There are few directors in film history as polarizing as Peter Greenaway. Initially trained as a painter, Greenaway has a terrific mind for visual framing and composition. This inspired stylistic mind and passion for details make his filmography like no other, with each frame a calculated painting, and sometimes several paintings in one.

Not only does Greenaway use his mastery of the camera to create his visions, but he is one of the greatest utilizers of after effects and editing tricks in the business, leaving his films with an instantly recognizable feeling.

Just as importantly, of course, Greenaway makes very interesting films in terms of content as well, and his subject matter is similarly unique and eccentric. The plots of his films are never conventional and often told in an experimental style. Thematically, Greenaway is as adventurous as he is with his visuals, taking on controversial topics in graphic form, often featuring somewhat gratuitous nudity as well as disturbing imagery.

The quality of each of these films, and this list’s rankings, is somewhat subjective, but there are clear standouts on both the good and bad sides of the spectrum. Near the top of the list you will find carefully thought out films with gorgeous visuals, captivating plots and a good balance of form and substance. While all of the films exhibit the director’s strong vision, some of Greenaway’s films near the top of the list show less restraint and are more indulgent in style over substance.

15. 8 ½ Women (1999)

One thing that can be said about Peter Greenaway is that his films never lack vision. Even his least enjoyable films, like 8 ½ Women, are precisely, or very nearly, the films that he set out to create. Another thing that can be said about the director is that he does not seem to care if his audience enjoys watching his movies.

This curious film, about loss, grief and sexuality, certainly has a clear direction with every shot, but it is certainly not an enjoyable film to watch. It follows a father and son who, after losing their wife/mother, cope with their loss by enlisting eight and a half women (the half being an amputee) to live at their mansion and have sex with them.

Unfortunately, this is the bulk of the film’s plot and much of the time is spent discussing, but curiously, not showing the sex. Greenaway’s calculated dialogue and eccentric shots and effects maintain the audience’s attention, and even presents some interesting food for thought, but certainly to a lesser, and more uncomfortable, extent than his greater movies. The title, of course, stems from Fellini’s film 8 ½ which the father and son watch several times throughout the film.

While I could not determine exactly the reason for this reference, I am quite sure that the realization would not improve the experience much. Although 8 ½ Women is a unique film and challenges the viewer more than most mainstream fare, unless you are a completionist, I wouldn’t bother searching this one out.

14. Goltzius and the Pelican Company (2012)

The second film in Greenaway’s supposed “Dutch Masters” trilogy, the first being Nightwatching and the final being a rumored picture on Hieronymus Bosch, this movie follows Hendrik Goltzius, a master engraver. He convinces a rich Margrave, played by F. Murray Abraham, to buy him a printing press so that he can make books of his, mostly erotic, prints. An addition to the deal is that Goltzius must put on a show for the Margrave and his guests, depicting in real life each of the acts in the prints.

The plot itself is not alienating, in fact it is quite compelling in many instances, however, this film is certainly one of the director’s least accessible, and unfortunately, one of the least worthwhile. The combination of visual effects here are at an all time high, including but not limited to, extreme color-correction, overlaid text and frames in frames.

These efforts make the screen nearly always oversaturated with information and action. Not only is this exhausting on the eyes, but it also significantly clouds the mind of the viewer, making it impossible to pick up on all of the film’s messages.

13. Eisenstein in Guanajuato (2015)

Finally Greenaway makes a filmmaker the central character of his films, rather than the many artists of his past films. It has been no secret in his career that classical painting has held a large influence over the director’s work but finally we see him pay tribute to a master of a craft that he pursues professionally.

The great Russian director Eisenstein, of classics such as Battleship Potemkin and Ivan the Terrible, is shown here in the middle of his career as he attempts to make a film in Mexico. Like all of Greenaway’s biopics, the historical facts are shaky at best, but of course, this is never a concern for such a formalist director.

