In the macabre and entrancing first scene of Frank Miller and Robert Rodriguez’s “Sin City,” a woman in a scarlet evening dress (Marley Shelton) and a man in a black business suit (Josh Hartnett) chat on a massive balcony overlooking a vast and shadowy metropolis. It’s a gushingly romantic encounter and for a moment, you think it might be the beginning of a long night—until you hear the soft “thwack!” of the man’s silencer-muffled gun and the woman falls dead in his arms.

That’s how Miller and Rodriguez welcome us to the terrifying world their film inhabits, a blackened void where love and mercy are rationed stingily and cruelty is the ultimate currency. “Sin City” may have plucked a disparate array of loners and losers from Miller’s graphic novel series of the same name, but those characters are united because they all exist in the same black-and-white urban hellscape, where the motives of even the most righteous men are tinged with leering barbarity.

When “Sin City” was released on April Fool’s day in 2005, that hellscape seemed like the talk of the moviegoing town—the film received largely rhapsodic reviews and ultimately grossed over $158 million worldwide.

Yet its sequel, “Sin City: A Dame to Kill For,” arrived in the summer of 2014 with a whimper, selling only about a quarter the amount of tickets its predecessor sold and drawing sneers from reviewers (“Rare indeed,” wrote Variety’s Justin Chang, “is the movie that features this many bared breasts, pummeled crotches, and severed noggins and still leaves you checking your watch every 10 minutes”).

Still, despite the staleness of its successor, the original “Sin City” (which is intensely faithful to its source material) remains a richly enjoyable and fascinatingly lurid chapter in the history of neo-noir films. So grab a pistol, a trenchcoat, and a set of Venetian blinds. We’re going back to Miller and Rodriguez’s first team effort to explore why it’s a neo-noir classic and why, despite its nauseating violence, it’s so difficult to resist.

1. It masterfully uses anthology-style storytelling

Taken at face value,“Sin City”—which adapts several volumes of the series—sounds like a gambit to cram as much Miller material as possible into a fan-friendly two hours. Yet the anthologized narrative structure of the film is actually a core tenet of its appeal, partly because when joined together, the stories of the three graphic novels that Miller and Rodriguez chose to adapt—“The Hard Goodbye,” “The Big Fat Kill,” and “That Yellow Bastard”—chart a three-act metaphor for the growth of the human spirit that spans the (relative) simplicity of childhood; the vexing complexities and occasional drudgery of adulthood; and the mournfulness and isolation that can come with old age.

That journey is kicked off by Marv (Mickey Rourke), a gruff, granite-faced thug hunting for the man who murdered his beloved Goldie (Jaime King). Like seemingly everything in Sin City, this quest mainly involves murder and torture, though it also serves as the movie’s “childhood” phase, since Marv’s juvenile worldview makes him seem like a figure in a unusually bloody medieval bedtime story. That, at least, is what Dwight McCarthy (Clive Owen) seems to suggest when he says that Marv “had the rotten luck of being born in the wrong century. He’d be right at home on some ancient battlefield, swinging an ax into somebody’s face.”

Dwight, whose brooding presence anchors the film’s second act, turns out to be a far different creature of the night. Ostensibly, his purpose is to protect the women who rule Sin City’s red-light Old Town district after the death of a scuzzy cop threatens their truce with the police. But whereas Marv’s gaze rarely extends beyond the horizon of vengeance, Dwight becomes mired in the intricacies of a corrupt law-enforcement system and faces some fairly mundane obstacles, including an empty tank of gas and a cop who stops him on a highway for “driving with a busted tail light.”

