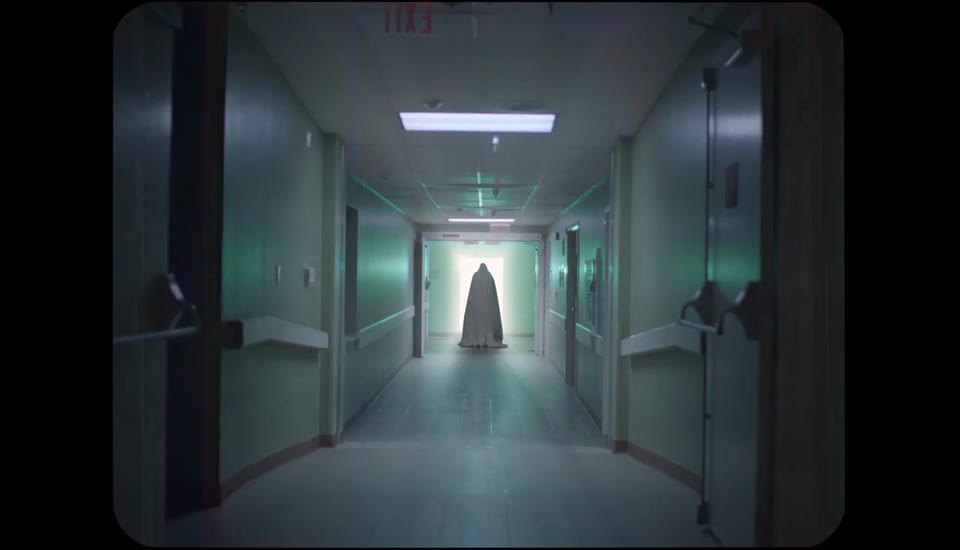

4. The striking cinematography

With the ache of nostalgia permeating the picture, the square frames of A Ghost Story instinctively feels right. So, it’s now wonder that Lowery chose to shoot the film in a 1.33:1 aspect ratio, which also gives the impression that the story is told to us in fleeting, mournful snapshots stashed in a place where it now seems half forgotten.

In Lowery’s own words he says that “[A Ghost Story] is about someone basically trapped in a box for eternity, and I felt the claustrophobia of that situation could be amplified by the boxiness of the aspect ratio.”

Working for the first time with Hannah Fidell’s regular cinematographer, Andrew Droz Palermo (A Teacher [2013], 6 Years [2015]), Lowery has a gifted camera man who can lens with restraint and panache, when called for. Inspired by the photographs of Gregory Crewdson, there is a wonderful fusion of the surreal and suburbia that adds to the half-lit cool.

While the film has a languid, at times quick-as-molasses pacing, and an affection for close-ups, it also shows deepness and dynamism as the story progresses (scenes in a crowded house party, a gleaming, futuristic city, and a bucolic pioneer campsite are photographed with wonderful depth of field and color saturation, for instance). It’s not flashy, but it’s frequently dreamy (a shot of cobwebs reflecting light in the vacant home is particularly memorable).

3. That scene with the pie

The film’s most buzzed-about, discussed, dissed, misunderstood, and now rather notorious scene is the one with Rooney Mara and a pie. Here’s the set-up: shortly after her husband dies, the widow makes arrangements to sell their home. As arrangements are made, the real-estate agent drops in with some paperwork as well as a pie, as is custom to bring comfort to those in mourning. Mara’s character returns to her home, finds the pie and proceeds to eat said pie. So what’s the big whoop?

Sniffling, her eyes deep set, she sits on the floor of her kitchen and proceeds to stab at the pie, her fork like a weapon, devouring the entire thing in one shot, in real time, with a static camera. The scene runs for just over five minutes, and it communicates for the first time since her husband’s death, her palpable, pained, and super-colossal sorrow. The ghost is there watching her, but he is powerless to act, and can only react to his lover’s lonely anguish. In watching this scene stretch out as a long take, we too are complicit in her lament.

