4. The Consequences of Love (Le conseguenze dell’amore, 2004)

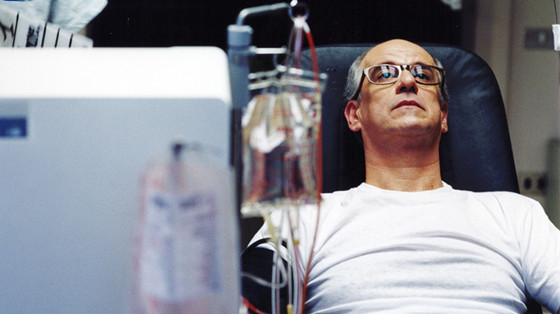

Sorrentino’s second film, The Consequences of Love, not only successfully reimagines the Italian Mafia film genre, but it is his first film that showcases the Italian director’s style and flair in all its splendor. “Consequences” follows the alienated, monotonous and joyless life of Titta Di Girolamo (Toni Servillo) as he spends his time in trivial and routine activities during his indefinite stay at an anonymous hotel in a Swiss-Italian town.

In comparison to One Man Up, Sorrentino shows unremarkable control as a director – unremarkable calibration of photography, sound, editing and acting performances – as the seemingly uneventful drama smoothly transitions into a mafia thriller.

Initially, “Consequences” conveys the emotional alienation reminiscent of Antonioni’s oeuvre – the lens’ distance from the character, the dwelling silence, and the reliance on facial expressions – coupled with Bigazzi’s attention to include physical edges and shapes from the background and décor in his compositions, allow for “Consequences” to be emotionally alienating for viewers as well as visually harmonic.

There is plenty to admire in “Consequences’” hallucinatory soundscape, oftentimes providing a sharp edge to the film’s most dramatic moments. The electric music tunes in and out with suddenness to create a sense of tension as well as contribute to “Consequences’” hyper stylistic allure. Likewise, Sorrentino successfully isolates and contrasts the silence with thunderous and razor sharp diegetic sounds in the form of gunshots and the footsteps.

Although it can be contended for “Consequences” to rate higher on the list, and if the discussion solely centered on the Italian auteur’s skill as a director, both “Consequences” and The Family Friend surely would be higher up the list. However, Sorrentino’s mafia thriller comes up short, despite being just as brilliantly crafted, in comparison to the sheer thematic magnitude Sorrentino displays in most of his later works.

Most of all, The Consequences of Love is a compelling character study that carves deep in the middle class’ routinely monotonousness, through its emotionless, disciplinarian protagonist who only reveals fears and emotional needs at the prospect of love and death. Servillo’s performance as Titta is elegant, calculative, measured like clockwork, yet overwhelmingly sympathetic.

3. Youth (2015)

In many ways, Youth unfolds as a cinematic about life’s senescence, told from various individual experiences. Although it has its fair share of flaws, Youth stands out through its showcase of a self-contained space, a bubble in the form of a luxury hotel in the Swiss Alps, in which individuals wander, fade in and out, and most importantly, express their frustrations and theories about the decadence of life, but only according to their own experiences.

Similar to The Great Beauty before it, Sorrentino merges different forms of art not only to associate, but also to expand the discourse on the connection between life’s temporariness and aesthetic repletion. Cinematographer Luca Bigazzi’s gorgeous imagery features golden lit architectural designs, exhilarating sights of the countryside, and vivid turquoise waters that coupled with David Lang’s musical compositions turn the scenery into an elegant and thought provoking landscape.

Additionally, the literature references and the choreographies such as the dancing girl and the levitating monk further contribute to the individualized soul searching overarching Youth.

In terms of cast performance, Michael Caine gives what is perhaps his most prominent performance since The Quiet American (2002). Although Rachel Weisz feels somewhat underutilized, both Harvey Keitel and Paul Dano have the prominence as well as the necessary prowess to deliver powerful lines and monologues that, alongside Caine’s, are oftentimes what hold together Youth’s segments that would be otherwise disjointed.

Additionally, the effervescent notion, episodic structure, and surrealistic visions that Sorrentino’s Felliniesque circus provides (particularly Dano dressed as Hitler and the levitating monk), allow for the story to hover over characters as they express their emotions, frustrations, solutions and theories about the machinations of life. Although Youth perhaps might not be Sorrentino’s most representative film due to a film higher up the list, it is undoubtedly his most emotional and caring.

