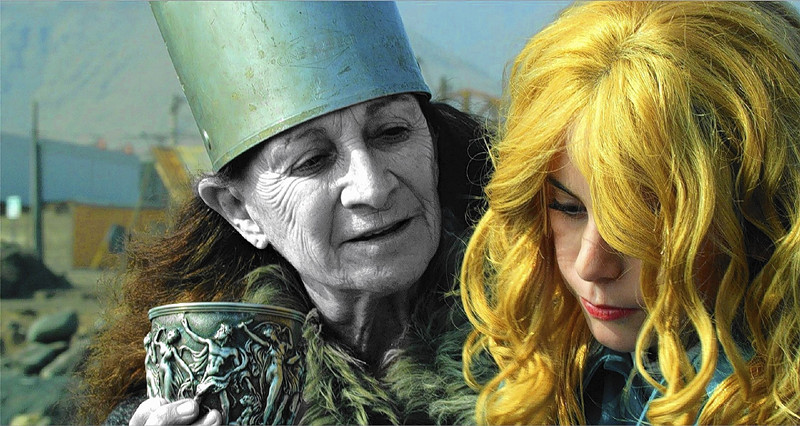

4. The Dance of Reality (2013)

Being more than 80 years old, Jodorowsky is still as vigorous and lucid as in his younger years, and the proof of that is “The Dance of Reality”, a film that marks Jodo’s return to cinema after an absence of more than 20 years. It is a cinematographic adaptation of his same-titled autobiography, and it is an exercise in self-reflection not unlike other childhood reconstructions, much like Tarkovsky’s “Mirror”, albeit less metaphysical and narratively challenging.

The story of his past is told through the filtered lens of Jodorowsky’s healing philosophy, being this and its sequel attempts to exorcise his past and to cleanse his relationship with his parents and the events of his childhood.

In this first installment of his autobiographical films, young Alejandro is wonderfully played by Jeremias Herskovits, appearing every once in awhile, silver-haired and wise, in the path of his young self with the purpose of providing guidance and encouragement, to shed a benevolent light into the dark and confusing.

While the book covers all of Jodorowsky’s life and career, this film focuses on his childhood. As expected from the prolonged hiatus in his cinematographic career, this film feels completely different from his previous works.

Age has worked in his heart, for gone is the Jodorowsky who sought to shock his audiences, who filled the screen with abundant and mesmerizing symbolism, the Alejandro who was deemed as blasphemous and dangerous. His new narrative devices are harmless poetry, compassion, and a desire to heal himself and the viewer.

3. Santa Sangre (1989)

This is the most Mexican film Jodorowsky ever made (despite being spoken in English). An aerial shot of a Mexico City barrio takes us to a colonial cathedral, in the esplanade of which an American circus has settled in.

As far as it goes in Jodorowsky’s cinema, this is the most straightforward in its critique of American cultural colonialism, making its impact in Mexican culture one of its main concerns. This anti-colonialist sentiment is paired with slight feminist undertones, making this a film ahead of its time.

The titular Santa Sangre of the film is a Catholic cult that adores a child whose extremities were cut by a couple of rapists when she tried to flee them. Fenix, the protagonist of the film, is the son of circus performers.

Orgo, his father, is the owner of the circus we saw at the beginning, and Concha, his mother, is a trapeze artist and also a very fervent member and defendant of the Santa Sangre cult. Fenix is traumatized after watching Orgo cut Concha’s arms off and then commit suicide, and thus is interned in a mental institution where he spends all of his childhood.

While originally meant to be a gore film by petition of producer Claudio Argento (brother and collaborator of famed director Dario Argento), “Santa Sangre” is much more than that. This is the work of an experienced director who has mastered his art.

The strenuous and raw spiritual energy that inhabits his first three films is still here in every event and image, but it isn’t as ravenous and demanding from the viewer; it doesn’t attack us whenever the opportunity arises. Here, Jodorowsky has managed to tame the magnificent wild beast that is his imagination, and has taught himself the self-control to employ all his knowledge and visual intuition with a purpose.

