8. Mutiny on the Bounty (1935)

Frank Lloyd cleverly made two films out of this adaptation on the novel of the same name. You are first experiencing the slow degradation of order on board the HMS Bounty.

William Bligh’s vicious ways cause a ruckus amongst the crew that slowly develops into a brooding anger as the first half of the film proceeds. Fletcher Christian (Clark Gable) combats Bligh’s tyrannical ways, and then mutiny is declared. Gable and Charles Laughton’s Bligh believably create a rift that nearly tears the film strip in half.

So begins the second film, where a life is made by a portion of the crew members in Tahiti. Bligh does everything in his will to get his justice, while the defiant crew members create their own world away from what they once knew as home. Mutiny on the Bounty is a classic for a reason, as it knew how to create tension throughout the picture.

There isn’t a blatant hero or villain here, despite the different approaches to leadership. You can spot the intentions of both men, and the ability to discern your own opinion on the situation makes Mutiny all the better.

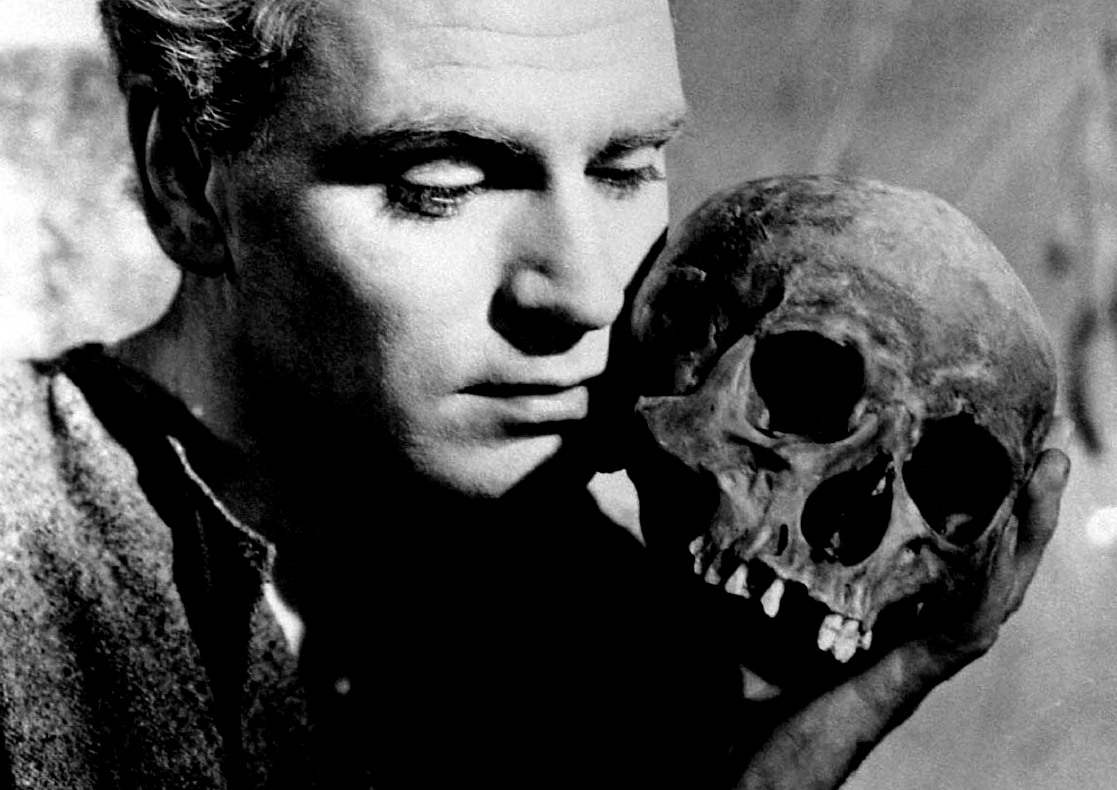

7. Hamlet (1948)

Laurence Olivier was a master of both the stage and the screen during his heyday. One of his strongest decisions was to combine the two passions that meant the world to him, and his universe brought us a modern rendition of Hamlet.

