Australian director Peter Weir has had a fairly long and distinguished career as a true master of his craft, earning him a wealth of award nominations and wins across the thirty odd years he has spent creating some of the most wonderful, life-affirming cinematic yarns of the period. Of course, there’s actually a fair amount of variety to Weir’s output as a director, taking in horror, documentaries and television work as well, and whilst he may perhaps be best known for his work inside Hollywood, his early films remain as engaging and as challenging as ever.

He has ultimately proven himself to be a challenging and consistently brilliant film maker throughout his distinguished career, and might even be considered the greatest of his ilk to come out of his native Australia. Taking in only his films of feature length, here we rate his output from worst to best.

14. The Cars That Ate Paris

Weir’s feature-length debut effort is something of an oddity among his oeuvre, a vaguely socially conscious horror number based around a small town in the Australian outback. In this rather queer little municipality, the chief source of financial income is derived from luring tourists to a grisly end in automobile “accidents” with the remains of both driver and vehicle being stripped for anything remotely valuable. Those who survive the crash on the other hand find themselves with a worse fate in store, which is perhaps best left unsaid so as not to ruin the surprise for first time viewers.

The stature of the film has grown somewhat since its mid-seventies release, but there is simply no escaping the fact that for a “horror” film, there is perhaps too much emphasis on story exposition through dialogue and not very much going elsewhere, so it does demand a bit of patience from its viewers. For a deadpan piece of black-comedy, however, The Cars That Ate Paris certainly isn’t a bad film, but for most, the change in career that Peter Weir made following this was likely a more than welcome one for most fans.

13. The Plumber

A made for TV movie, but a pretty strong, somewhat absurd effort nonetheless from Weir. In The Plumber, a liberal, academic couple find themselves falling prey to the languid work rate and whims of a workman that they never even called as he invites himself into their home to set to work on their drainage system, turning what were once perfectly working pipes into a job lasting several days. As time passes, the man’s behaviour becomes progressively peculiar, leaving the couple unsure what to do about the situation and the wife, Jill (Judy Cowper) struggling to complete a thesis for her Masters in Cultural Anthropology.

Ultimately, whilst The Plumber perhaps loses its way a bit as it goes on, what we have is Weir striving to incorporate another slice of social commentary, highlighting significant differences between the haves and have nots.

The couple for instance are wealthy liberals, yet seem more concerned with how they ought to behave in the eyes of others whilst the poor, uneducated plumber – who laments at the lack of respect displayed to him – is certainly not afraid to get his hands dirty and simply do what needs to be done. For Weir, the poor remain true to themselves rather than bow to stifling social conventions, a theme that would obviously show up later in the director’s career, notably Dead Poets Society.

12. Green Card

As he moved in the nineties, Peter Weir directed this romantic-comedy that sees the brilliant Gerard Depardieu (Georges) looking to marry with the purpose of securing himself a green card and citizenship within the United States so that he might take employment there. Cue Andi McDowell (Bronte), a keen gardener who appears to have found her ideal New York apartment complete with a greenhouse on the roof, there’s just one snag; the apartment is for married couples only.

The two enter into a marriage of convenience, but as one would expect from a Hollywood film, the two eventually fall in love over the course of its 108-minute running time, despite their initial animosity for one another.

There’s certainly nothing new to be found here, it’s a fairly by the numbers affair, but the script’s pretty solid – despite some discrepancies regarding Georges’ passport – and the two leads work well together so the end result is, as the tagline claimed, “an irresistibly charming comedy”.

11. The Mosquito Coast

On paper, The Mosquito Coast sounds almost too good to be true, combining the director with the acting talents of Harrison Ford and Helen Mirren as a couple that take their family (which includes the late River Pheonix) to some fictitious Caribbean island after becoming disillusioned with America’s consumerist society.

Unfortunately, the end result is a film that falls just a tad short of the mark, losing its way somewhat as it drags on towards the end, but there are some hugely positive aspects about it, most notably the performance of its leading man. Ford is immense as the inventor turning his back on a society that has rejected both him and his latest invention, making the movie something of a character study as he tries in vain to build an idyllic environment for his family where they live off only what nature provides.

Of course, not everything goes to plan and the idyll begins to tumble down around them creating divisions within the family unit.

It’s certainly not a perfect film, but with some truly terrific performances from it’s A-list stars and an anti-consumerist philosophy backing it up, The Mosquito Coast is definitely worth a look.

10. The Year of Living Dangerously

The 1983 Oscar winning period political-drama is a film with a big reputation and an even bigger cast, including the diminutive actress Linda Hunt who earned the Best Supporting Actress award for playing male photographer Billy Kwan. The narrative follows Mel Gibson who portrays a young, idealistic photographic journalist who finds himself in Indonesia in 1965, a hotbed of a country hovering precariously upon the verge of bloody revolution.

Amid the goings on he finds that the foreign interested parties treat the situation, and its potential impact upon the locals with little more than disdain. They perpetually live the high life, sipping champagne at parties whilst the people around them live in abject poverty and misery, with only Kwan showing the slightest sense of remorse and empathy.

