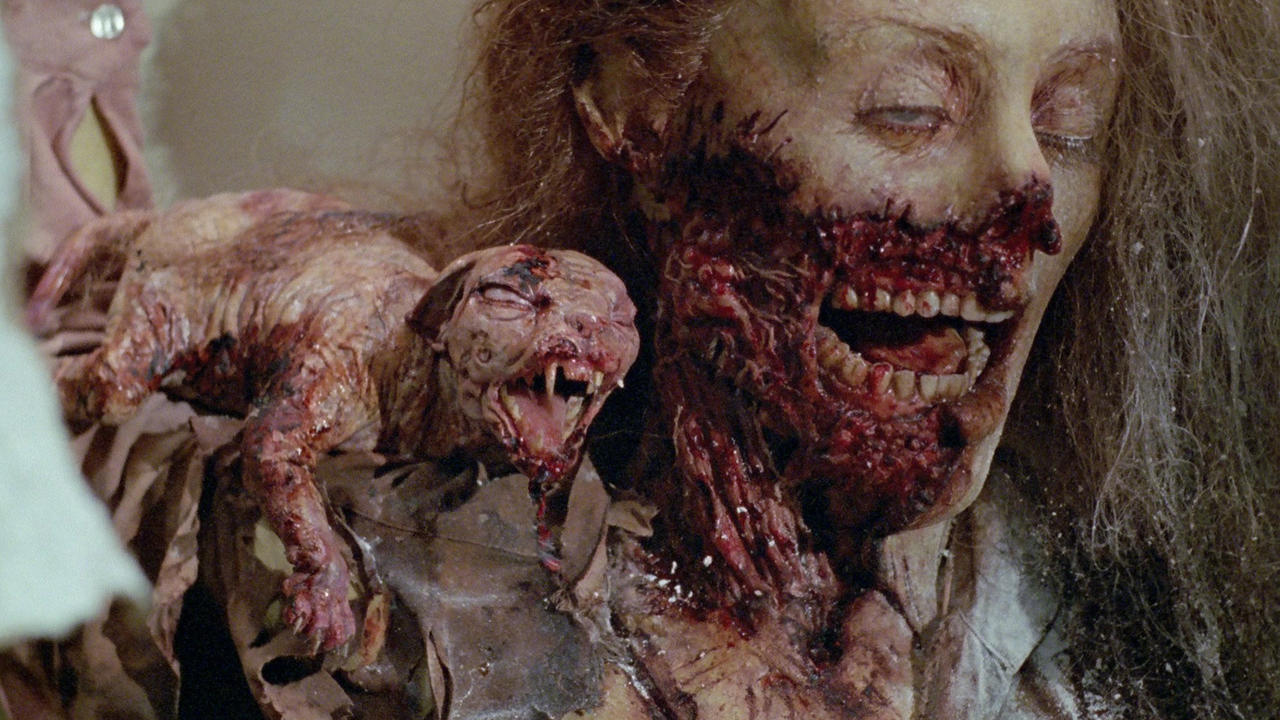

14. Mother of Tears (2007)

The third and final part of the Mothers Trilogy that began with 1977s gorgeous Suspiria is finally brought to a fairly satisfying conclusion, it’s not quite what fans were expecting after Inferno, but it probably has just enough about it for them to make do. But only just.

The plot is typically nonsensical stuff, with Later Lachrimarum revived in modern day Rome sending the entire city into a lust and blood fuelled frenzy, leaving only Asia Argento (playing a young art student) capable of standing up to the witch.

It’s all rather flimsy, but then Argento films have never really focused on story-telling, instead making up for these short comings with his baroque style and fascinating, dream-like qualities. Thankfully, whilst they may not resonate as well as they did in his heyday, there are still some traces of the old master buried in here.

The death scenes are typically exaggerated, superbly choreographed set-pieces drenched in oodles of blood, and the scene involving the baby being thrown off a bridge came right out of nowhere to both shock and surprise.

If there was a checklist for all the ingredients that an Argento movie ought to have, this would proabably manage to tick most of the boxes, but there’s just something missing, something that ties it all together. Ultimately, Mother of Tears is good, and it surely puts its contemporaries to shame, but after a thirty year wait, it’s ultimately more than a tad disappointing too.