This is the only Shakespeare film to win Best Picture (Shakespeare in Love and West Side Story do not count), and, while other Shakespearean films have been terrific in the past (Kenneth Branagh is a fine and popular example), this Hamlet sticks out for its own reasons. Some of the daring moves Olivier pulled have remained controversial, including the deletion of large sections of the original play and the modernization of specific terms to make sense to unfamiliar audiences.

Hamlet’s strengths include its ability to separate itself from the original text enough to feel like a stand alone film and not yet another homage to the most fawned-over man in literature. The father’s ghost is so spooky for its time that it thus becomes a film of its era.

The sets and costumes, while expertly done and reliant on its source, also feel like the work of a ‘40s film. It may feel petty to say, but a look at other Shakespeare works will often have them feeling misplaced from their time of creation. Olivier was not afraid to timestamp his work, and his boldness has rendered Hamlet one of the strongest films of its kind because of its stern identity.

6. All the King’s Men (1949)

No, not that awful 2006 version that sullied the name of the Pulitzer-winning book it was based off of. This is the ’49 version that lived up to its iconic source material and then some. All the King’s Men is somewhat of a forgotten gem that is not just a great product of its time but one of the strongest political noirs you will ever come across.

Robert Rossen’s take on the Robert Penn Warren novel is carefully structured in a way that utilizes the change of heart of its main character (Willie Stark) as naturalistically as possible. That role is played by Broderick Crawford, and his ability to play both a man wanting change and a fearless ruler is unparalleled.

We have all witnessed the creation of an evil character out of the basis of a decent hearted goodie (this is famously covered in the Godfather films), but All the King’s Men does a solid job at this common trope. You will root for Stark until the moment it is far too late.

Regardless of how you will feel about his transition into darkness, the highly unforeseeable ending will still pull you out of your seat. All the King’s Men was not a Hollywood picture, and for a ’49 win, that says a lot. Like its main politician, the film did not take the safe route for most of its decisions, and it is a thriller that begs to be witnessed.

5. The Lost Weekend (1945)

Any cinephile will know the name Billy Wilder. He is one of the greatest director/screenwriters of any era in movie history. If you were to list off your favourite films of his, some that may come to mind include Sunset Boulevard, Some Like it Hot, Double Indemnity, The Apartment (which will be covered later in the ‘60s list), Ninotchka and more.

One of his overlooked achievements is The Lost Weekend, which is strange because the film was his first to win Best Picture. You can either expect a comedy with severity or an unnerving noir whirlwind, and is The Lost Weekend easily one of Wilder’s darkest films.

Ray Milland’s alcoholic character is a writer who creates their own ending by succumbing to their inner demons. The Lost Weekend is just that: a few days of pain and depression.

The film is complete with haunting music, engulfing shadows and even hallucinations caused by withdrawal. Sure, the film may not have been able to go as far as it wanted in the ‘40s, but it comes pretty close with this dismal collapse. If you are a Wilder fan of old or new and you have not seen The Lost Weekend yet, it is an entry you are sorely missing out on.

4. All Quiet on the Western Front (1930)

How did this film even get made? For a movie that was made on the cusp of the ‘30s and the tail end of the silent era, All Quiet on the Western Front is an impossible success that somehow managed to exist. It is a Pre-Code film that glazes over nothing. It faces the harsh results of everyone within the story.

The film, for its time, was an absolute blood bath that shook all of the naive men who thrust themselves into war into submission. One of the main characters returns to warn the youth that they have no idea what they are in for if they were to sign up to fight, and yet we can only imagine that they will refuse to listen as well.

Around twenty percent of the special effects will feel dated, but the bulk of what you see is still impeccably pulled off. There are many different attempts at recreating the horrors of war, and all of them work. Call this anti-war propaganda if you want, but it is still a ground breaking film that is to be seen in order to be believed.