Heavily stylized still, but Eisenstein in Guanajuato is a welcome display of self-control from Greenaway who keeps his weird techniques simmering, partially because of the heavy utilization of footage from Eisenstein’s own films. Other than being an interesting character study, the film regrettably does not venture much further in scope.

Like too many of Greenaway’s more recent films, it too often ventures into gratuitous nudity in absence of any intrigue or plot. Similarly, the acting in this film is more similar to caricature than actually human. While not his most notable or memorable film, this portrait of a filmmaker is a welcome show of control and a welcome reminder of Greenaway’s mastery of the camera, rather than application of after effects.

12. The Baby of Macon (1993)

The Baby of Macon is a very interesting entry in Greenaway’s filmography. The film concentrates on a play of the same name, set in the 1600s, being performed in front of an audience. The central play follows a small town where all the women have become sterile through disease.

Miraculously, an old hag gives birth one day to a boy who becomes adored throughout the town. One conniving girl claims that it was herself who was the mother, through virgin birth, paralleling the birth of Jesus. She enlists a young man, played by Ralph Fiennes, to pose as her husband but soon enough her lies are exposed and she is punished, horribly.

Unlike many of Greenaway’s films, this movie does not place visual splendor over thematic content. In fact, this is quite certainly his least visually impactful film, mostly due to it being a filmed play. The themes, however, are more developed than usual, if not too much so, where the metafictional layers and boundaries between what is a play and what is real blur.

The effect can be at many times confusing, and the ideas are some of the darkest that he has ever explored, mostly in the form of commentaries on society and religion. It is by no means an easy film to get through, with a slow pace and disturbing content, but it presents some very interesting ideas and packs a powerful punch.

11. Prospero’s Books (1991)

Based on Shakespeare’s play, The Tempest, this experimental treat focuses on the legendary library of the main character Prospero, played by the iconic Shakespearean actor John Gielgud, that he famously saves from the storm and obsesses over. Lacking a central or cohesive plot, the film instead tells the story of each of Prospero’s 24 books, narrated by Gielgud. The scope and topic of these books are extremely varied, ranging from indexes, atlases to stories of the minotaur.

Despite not having a driving plotline, the films is very captivating. With each book, Greenaway paints a unique picture. He places the subjects on screen with as much intent as an artist painting a figure, and recreates Renaissance masterpieces in real life.

To further add to the visual splendor, Greenaway experiments with multiple layers overlaid and text on screen, which he now utilizes frequently in his films. The beautiful composition of the shots, in addition to the great choreography, music and voice talents, make Prospero’s Book a fascinating study, even if it is not making an important statement.

10. Nightwatching (2007)

Marking Greenaway’s first major project since the enormous “Tulse Luper” endeavor, Nightwatching is a very personal film, and it shows, forming a much more well thought out film than usual. An idea that spreads not only to Nightwatching’s sister film Rembrandt’s J’Accuse, but also starting Greenaway on a series about Dutch artists, including Goltzius, the movie stars Martin Freeman as the iconic painter Rembrandt van Rijn.

The movie depicts the artist at a high point in his career as he paints his, now most iconic, work The Night Watch. Greenaway posits, however, that behind the famous painting lies a nefarious murder, perpetrated by its subjects, that Rembrandt tried to hint to through the use of visual clues.

Perhaps it was his passion for the painter, the painting or simply the idea, but thankfully Greenaway relies on his older knowledge of framing and visual style for this gorgeously shot film. A more conventional film for sure, the movie tackles his common themes of sexuality and art, but also tries to engage the audience with a captivating plot.

It also helps that Freeman does a terrific job in the main role; a factor that so many of his movies of late have been missing. Not without his faults, but still a welcome return to an older Greenaway, this little talked about movie is a treat for both for story and visuals.