The heavy use of symbolism in his prior cinematographic efforts has been replaced with more subtle forms of communication, while also retaining the challenging nature that characterizes his films; the metaphysical revelations have turned into lucid social commentary and individual truths.

The result is a very clever film, engaging and profound, conscious of the world around it, where its setting is a key element of its narrative instead of a mere background. Easily, Jodorowsky’s magnum opus.

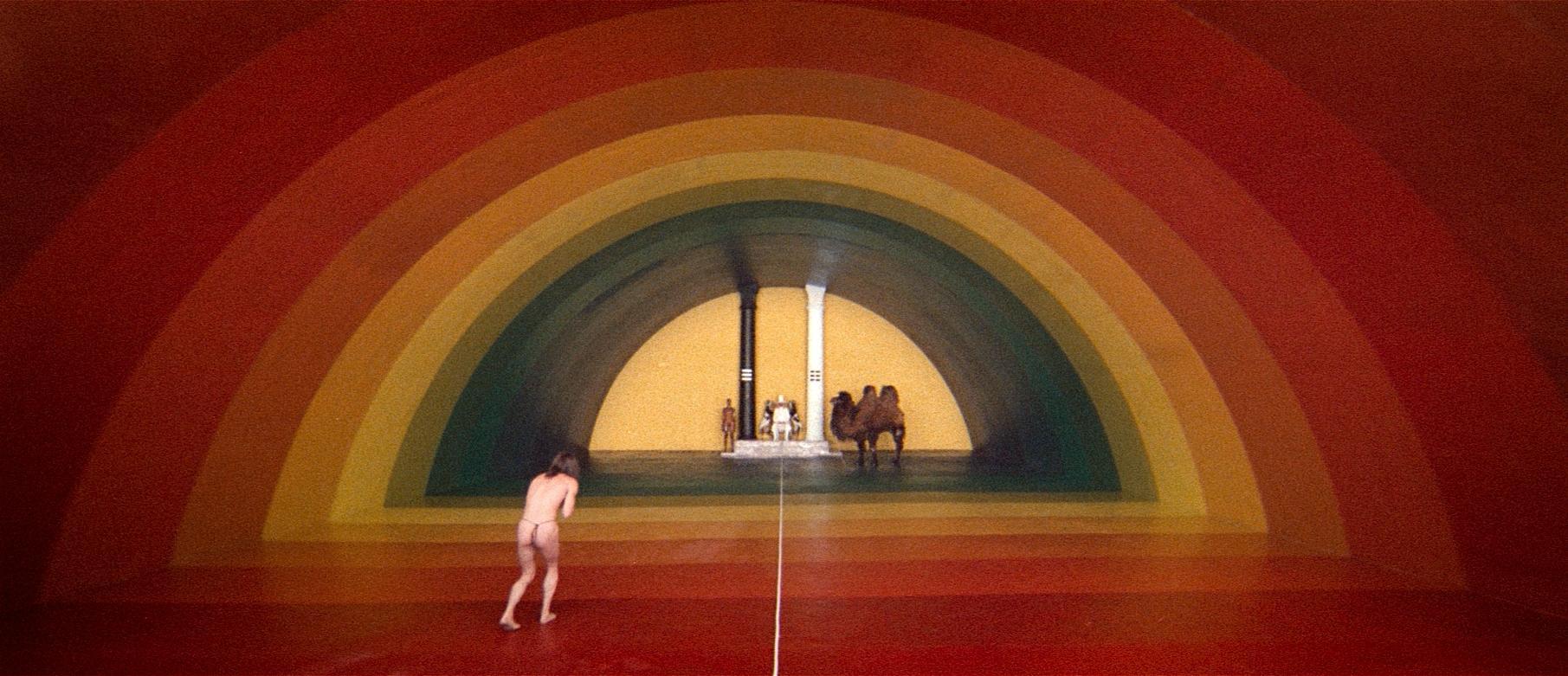

2. The Holy Mountain (1973)

In the middle of a temple, an alchemist is performing a ritual. All dressed in black, his face hidden to us, he readies his tools. Two pretty similar women sit in front of him, facing us. The alchemist strips them from their makeup, their jewelry, their clothes, and their hair. They become a pair of twins, bare and exposed, ready to assume any form that they or the alchemist desire. Such is the introduction to this film about transformation, inner searching, discovery, and spiritual awakening.

