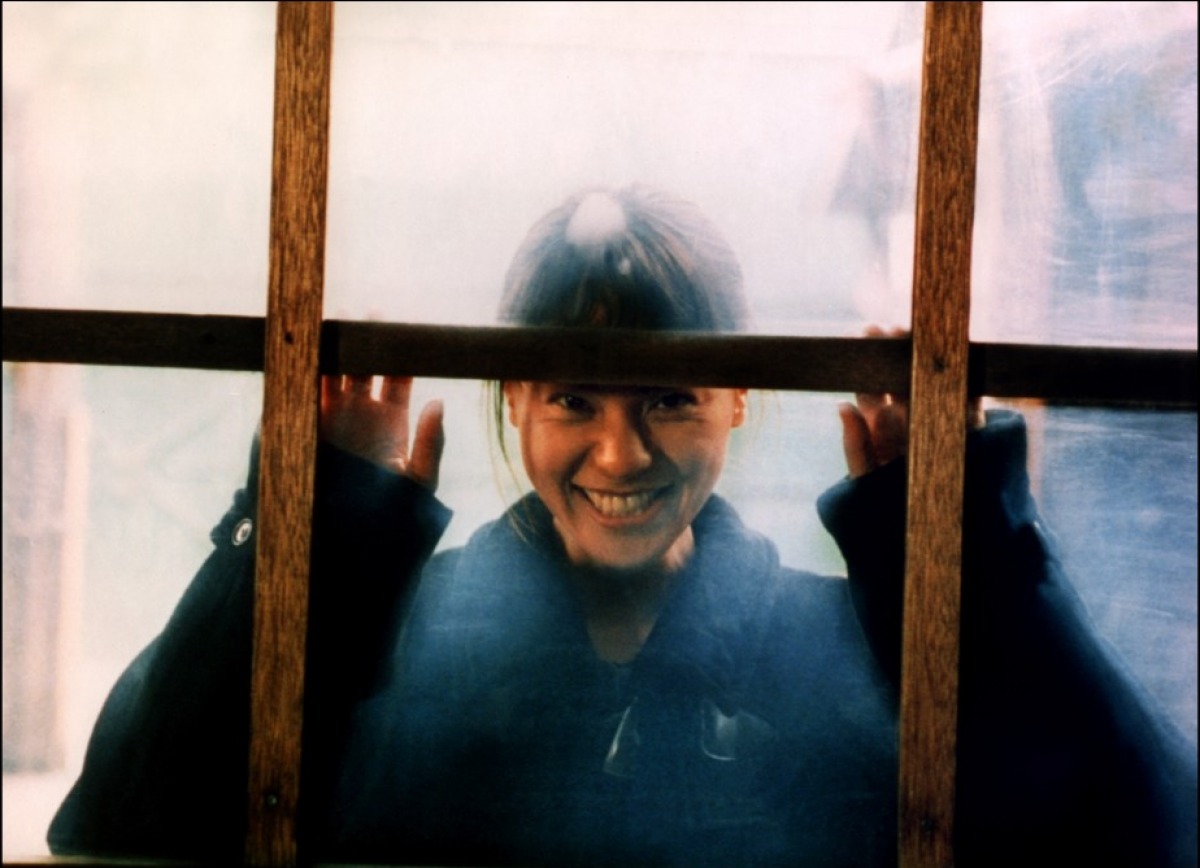

6. Maborosi

Koreeda’s debut exemplified the influence Yasujiro Ozu had on him, as it established him as the master’s contemporary successor.

The film revolves around Yumiko, a happily married woman with a 3-month-old baby. Her life changes radically when her husband dies in an apparent suicide. A few years later, Yumiko agrees to an arranged marriage with a widower, Tamio, and the three of them move to his birthplace, a fishing village.

Koreeda directs a film where grief is the main subject, as Yumiko demonstrates it in subtlety. Every aspect of the film works to express this feeling, including the long shots, the use of natural light, the slow pace, and the melancholic soundtrack. Makiko Esumi gives a great performance in the protagonist role.

5. Our Little Sister

Three sisters, Sachi, Yoshino and Chika, live in a large house in Kamakura. When their estranged father dies, they travel to the country to attend his funeral, where they meet their adolescent half-sister, Suzu. A deep bond is quickly formed between them and results in them inviting her, who is currently orphaned, to live with them. She accepts gladly and a new life begins for the four sisters.

Koreeda proves once more that he is the contemporary master of the family drama, directing a film that is genuinely Japanese in its themes, pace, and characters. He focuses on the human interaction between the sisters, portraying their everyday lives, feelings, and thoughts, and all the little moments that define us as humans.

One of the film’s biggest assets is the strong performance from its cast. All of the actors in the movie seem to have adapted perfectly to the restrained style of acting Koreeda always demands from his actors. Haruka Ayase (Real, Dearest) as Sachi and Masami Nagasawa (Wood Job!) as Yoshino have the most demanding parts, since they also have to present a number of tensions, which stray a bit from the permeating calmness and subtlety of the film. However, they both deliver in wonderful fashion.

Of equal excellence is the cinematography that focuses, apart from the protagonists, on the city of Kamakura, presenting it in a rather picturesque fashion. Although the film lacks any kind of action and the pace is quite slow, Koreeda’s evident lyricism and attention to detail compensate fully.