2. Il Divo (2008)

Rather than a biographical drama based on former Italian Prime Minister Giulio Andreotti, Il Divo can be better conceived as an utterly dry black comedy and fierce political satire about Andreotti’s ties to the Mafia during his occupation.

Sorrentino’s international breakthrough, Il Divo explores with fascination Andreotti’s political machinations and motivations to maintain power. In order to highlight the edges of its satirical designs, Sorrentino shows an unwavering commitment to focus only on the web of political operations in Il Divo rather than the inner life or the emotional status of its characters as it is often the case in other of his films such as Youth.

Out of his collaborations with Sorrentino, Servillo gives what is probably his most impressive performance as the macabre and enigmatic Andreotti. Servillo’s portrayal resembles a vampirish wraith that immediately calls to mind Nosferatu (1922) and/or Dracula. Dressed in black, hunched shoulders, hands glued to his body, ears sticking out like a goblin, hovering, ever observant, through hallways and offices.

Il Divo stands among the Italian director’s films where his style – intellectual satire, absurdist fetishes, and carnivalesque and fluidly expositional camera movements – feel more integral, in tune with the premise and source material.

Bigazzi contributes greatly in using spare lighting, shadows, and dried somber colors that masquerade the buildings, offices, and hallways, which coupled with the oblique and disdainful conversations shared between Andreotti and his associates, cast the impression of a gloomy lair that oozes dark secrets, extortion, and lusts for power.

In contrast to these theatrical compositions, the montages of violence – the murders and wet jobs ordered by Andreotti – overflow with fluidity, explicit and sensationalist brutality that allow the devilish Prime Minister’s reign to feel all the more absurd and satirical.

Ultimately, Il Divo stands as one of Sorrentino’s tightest works and undoubtedly his most heavy sociopolitical statement (alongside The Young Pope miniseries) in his filmography to this date.

1. The Great Beauty (La grande belleza, 2013)

First there was Rossellini’s Rome, Open City, then Fellini’s La Dolce Vita, and then there is Sorrentino’s The Great Beauty, a tragicomedy of sheer magnitude of thematic juxtapositions – love and loss, pleasure and disenchantment, power and obscurity – while preserving uniformity in its allegorical and tonal designs. A character study that puts one man as a synecdoche for a country, its culture, and an universal preoccupation with human depravity.

The Great Beauty follows the ever-brilliant Toni Servillo as the Jonsonian Jep Gambardella, a socialite writer disillusioned with the course his life has taken as well as what the world has to offer to alleviate his existential ennui.

The middle aged aspiring journalist spends his leisure parading through the ruins and streets of Rome, hosting parties, and searching for a sense of fulfillment. Gambardella shows little concern with hiding his impotence, and instead carries himself with elegance, wry and eloquent tongue, and sentimental cynicism.

Similar to the endless groups of tourists taking photographs of the Roman ruins’ highly textured, eroded walls and the sensually grandiose statues, Gambardella embodies a notion of past glory, a bright potential wasted on the nonessential pleasures of hedonism and vanity, if not conformity.

In contrast to the visually kinesthetic and sporadic quality in Western cinema today, Bigazzi uses stylized traditional compositions, low angles, expositional and fluid movements and theatrical lighting in order to accentuate the notion of elegance and platonic beauty. Furthermore, Bigazzi employs an array of color palettes – blue and orange, red and white/black, and chiaroscuro lighting contrasts – to suit the variety of moods and themes as well as underline the passage of time.

On his first collaboration with Sorrentino, Italian composer Lele Marchitelli’s musical pieces, most of which consist of stringed instruments, and harmonic rhythm to convey a sense of amusement, cathartic tranquility and receptiveness to dramatic effect.

In consensus, the cosmopolitan refinement, the carnivalesque humor, the sociopolitical satire, and the gorgeously sensual cinematography that characterized Youth, Il Divo, The Family Friend, and The Consequences of Love operate in a higher, sharper level of sensibility concerning youth and decadence in The Great Beauty.

By the end, The Great Beauty encompasses and answers all the existential questions underlying Sorrentino’s previous films through Gambarderlla’s acceptance that all existence is but the machinations of an illusion. Il trucco.