13. Trauma (1993)

Coming across as something of a pastiche of his earlier works, Trauma lacks ambition and has one of the most convoluted plots ever witnessed in film. Argento has almost made it his mission at times to confuse viewers of his films (the opening to Tenebrae springs to mind), yet here he takes things to a whole new level.

Opening with the decapitation of a chiropractor, but cutting to a sequence involving a young boy with a love for insects as he wriggles his way inside a house, one which turns out to be the home of the killer known as “Headhunter”. The boy escapes just prior to the killer’s return home, and Argento then shows us another scene in which the character of George sees a woman watching him through a window, but this is actually the head of the woman we’ve just seen killed.

After that, the main plot gets underway, with Asia Argento’s character, Aura, escaping from a rehab clinic to meet and relate with the main male character, David, with her woes of drug dependency.

Of course, this doesn’t stop her robbing him. She gets dragged back home to her mother (Piper Laurie) and father, who conduct a séance that very night. Naturally, this gets a tad out of control resulting in the decapitations of both characters – the killer standing off in the distance holding their bonces aloft as Aura discovers the body of her mother.

The plot to Trauma almost serves as a distraction from the film, which just manages to hold together with some real stylistic touches that impinge on the realm of the phantasmagorical at times, a brilliantly over-the-top performance from Laurie and a whole raft of superb death scenes. It may not have reached its full potential, but it is undoubtedly watchable, that’s for sure.

12. Non Ho Sonno (2001)

A real throwback to the plot from Deep Red, Non Ho Sonno (or Sleepless) was something of a short-lived return to form for Argento, though as was always the case with his work after 1990, whatever strengths the film has, it was usually countered with an equally powerful negative trait to prevent him from reaching the highs he once knew so well.

The opening is entirely reminiscent of Deep Red’s – it’s both gruesome and intriguing – and from there, we are introduced to the character of Angela, a prostitute, who flees from a sadomasochistic client with a folder full of files relating to a series of murders and escapes onto a train. As it turns out, she was never safe, though who is in a Dario Argento film? The murderer has followed her onto the carriage, and thereupon stalks her through the remaining, and fortuitously empty cars.

The narrative from here-on out doesn’t quite carry the same impetus, but there are certainly some interesting facets to it, such as the Animal Farm poem (written by Asia Argento) wherein each line dictates a manner in which the film’s sadistic killer commits a slaying, it doesn’t entirely hold up to inspection, but that’s fairly superfluous. What it does do is tie in with the Freudian connection between childhood trauma and how this usually transfers across into adulthood, a theme most common in Argento films.

It’s rather unfortunate that the great Max von Sydow was never really allowed the opportunity to make the most of his role in the film, and the less said about the ending the better, but with a tremendous opening and several top-quality set-pieces, Non So Honno is undoubtedly one of the best films that Argento has made this side of the 90s. Though in all honesty, there haven’t been too many highlights since then.

11. The Stendhal Syndrome (1996)

Stendhal Syndrome is a psychosomatic disorder wherein a person experiences convulsions, dizziness, fainting and such like during a revelatory moment of clarity, this is most commonly observed when one looks at and appreciates art. It is named after the French author Marie-Henri Beyle (he used the pseudonym Stendhal) who described his own experiences in 1817 after visiting the Basilica of Santa Croce in his book Naples and Florence: A Journey from Milan to Reggio.

A similar fate befalls Asia Argento’s Anna who faints upon the sight of a stunning fresco, once on her feet again and outside, she meets a handsome stranger and here the director employs a neat trick to show how intertwined their destinies are from this fateful point onward.

There are some stunning visual hallmarks to be discovered, such as paintings that are transformed into doors into the subconscious, and what at first appears to be an uncomfortable shift in tone reveals itself to be an intelligent split that replicates Anna’s own splintered psychological state.