4. Like Father, Like Son

“Like Father, Like Son” was a great success at the Japanese box office, netting the 10th spot in 2013, and it won the Jury Prize from the 2013 Cannes Film Festival, along with a number of awards from festivals all over the world.

Two families, the Nonomiyas of the big bourgeoisie and the Saikis of the petit one are informed that, during their infants’ stay at the hospital’s maternity ward six years ago, a nurse mixed up the two boys, thus resulting in them in the care of the family of the other. Both of the families are now standing against having to switch their children, after investing so much in them.

The film then progresses on pinpointing the differences between the two families, presenting them in kind of ironic way. The Nonomiyas live in luxury in a prestige flat, and they raise their child with the sole purpose of becoming a successful businessperson, according to the will of the father, Ryota. On the other hand, the Saikis live with their two other children in an old and small house, where Yudai’s shop is also situated, and they retain a generally loose life theory, without many rules.

The parents, having to confront the inevitable, decide that each child has to spend some weekend time with his actual family, in order for the transition to be as smooth as possible for everybody. As time passes some difficulties surface, since the Saikis, although poor, seem to be better at parenting, particularly from Ryota, who is absent due to his work.

Yudai, on the other hand, spends plenty of time with his kids, thus making them very happy. However, he is somewhat irresponsible, mostly concerning his professional and financial situation.

Koreeda, who also wrote the script, brings two subjects into focus. First, the class difference that still exists at large in the urban environment of the Japanese metropolis and the effect it has in the upbringing of children; and second, he presents a question about the component that makes a man feel like a father. In order to demonstrate these two topics, he uses the two male leads almost exclusively, while the women and the kids have distinct secondary roles.

3. I Wish

“I Wish” highlighted, once more, Koreeda’s ability to draw impressive performances from children, this time from real-life brothers Koki and Oshiro Maeda.

The script revolves around two brothers, Koichi and Ryu, who were separated after their parents’ divorce. Nozomi, the mother, has returned to Kagoshima, where she lives with her parents, working at a supermarket. The father, Kenji, stays in Osaka, where he fails to keep any job he gets, instead focusing on his band, in a tendency that led Nozomi to abandon him.

However, the two brothers start to miss each other and Koichi eventually comes up with a plan for them to rejoin, when he learns that that the two newly built bullet train lines create a supernatural energy at the point where the trains meet each other, and can grant any wish one utters at that moment.

The film eventually becomes a coming-of-age journey for the two kids, to a resolution of their issues that is less than one would expect, but fits perfectly the permeating realism of the film. In that fashion, “I Wish” deals with everyday life in Japan, particularly regarding children’s lives, while Koreeda also adds some other episodes to the story to make it more entertaining.

Koreeda refrains from taking a clear view on the subject, but makes a clear comment regarding life through Kenji, who at one point states, “There’s room in this world for wasteful things. Imagine if everything had meaning. You’d choke.”

2. Nobody Knows

Inspired by a true 1988 incident known as the “affair of the four abandoned children of Sugamo,” “Nobody Knows” established Koreeda as a skilled filmmaker in directing child actors.

Four siblings from different fathers reside with their mother in a small apartment in Tokyo. According to her building proprietor, she appears to have only one son, Akira, the oldest of the four, while hiding the others in order to keep the rent at a minimum. At some point, she abandons them, leaving them only some money. Akira now has to take care of everyone, since the rest of the kids have to stay inside the house in fear of being noticed by the proprietor.

Koreeda directs a very carefully edited movie, whose initial point of excellence is the avoidance of becoming a bromide melodrama. His perspective is completely realistic and the script flows at a slow, minimalistic pace.

The allegory is obvious: The alienation of children in the cruel, lonely, and irresponsible environment of the metropolis, and the social neglect of their constant needs of protection, love, ethical and emotional support.

Excellent performances by the 14-year-old Yuya Yagira, who won a number of awards including the one for Best Actor at the Cannes Film Festival and You, who plays the mother.

1. Still Walking

“Still Walking” is a distinct example of Japanese cinema, in both themes and technique, and is the one that established its director as the definite successor of Yasuhiro Ozu.

The son and daughter of the Yokoyama family return to their parents’ house in the country to commemorate the death of their brother, who accidentally drowned 15 years ago. The son, Ryota, has recently married a widow with a young son and has brought them along; the daughter, Chinami, has come along with her husband and their children. However, tensions that preexisted now move to the foreground.

Koreeda directs an ode to realism, a fact stressed by the tensions and the general feelings occurring between the members of the family, which are similar to the ones of every household. The camera use, which is situated extremely close to the set, makes the spectator feel as though he is present in the house where the movie occurs, participating in the discussions at the table and walking around with the protagonists.

Apart from the above, the pace is slow, the dialogues meaningful, the exaltation non-existent, the focus on detail great, and the acting sublime, in a true Ozu fashion, however in contemporary terms.

Author Bio: Panos Kotzathanasis is a film critic who focuses on the cinema of East Asia. He enjoys films from all genres, although he is a big fan of exploitation. You can follow him on Facebook or Twitter.