and ends with Dmitri Shostakovich’s “Waltz No.2” that serves different purposes each time it gracefully envelopes the film. In the opening, it acquaints us with the rosy existence Bill and Alice have in their large New York apartment, with seemingly no irregularities to discomfort them. But there also exists a tangible mundanity that pulsates beneath the surface, threatening to tear everything apart if it made its presence known. It also helps to distance the audience from the characters and the setting, elegantly making them voyeurs to the experience, just like Bill is in all his adventures.

In the closing credits though, the effect is much more cynical and sharp as compared to the sweeping transcendence the notes cause in the beginning and in the sequence where we see Bill and Alice going about their day. It is driving in, with an ambrosial quality, the irony of the narrative. We see Bill and Alice wake from their long, blissful slumber and confront their reality, but even the wisdom gained from their experiences cannot possibly last forever.

Among other brilliant employment of classical musical pieces in the film is the second movement of György Ligeti’s piano cycle “Musica ricercata”. Ligeti’s music is gratifyingly hypnotic in the film; fueling the surrealism of Bill’s situation.

As per the legendary composer, he wrote the piece when he lived in Hungary, as a metaphorical knife in Stalin’s heart. Emphasizing how rudely awakened Bill Harford feels, Kubrick makes the unforgiving music breathe a foreboding, nightmarish quality to the proceedings. It’s nowhere near the use of Ligeti in “2001: A Space Odyssey”, but it lingers in your head long after; Bill’s predicament making you constantly aware of the film’s intentions as we unravel each ambiguous layer.

Of course, Jocelyn Pook’s atmospheric score isn’t entirely without merit. Its vivid, erotic sensibilities blended into Kidman’s whispered revelations about the Naval Officer are indescribably rousing and haunting.

3. Cinematography

Even the most ardent Kubrick detractors cannot claim to have not been won over by the visual bravura of his work. His background in photography enabled him to foresee the importance an image can hold in the memory of the viewer, and if judged purely on an experiential basis, memory is the only thing that ensures the temporal relevance of a film.

Subsequently, he changed cinema with his ingenious use of practical effects in “2001”, the electrifying dizziness caused by the distorted frames of “A Clockwork Orange”, the stately use of natural light in “Barry Lyndon” and even the mellowed colors of “The Shining”, that boldly contrasted with the dark themes of the film.

In “Eyes Wide Shut”, Kubrick, with DP Larry Smith, captures the grandeur of high-society New York life wrapped in starkly bright Christmas lighting used to impeccable and darkly comic effect. Families get closer during the holidays, celebrating the intimacy they share which invariably is the point of a life like the one Bill and Alice seem to lead. But Bill’s world has been turned upside down, and he is veering away from what on the surface is a closely-knit household, all the time being surrounded by the glaring crimson of these lights, heightened by the beautiful camera work.

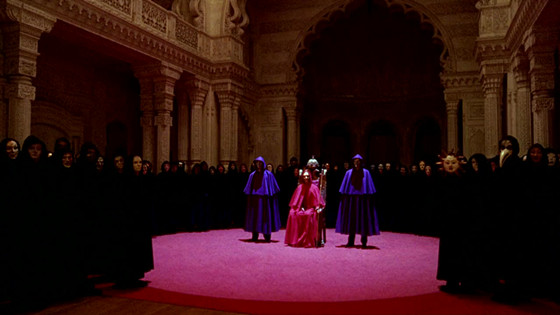

One of the most memorable visual work in “Eyes Wide Shut” is the exquisitely mounted Christmas party at the house of Victor Ziegler, one of Bill’s wealthy patients.

While Bill is called upstairs to tend to a prostitute who has overdosed in Ziegler’s bathroom, Alice is seduced by a man named Sandor Szavost, who senses a longing in Alice’s eyes and attempts to exploit it. And as we see them dancing, enveloped in this beautifully old-fashioned lighting and as Kidman’s quietly tragic words leave you utterly dumbfounded, the film has gleefully seduced you into its singularly odd look and feel.