There’s a grittiness to The Stendhal Syndrome seldom seen in Argento’s work, and whilst it may not recoup all of its initial promise, it’s a very interesting watch nonetheless. A major detriment to the film is Anna’s voice, overdubbed against Asia Argento’s wishes, it feels strangely detached from what is transpiring around her, and one can only imagine just how good the film might have been had either Bridget Fonda or Jennifer Jason Leigh accepted the lead when it was offered to them.

10. Two Evil Eyes (1990)

A collaboration between two of the most famous and influential horror directors of all-time adapting the stories of Edgar Allan Poe for the big screen, and of the two there can be no doubt that Argento’s The Black Cat is the superior of the two. And it surely pips it for the simple fact that it’s just that bit crazier than George Romero’s effort.

In The Black Cat, Harvey Keitel takes on the role of a crime scene photographer who is compiling images together to form a sort of book of horrors whose girlfriend (Madeleine Potter) gives him a black cat. The animal takes an immediate dislike to Keitel’s character and disappears causing the girlfriend, Annabel, to blame him for it, his response to this? He murders her. Obviously.

There are literal connections between the original Poe story and the film translation whilst some aspects are omitted entirely (the gouging of the cat’s eye, thankfully), but ultimately the poor titular feline is cruelly treated and eventually hung (the form of the gallows appears upon its fur foreshadowing events yet to unfold) only to then return from the dead time and time again.

The perturbing relationship between the protagonist and the cat is not quite the terrifying ordeal as it was in the original story, but what Argento does give us is commentary on the nature of violence – like a car with no brakes, it’s all-too easy to start but near impossible to stop once in motion.

9. Cat O’ Nine Tails (1971)

Arguably the weakest of Argento’s early films, here we find him experimenting freely, attempting to push the envelope as far he can to find its limitations as well as his own creative voice. In this early film we find the director drawn towards some false scientific claims made in the 1960s that men born with an additional “Y” chromosome are inherently drawn to conduct violent acts.

The narrative follows a blind ex-newspaper reporter (Karl Malden) with an extraordinary second sight and a sharp, inquisitive mind (he always seems to ask the right questions anyway) who becomes determined to get to the bottom of a break-in at the Terzi Institute – this is shown in the opening sequence. He teams up with James Franciscus’ reporter, Carlo, and the two attempt to figure out who committed the break-in and the subsequent murder of Dr. Calabresi.

Like a good murder mystery, there are a wealth of potential perpetrators – the good doctor was also being blackmailed – and Argento throws in a wealth of red herrings into the mix to keep the viewer off the real wrongdoer’s heels, but then there’s the acting.

The performances from the two leading men greatly differ, with the Oscar winning Malden in fine form whilst Franciscus, well, flat would probably be paying him too much of a compliment.

Elsewhere the film is also a tad too inconsistent, but whilst it throws up some truly ridiculous plot points, these are typically countered all-too well with some superb scenes and spectacular fatalities, making Cat O’ Nine Tails a film that falls short of the spectacular, but for a sophomore effort, it’s certainly an interesting and thoroughly enjoyable one.

8. Four Flies on Grey Velvet (1971)

There’s simply no denying that Four Flies is pretty strange film; right from the off we are subjected to disjointed fields of view juxtaposed with images of the protagonist’s beating heart as he – Roberto (Michael Brandon) – rehearses with his band. In typical Argento fashion, he then gets himself involved in something that was seemingly none of his business to begin with, following a shadowy figure into an empty auditorium where the two struggle and, having stabbed the stranger, we watch his body tumble into the orchestra pit below.

There are less than subtle homosexual undercurrents, some focus on gender misperception and the usual Freudian commentary, with an emphasis on childhood trauma as one might expect. The latter hinted at through some superb montage segments where flashbacks are incorporated to give some indication of a fraught parent/child relationship.

There is a ridiculous piece of pseudo-science used to advance the plot and a more intriguing hint at spirituality thanks to the character known as God who manages to avoid any harm by seemingly acknowledging and embracing his place in the grand scheme of things.

Putting him aside, along with the main character who never once feels at threat despite regular nocturnal visitations from our mysterious killer, the rest of the cast are fair game, and Argento rewards viewers with his usual array of spectacular set-pieces.