The Year of Living Dangerously, in terms of its narrative, seems to sorely lack focus and as a result any message that the director was trying to communicate becomes lost, yet in terms of how he captured both the look and feel of the environment, the film is astonishing; the tension is palpable throughout and it is this that manages to keep viewers interested from start to finish.

9. Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World

A big budget high seas romp that arrived some five years after The Truman Show which sees Peter Weir taking on a story concerning two ships effectively playing tag out in the middle of nowhere. The film is actually based upon two books, which perhaps makes it a tad surprising that in terms of its narrative, there’s not exactly much to write home about here and yet, Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World is a surprisingly satisfying action film.

What story there is revolves around the friendship that blossoms between the captain and doctor of a frigate, played by Russell Crowe and Paul Bettany respectively and, in typical Hollywood fashion, these are two men with greatly differing views of the world who come together out of mutual respect, much like a good old-fashioned buddy movie.

What elevates Master and Commander though, aside from some stunning effects and set-pieces is its attention to detail, the world in which it exists a living, breathing one that makes it difficult to remove oneself from, the battle sequences are elongated and thoroughly intense and this is all bolstered by some truly astonishing sound design. It’s by no means the most intelligent film that Peter Weir has ever made, but as far as sheer spectacle goes, this is the biggest and best film that he’s ever created.

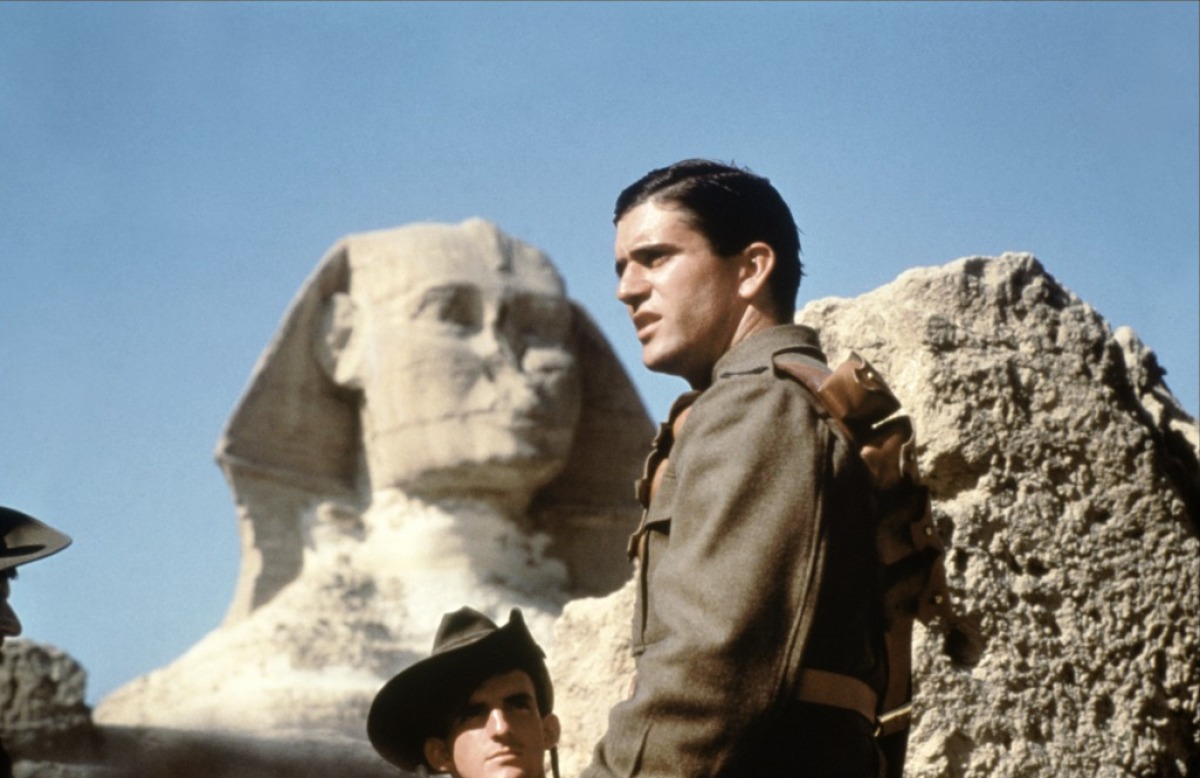

8. Gallipoli

An overtly anti-war flick that stars a young Mel Gibson (the first of his two collaborations with Weir) in what might very well be the most outstanding performance of his career as one of two friends (both athletes) who sign up to fight for their country during the First World War. Naturally, the focus of Weir’s film is on the catastrophic offensive that the allies launched in a bid to capture Constantinople, it was the very first outing for the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps who, led by inept officers, suffered tremendous losses.

Gallipoli is something of a game of two halves, opening in Australia as the two runners sign up and make a bizarre trip across the outback as they debate the pros and cons of enlistment, it’s not exactly the opening that most would expect, but the bleak, barren landscape has been so beautifully photographed that it is still sure to take one’s breath away.

The attention to detail in the costume design is sublime and the battle scenes, which feature hundreds of extras are still stunning as the film steam rollers towards an inexorable and gut-wrenching finale. There have been some complaints about historical accuracy, but quite frankly this is a fairly trivial concern as Gallipoli is an emotional rollercoaster ride and a beautiful statement on the futility of war from its director.