The lighting is diffused, there’s a blue hue to it all, the faint sounds of traffic and distant voices trailing by outside help to remind us of the passage of time as she viciously stuffs more pie into her mouth. There’s no delight at all in her act of eating, just a sickening determination. Finally, after an agonizing eternity, Mara ups and runs to the bathroom, though the camera frame remains the same, she’s now in the background periphery and we can hear her retching in the restroom.

This painful sequence, exposed, raw, and voyeuristic, comes at us as a deliberate and designed statement of ideals and tenets. Once we suffer through this excruciating experience, we can look back on it with erudition, maybe even survivor’s guilt.

2. The film plays with the concept of time in startling ways

As the ghost haunts his former home he becomes bound to it. Eventually his wife moves on, leaving behind her old life with him for some kind of happiness that she deserves, having spent an unspecified but obviously very lengthy time wracked in depression, grief and worry. She departs and then a procession of other tenants live in the house.

From scene to scene we see the abode move from empty, to full, glimpsing along the way; a Spanish-speaking single mother and her two children (whom the ghost sees fit to eventually terrorize); a house party which includes a philosophizing motormouth played by Will Oldham (perhaps better known for his musical career under his stage name Bonnie ‘Prince’ Billy); eventually the home falls to ruin and is demolished and razed; next it becomes a construction site; then a glazy skyscraper amidst what seems like a Blade Runner-like future of swelling population and pollution.

After wandering the fallow halls of tomorrow the ghost manipulates time, moving backwards yet bound to the same geography. He visits where his home would one day stand when it was the new frontier and pioneers camp there (as well as their massacre at the arrows of Indians). A jolting jump cut shows us the skeletal remains of a pioneer child sprouting springtide flowers.

As the ghost moves around through time a twist reveals itself as the film revisits a sequence from the prologue. At the onset of the film our married couple, settling into their new digs, were awakened by a conventional bump-in-the-night. Seeing this scene again from the ghost’s perspective we realize that he was haunting himself this whole time.

From the ghost’s standpoint, time is a wheel. The circular aspects underscored by artful ellipses and the notion that we may all be haunted by ghosts of our future selves.

1. A Ghost Story details a gifted director doing exactly what he wants to do

Ambitious and idiosyncratic, perhaps even to a fault, this is a film that top to bottom presents the vision of its creator. It’s fair to say, in my estimation at any rate, that David Lowery ascribes to the auteur theory inasmuch that this film is his own very personal conception.

Having made his first Hollywood production, Pete’s Dragon (2016), who’s budget dwarfed all of his previous efforts, Lowery sought out his next project as something of a palette cleanser as well as an artistic tonic. It’s not that his experience with Pete’s Dragon wasn’t a rewarding one, or one that allowed him to express his innovation and style, but it was, as studio pictures so often are, a by committee, and often too-many-cooks scenario.

And so, seeking to do something experimental, fast, and dirty, and working from a long gestating idea Lowery had that spawned from an argument his wife and he had (about moving from the sticks of rural Texas to the bright lights of Los Angeles), the seeds for A Ghost Story were sown.

Lining up a low-rent team of past collaborators (including, as previously mentioned, his cast, who both wanted to work with him again), Lowery self-financed film and shot it in secret. When details of the film were detailed in its first press release the project was already in the can.

“[A Ghost Story] was such a high-wire concept,” Lowery told The Guardian during the press junket for the film. “I went into it thinking it would be fun, a liberating bout of creative experimentation. But it was terrifying.”

With something very close to carte blanche, Lowery explores a solitary man’s desire to understand the woman he loved (and perhaps never really knew), his own stubborn inability to let go, and also his dogged, I’ll-spend-eternity-if-I-have-to attempts to recover and read a squirreled away scrap of paper.

Lowery’s sad speculations and possessed presentation is a slow burn that disquiets the viewer and follows them home. Hidden in plain sight, among the Hopper-esque vistas, vacant lots, and semi-dark skies, A Ghost Story is an artful examination of love, life, and death as espied through crudely snipped eyes in ethereal linen.

Author Bio: Shane Scott-Travis is a film critic, screenwriter, comic book author/illustrator and cineaste. Currently residing in Vancouver, Canada, Shane can often be found at the cinema, the dog park, or off in a corner someplace, paraphrasing Groucho Marx. Follow Shane on Twitter @ShaneScottravis.