There are many contenders for the best film to come out of the world’s most stylish nation. A case could be made for the slice-of-life Bicycle Thieves, the depiction of a couple on the edge of a nervous breakdown Journey To Italy, the ever-present paranoia of The Conformist, or the mystery without end L’Aventura. These are all masterpieces, conceived by filmmakers at the top of their game, and all our worthy on any greatest film of all time list.

Even among Fellini films, La Dolce Vita or Amarcord are also extremely strong bets. Nevertheless, when it comes to an Italian film that completely rewrote the rules on cinema and set the gold standard for great filmmaking ever since, no film has ever come close to 8 1/2.

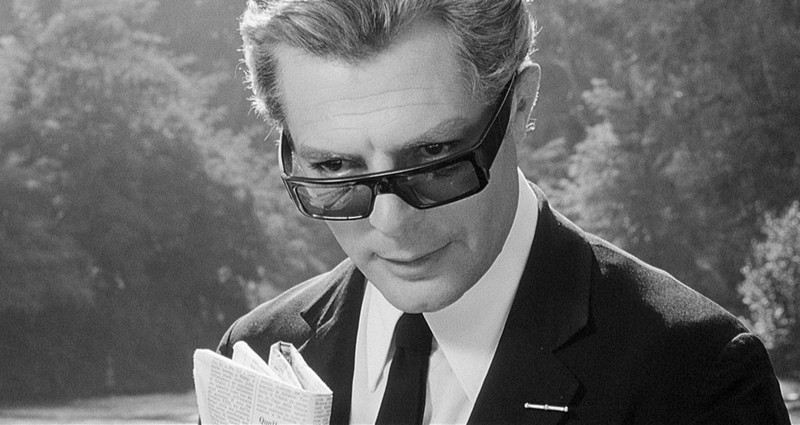

There is no one particular reason why 8 1/2 should be considered the greatest Italian film ever made. It is a sum of many shifting and at times contradictory parts, from its groundbreaking treatment of narrative, to its swooping camerawork, to the fantastic performance of Marcello Mastroianni. In the hands of many filmmakers, and of many imitators, the material would fail. There would simply be too much to juggle.

In the hands of Federico Fellini, it is alive unlike much else; a once in a lifetime phantasmagoria that would never be repeated quite the same again. Below are the eight reasons why it should be considered the greatest Italian film ever made.

1. It Treated Narrative In A Whole New Way

8 1/2 is a constant weave, oscillating between reality and fantasy, dreams and memories, easily following Guido’s life without any difficulty. In a way it follows Barthes concept of narrative as desire to a T, the ambition on behalf of the hero to make sense of his life and give it a teleological meaning reflected in the journey that the story takes.

It became so influential because it showed prospective filmmakers that a story didn’t need to be tethered to any particular time or place; rather it could float and be free, like Guido flying up in the sky in the film’s second scene.

What is so satisfying about its use of narrative is the way it opens itself up to so many different interpretations. Marxists, Freudians and Religious thinkers have all thought about the film through their own worldview. Nevertheless, the ultimate joy comes with enjoying the narrative headiness in and of itself; bringing to mind endless associations as it moves reverie-like between scenes with consummate ease.

2. Its Excellent Depiction Of Being A Catholic In The Modern World

If anyone ever wants to understand Italy through studying its art, knowledge of Catholicism is a must. A religion that looms large over the country, it loomed large over Fellini too. Raised as a Catholic, there is a nagging sense in his films that the guilt never goes away. 8 1/2 is set just near Rome for a reason. The seat of the Vatican, and thus the centre of the Catholic world, Guido is estranged from the church, yet close enough to seek salvation if only he wishes.

With his numerous sexual fantasies and constant self-abasement, he can be viewed as the ultimate lapsed Catholic; always capable of redemption but never confident enough to give it to himself, or to even take it seriously. This can be seen when, as a boy, he runs away from Catholic school to satiate over Saraghina the prostitute. He is shamed for his love of women, unable to understand that whores live in sin when they are so beautiful.

This guilt and mixed emotions manifest themselves later in Guido’s life, giving rise to a complex artist who, try as he might, cannot understand what it means to authentically depict somebody who has been raised a Catholic. What Fellini did so well was draw a sneaky parallel between Catholicism and Freudianism, arguing that they sometimes can feel like two sides of the same coin.

3. It Pioneered the Concept of Autobiography In Film Like No Other

It is famously called 8 1/2 because it is Fellini’s 8 and a half movie (he made two shorts and a collaboration, hence the half). The film is about a director struggling to make a film, an obvious reflection of Fellini’s own writing block that existed after the success of La Dolce Vita. One gets the sense that Fellini had so many memories and ideas that he wanted to dramatise into one movie that the only way to depict it all was through the unique form of 8 1/2.

There were autobiographical movies before, but no one had hitherto taken the internalisation of oneself to such a narcissistic and infinitely probing degree. Yet, the reason it doesn’t descend into complete solipsism is due to the brilliant performance at its centre. Marcello Mastroianni, with whom Fellini would collaborate several times, giving a career-best performance here, is always slyly self-aware of being on show. He is so enjoyable to watch he stops the film from being too self-centred or neurotic.

With his childlike but conflicted mind, he is the perfect conduit for the film’s many contradicting themes. Many filmmakers would, in later films, use the template of 8 1/2 to write and direct their own highly individualistic stories, but few have ever walked the line between self-representation and egocentrism as delicately as Fellini does here.

4. The Camerawork Is Indelible

If any definitive statement can be made about 8 1/2, here’s one that is irrefutable: the camerawork is simply indelible. Fellini, building upon his excellent work in La Dolce Vita, moves his camera with a wild sense of abandon that perfectly complements its unconstrained artistry.

Floating through hotels, beaches, fields and courtyards, it works as both Guido’s constant canvas and paintbrush, depicting both the world he sees and how he sees that world, and how we see him act within that world. It is a showcase in constantly shifting perspectives that only the cinema could make so enjoyable ambiguous.

Yet it isn’t all tracking shots and wide pans. Fellini is a master of depth and close-ups too, knowing exactly where to place the camera in order to stress each and every emotion. Given that the structure is basically episodic — in reality one of the hardest forms to master — the camerawork is what keeps one’s attention held rapt throughout.

Credit must be given to cinematographer Gianni Di Venanzo, whom also worked with masters Michelangelo Antonioni and Joseph L. Mankiewicz throughout his distinguished yet tragically short career. Without his incredible contribution, 8 1/2 may have been a very different (and probably lesser) film indeed.