9. The Pillow Book (1996)

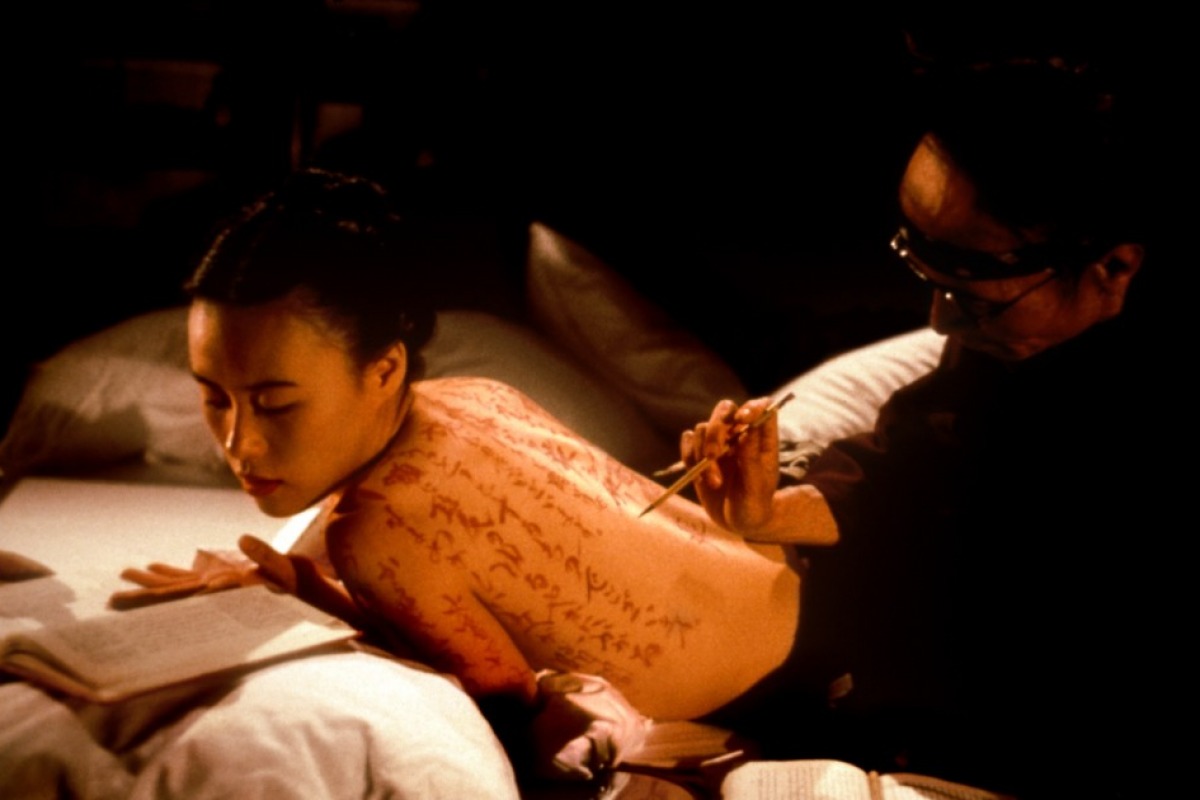

The Pillow Book takes its name from an ancient diary from Japan and follows a young model, Nagiko, who, obsessed with calligraphy, seeks to find a lover who is skilled at both handwriting, to write on her skin, and pleasuring her. After much searching and no luck, Nagiko meets Jerome, played by Ewan McGregor, a British translator who changes her obsession when he suggests instead that she write on him. She then sets on a path, writing a series of thirteen books on the skin of others.

An explanation of the film’s fractured and loose plot does not do the movie justice, as it in itself, not its true appeal. The notable aspect of the movie is instead Greenaway’s unique stylization. The Pillow Book is a change of style or the director.

Gone are the sweeping, symmetric shots of his films from the 1980s, replaced now by a wild combination of close-ups, moving text and graphic imagery all overlaid many times to create a very overwhelming, but powerful, viewing experience. I cannot say that one leaves the film feeling any more enlightened, or even with an idea of why the movie was made, but from a purely aesthetic standpoint, it is revolutionary and quite entrancing.