Classrooms are still showing this film to provide visual context for students, and thus its emphasis continues to live on. Even without the aide of the education system, All Quiet on the Western Front holds the distinction of being one of the prime War films.

3. Rebecca (1940)

Believe it or not, this is the only Alfred Hitchcock film to win Best Picture. While you let that sink in, you should also remember that David O. Selznick produced this feature after the gargantuan success of Gone With the Wind. The film only won the top prize and an award for its cinematography, as if none of the people in the film truly mattered. It’s true that Manderley is a character, as the mansion consumes everyone that enters it.

Like the images frozen in time on the mantlepieces in Manderley, Maxin de Winter and his unnamed new bride are chillingly unresponsive; they do not react like regular people. Rebecca is not your common marriage film, as it is inspired by the dreariness of anxiety one gets from having an untrustworthy partner.

Rebecca is one of Hitchcock’s closest feats to making a Noir film that isn’t Notorious. No one smiles widely, even when they are at their happiest. Death is an ongoing theme, as some welcome it and some are forced to desire it. This relationship is geared on the countdown to one’s demise more than it is based on the joys of the moments before the end.

Joan Fontaine and Laurence Olivier are a great couple of living wax figures, as Judith Anderson plays the human incarnation of Lucifer. Nothing about Rebecca will warm your heart, but it sure works as a glance into hell (both personal and literal).

2. It Happened One Night (1934)

Frank Capra is back on this list, and his screwball comedy masterpiece It Happened One Night remains one of the earlier films to show the world what Best Picture was really all about. Most of the films to win before this earned their awards (take that with a grain of salt if you will) for being voted the best film of their respective years.

It Happened One Night was one of the first to insist a legacy was to follow its paved road. It won the big five awards (Best Picture, Director, Actor, Actress, and Screenplay), and it deserved all of them. It Happened One Night is a chaotic team effort that is the movie version of a cat chasing a laser pointer’s dot.

This film is strewn with dramatic irony, as a chunk of the humour is what we can see and the characters cannot. Robert Riskin created a whole collection of dialogue queues with punchlines ready for battle, and they all get fired off with the precise timings of Claudette Colbert and Clark Gable.

This film may not be the screwiest of early comedies, but it is manic due to its characters’ misunderstandings and own personal motives. Love is strange, but so is coercing a runaway to get a good story. They just don’t make them like It Happened One Night anymore, as this film will likely last for eternity.

1. Casablanca (1943)

You know you have done something right when a word is more often associated with a film than the actual city it is named after. Two years before, Citizen Kane was snubbed by the Academy in favour of How Green Was My Valley. Because of this, Casablanca is the first Best Picture winner with an insurmountable script (even people who haven’t seen the film can recite most of the dialogue) and directing from the future.

Casablanca was well beyond its years; if you look at the other winners of the forties, most of the entries cannot even come close to what Casablanca pulled off. This is the textbook romantic war film that has been tried again and again and never bested.

Part of its success is because it is an examination of a love well after its expiration date, when Ilsa has moved on and Rick has nearly drowned himself to death in sorrow and alcohol. This was a love that was split to survive, and a test of what love means after a relationship is over.

Humphrey Bogart and Ingrid Bergman were such a tremendous duo here, that their names often bring us back to this film first before the rest of their respective filmographies. Their careers are nothing to ignore, either, but it is Casablanca that keeps bringing our attention back to this fact. This resembles the struggles of the characters, who can never escape their pasts despite what the second World War did to their love.

When lives are questioned, and the darkness is about to spill down the very street you stand on, is there enough time to be bitter about your separation? Casablanca stands the test of time as a romance film, because it just was a different take on the style. This film cannot be remade (even a colourization of the original was deemed vastly inferior), and we were lucky to be in that bar at that very point to witness this classic.

Author Bio: Andreas Babiolakis has a Bachelor’s degree in Cinema Studies, and is currently undergoing his Master’s in Film Preservation. He is stationed in Toronto, where he devotes every year to saving money to celebrate his favourite holiday: TIFF. Catch him @andreasbabs.