The film follows a thief – originally meant to be played by former Beatle George Harrison – who is a witness of all sorts of derangement and decay while roaming around Mexico City. After awhile he stumbles upon the alchemist of the introduction, played by Jodorowsky, who in midst of abundant religious and esoteric symbolism is subject to a spiritual training with the purpose of acquiring the ability to turn his feces into gold.

After this initial miracle, the alchemist sets out with the thief and seven other characters who personify the lowest human instincts and desires to the Holy Mountain, with the purpose of replacing the magicians who live on top and who have the power to decide the fate of the universe.

This is also one of the most politically charged works in Jodorowsky’s catalogue. In the first minutes of the film we witness the killing of civilians by the hands of the Mexican military, while the upper-class men and women lay on their knees as a form of stale religious devotion. All of this happens while American tourists, cameras in hand, consume the killing and cruelty as a form of local color staged for their entertainment.

1. El Topo (1970)

It is difficult to speak about “El Topo”, for it is a film populated by events and images whose meaning defy the knowledge of words. This is the film that enamored John Lennon so much that he decided to buy the rights to distribute it all over the US and to give Jodorowsky $1 million so he could make “The Holy Mountain”, the film that has inspired artists like Marilyn Manson, Peter Gabriel, and Kanye West. The scatological and the divine are intertwined in this film and its shocking, bizarre, nauseating, deep, colorful, blasphemous, fun, and deeply engaging imagery.

The film is divided in two parts (which have often been interpreted as an analogy with the Bible’s Old and New Testament). In the first part, El Topo (‘The Mole’ in Spanish), played by Jodo himself, is a gunslinger who roams the desert with his 7-year-old son. After finding an entire village massacred in a very cruel fashion by a group of outlaws, he sets out to exert divine justice and to bring reckoning to the perpetrators of the crimes.

Said outlaws are hidden in a Franciscan convent, where they hold the monks as hostages and subject them to all sorts of abuses. After he rescues the monks and is asked by the leader of the bandits who he is, he answers in a thunder-like manner: “I am God.” A woman who was also held in the convent is impressed by El Topo’s feat, and convinces him to go on a quest to kill the four masters of the revolver who live in the desert, thus starting the metaphysical journey of the film.

In the second part, El Topo wakes up years after the events of the first part, and finds himself in the bottom of a cave where he is adored by a population of physically anomalous people, outcasts of a nearby town despised by their deformity.

The depiction of society in this film is no different from what is seen in the rest of Jodo’s films: deranged people, religious fanatics, and hypocrites. Self-absorbed, ghost-like figures people in the town, with cruelty and hatred. After witnessing their pain and suffering, El Topo assumes the messianic task of helping the disenfranchised inhabitants of the cave reach the surface.

In the beginning of the film, a voice tells us about the moles, animals that spend their lives underground, digging, looking for ways to reach the surface only to by blinded by the sun when they finally manage to do it. A man who strives for perfection and divinity, whose efforts are hindered by his growing ego, serves as a device to tell a pretty ancient story, common to all mankind, nested very deeply in our subconscious minds.

It is the story of a pattern inherent to our existence; the transit between the sacred and the unholy, the ridiculous and the sublime, the joyful and the depressing, between life and death.

Author Bio: Gustavo Toledo was born in Mexico City and he lives there. He is a graphic design student and a freelance writer. After a tragic accident in his childhood that left him homebound for several months he discovered the magic of cinema and now he is passionate about it. Since then all he ever dreams about is making movies.