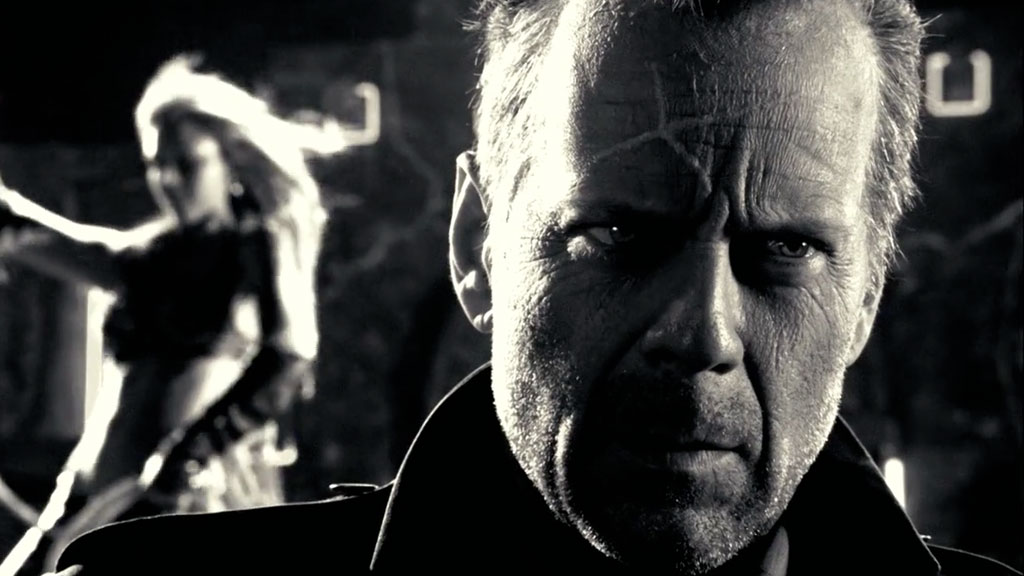

Dwight’s adventures, in other words, are a more grown-up version of Marv’s, just as the trials of noble ex-cop John Hartigan (Bruce Willis) in the film’s final act represent an evolution beyond Dwight’s experiences. That’s mainly because Hartigan bears more vestiges of age than his immediate predecessors (he’s a self-described “old man”), although that doesn’t stop him from intervening when a stripper named Nancy (Jessica Alba) is menaced by the Yellow Bastard (Nick Stahl), a pedophile with lemon-colored flesh who Hartigan rescued Nancy from when she was 11.

This queasily frightening tale is easily the most intimate story in “Sin City”—at times, it feels like Hartigan, Nancy, and the Yellow Bastard are trapped inside a morbid chamber play, which is fitting. Hartigan’s battered body has only so many breaths remaining, so the romanticism and layered scheming of the film’s first two thirds hold little interest for him—he just wants to save Nancy in what little time he has left.

At the end of the film, Hartigan smashes the Yellow Bastard’s skull (but only after ripping off his genitals), enraging the predator’s senator father (Powers Boothe). Then, hoping to avoid tempting the senator to target Nancy, Hartigan shoots himself, declaring, “An old man dies. A young woman lives. Fair trade.” It’s a blunt, powerful statement, and it effectively concludes the story of the movie’s three protagonists, who in a way seem like fractions of a single being at different ages.

2. It features stunning visual effects

Is “Sin City” an animated film? Not entirely, since it isn’t pure CGI (and doesn’t feature a chattering cowboy or clownfish). Yet the movie does belong to the same subgenre as “Avatar”—the wealth of films that rely on animated backdrops, but deploy flesh-and-blood actors and enough photographic realism that they can almost pass for live action. It’s an interesting sect of cinema, albeit one that too often relies on frictionless, airless landscapes that recall sour memories of the “Star Wars” prequels.

Nevertheless, “Sin City” is that rare movie that traffics in fakery and generates vitality, which is partly thanks to the vibrancy of its well-chosen flashes of color. While Miller’s books deviate from black-and-white imagery only sparingly, the film is full of moments that eerily echo the awful fate of the girl in the red coat in “Schinder’s List,” including a scene when a woman’s emerald eyes shine through the gloom of nighttime and a shot when the night sky turns crimson just before a storm of bullets is unleashed.

These fanciful flourishes are thrilling in their strangeness, especially when combined with the movie’s gorgeously computer-generated “sets,” which allow Miller and Rodriguez to revel in the otherworldly look of CGI. Thus, when Marv leaps through a window and plunges downward, the animated video-game-style rush of the ground surging toward him has a surrealistic vibe that, far from leaving you feeling cheated out of a real experience, makes the movie feel ecstatically alive.

3. It offers a fascinatingly bleak perspective on humanity

In one of the most exuberantly brutal scenes in “Sin City,” Dwight, Gail, and a few other Old Town women mow down a gaggle of hapless criminals with a hail of gunfire. It’s not a noble fight—cornered and unprepared, the criminals never have a chance of winning—but the cruelty of the massacre doesn’t bother Dwight and Gail, who pull their respective triggers with relish and cap off the killing with a swoon-worthy smooch.

By that point in the film, there’s been enough bloodshed that it’s pretty hard to be shocked by the image of a character savoring “the pure hateful bloodthirsty joy of the slaughter” (as Dwight puts it). What is shocking about “Sin City” is that in addition to being monumentally gory, it plays out in a moral vacuum where everyone (not just grotesque creeps like the Yellow Bastard) is tinged with depravity, including “good” people like Dwight and Gail.

Nowhere is this clearer than in the scenes featuring Hartigan, whose protection of Nancy has a predatory aura. He may growl, “No, Nancy!” when she attempts to reward his chivalry with a kiss, but it doesn’t take long for him to relent and dub her “the love of my life.” And while their relationship is clearly consensual, it’s creepy to watch Hartigan fall for the now-19-year-old Nancy, especially since it looks an awful lot like he’s taking advantage of her gratitude.

Whether or not Miller and Rodriguez fully comprehend the ugliness this narrative is up for debate, although it does seem as if “Sin City” is their attempt to parody the numerous misogynistic tales of male comic-book heroes stoking their egos by defending helpless women. That’s why it’s hard to believe Marv when he says, “It really gets my goat when guys rough up dames,” a declaration that the movie undermines by including a scene where Marv knocks a woman unconscious by smacking her across the face.

4. It contains some terrific black comedy

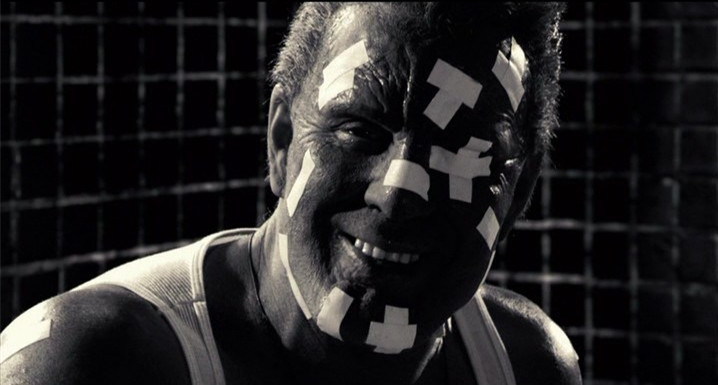

When a director mixes jokes with splatters of blood, they risk putting audiences in the uncomfortable position of feeling like they’re being hectored to laugh when they just want to vomit. Yet when Miller and Rodriguez took that risk in “Sin City,” it paid off thanks to their nimble navigation of the thin line between buffoonery and horror—and thanks to Jackie Boy, a mumbling, greasy-haired cop played with savage wit by Benecio del Toro.

Even by Sin City standards, Jackie Boy is pretty repulsive, not least because he terrorizes Dwight’s girlfriend Shellie (Brittany Murphy) and stalks one of the Old Town girls in his car. But even though Jackie Boy’s behavior is consistently disgusting, Miller and Rodriguez lift the mood by subjecting the character to an escalating series of comically over-the-top punishments, which include Jackie Boy’s head getting dunked in a toilet and later being severed and stuffed with a bomb.

Alone, these torments would be skin-crawling; strung together, their exaggerated awfulness becomes uproarious, keeping “Sin City” afloat when its grimness threatens to overwhelm. Thankfully, that spirit flows throughout the film and even extends to Marv, who, after a blast from an electric chair fails to fell him, cracks a dark joke: “Is that the best you pansies can do?”

5. It offers a compelling revision of classic film noir themes

Philip Marlowe may have never amputated the arms, legs, and head of a serial killer, but he still has a lot in common with Marv (and many more of Sin City’s shady residents). That’s because Miller and Rodriguez used the film to pay homage to film noir, thereby creating a vibrant revision of one of the most influential forms of cinematic storytelling.

Of course, “Sin City” is not necessarily a true noir—it has been argued that only movies made up to the late 1950s can claim that label, that film noir “consists of a finite group of motion pictures made during a specific historical period that share certain aesthetic traits and thematic concerns” (as John Belton puts it in American Cinema/American Culture). Still, many themes from the classic noir period that Belton mentions will sound familiar to “Sin City” devotees.

“Thematically,” Belton writes, “film noir grapples, as Robert Porfirio suggests, with existential issues such as the futility of individual action; the alienation, loneliness, and isolation of the individual in industrialized, mass society; the problematic choice between being and nothingness; the absurdity, meaninglessness, and purposelessness of life; and the arbitrariness of social justice, which results in individual despair, leading to chaos, violence, and paranoia.”

With minimal exceptions, those themes resurface in “Sin City.” Marv’s trip to the electric chair and Hartigan’s suicide do indeed hint at “the futility of individual action”; the plights of multiple characters in the film offer a crash course in industrial isolation; and the movie certainly doesn’t lack for chaos, violence, or paranoia.

Nevertheless, “Sin City” also offers a canny revision of some of the themes Belton describes. Film noir may explore “the arbitrariness of social justice,” but “Sin City” suggests that social justice is not only not arbitrary, but is in fact quite achievable. After all, Marv and Hartigan may not survive the film, but they do fulfill their quests to protect their respective paramours.

And as for the film’s most troubling loose end—the survival of Senator Roark, the Yellow Bastard’s father and Hartigan’s nemesis—it eventually gets tied off in “A Dame to Kill For,” when Nancy shoots Roark and declares, with typical Sin City gusto, “This is for John Hartigan, fucker.”

6. The beginning and ending scenes with Josh Hartnett deepen the film’s significance

Is Josh Harnett still a “Magic Man”? Not really; it’s been almost 17 years since he strutted down a high school hallway to the beat of that delectably gooey song from Heart in Sofia Coppola’s “The Virgin Suicides.” Besides, in the years since, his resume has become littered with bombs like “Hollywood Homicide” and “The Black Dahlia.”

Still, the post-”The Faculty” reunion between Rodriguez and Harnett in “Sin City” is one of the movie’s highlights. Not only does Harnett’s performance as the unnamed murderer in the film’s opening scene (which is based on “The Customer is Always Right,” a shorter Miller tale) ooze stoic and sinister charisma, but Miller and Rodriguez’s decision to deploy him solely at the beginning and the ending of the movie envelopes its narrative with terrifying symmetry.

Intriguingly, Harnett’s character (who is referred to in the end credits simply as “The Man”) is almost entirely disconnected from the rest of the movie. Marv, Dwight, and Hartigan may all pass through the same grungy bar, but “The Man” is kept at a distance—after he shoots the woman in the red dress, he doesn’t reappear until the last scene, when he smilingly offers the Old Town prostitute Becky (Alexis Bledel) a cigarette in a hospital elevator.

While The Man’s identity is never clarified, he is clearly an assassin (it’s implied that Becky is his next victim) and by bringing him in for one last kill, Miller and Rodriguez bring their narrative full circle. They also suggest that unlike most of the movie’s characters, The Man isn’t necessarily entwined in some sweeping conspiracy—he may just be one of many monsters in a monstrous realm, and further proof that in Sin City, evil is less an aberration than a way of life.

7. Alexis Bledel’s Becky shows the power of counterintuitive casting

Blue-eyed and sweet-voiced, Becky seems like the epitome of innocence. She’s more than that, though—she’s also the best-performed character in the film, which is saying something, considering that Bledel had to compete with the grimy wattage of Mickey Rourke’s mean grin and the deadly cool emanating from underneath Clive Owen’s dashing bangs.

“Sin City” makes it clear that Becky is not to be underestimated in her first major scene, in which a drunken Jackie Boy tries to coax her into his car. “Aw sugar, you just gone and done the dumbest thing in your whole life,” Becky coos when Jackie Boy draws his pistol. And she’s right: Soon, Old Town’s resident assassin, Miho (Devon Aoki), descends from the darkened heavens above to relieve Jackie Boy of both his hand and his life.

Of course in her own way, Becky is as much of a villain as Jackie Boy—as is turns out, she’s a spy in cahoots with Manute (Michael Clarke Duncan), a thug who (bizarrely) dresses a bit like a bellboy and dreams of bringing Old Town under the fist of his unnamed “master.” It’s a betrayal that enrages Gail, who retaliates by biting off a chunk of Becky’s neck.

You can practically feel Miller and Rodriguez grooving to the incongruity of that nastiness (did they watch Bledel on “Gilmore Girls” and wonder, “What if Lorelei bit Rory….?”). Still, it’s hard not to mourn Becky during her sure-to-be-fatal encounter with The Man. Becky may have betrayed Gail and the other women of Old Town, but as she hangs up her cellphone (“Love you too, mom”) after The Man gives her a foreboding smile, you can’t help resenting the awful justice that looks to be karmic punishment for her treachery.

Watching an actress as bubbly as Bledel wade through these nightmare scenarios is perversely entertaining, though her performance also has a point. As Becky, Bledel doesn’t act much different than she did on “Gilmore Girls” and by casting her as an antagonist, Miller and Rodriguez intimate that the moving kindness Bledel embodied on TV has no real value in their story.

In a grimly topsy-turvey way, that’s what makes “Sin City” so alluring. Yet it’s also what makes it a place where even the thickest-skinned moviegoers probably shouldn’t linger for too long. After all, as Nancy says at the end of “A Dame to Kill For,” “This rotten town…it soils everybody.”

Author bio: Bennett Campbell Ferguson is a freelance film critic and culture writer based in Portland, Oregon. In addition to reviewing films for Willamette Week, he founded the blog T.H.O. Movie Reviews, which he also edits. You can follow him on Twitter @thobennett.