“An impressive achievement, often suggesting a weird expressionist blend of 2001, The Warriors, Blade Runner and Forbidden Planet… [Akira] is a towering achievement of imagination and the detail of each frame is a miracle of film artistry.”

– Geoff Andrew, Time Out

Come, Armageddon! Come!

An uncontested landmark of animation, Katsuhiro Ōtomo’s classic Akira also epitomizes the very summit of apocalyptic science fiction from Japan. Based on the sprawling thirty-two-volume manga––numbering an intimidating 2,000 pages!––written by Ōtomo, for all of its substantiality the plot is shrewdly simple.

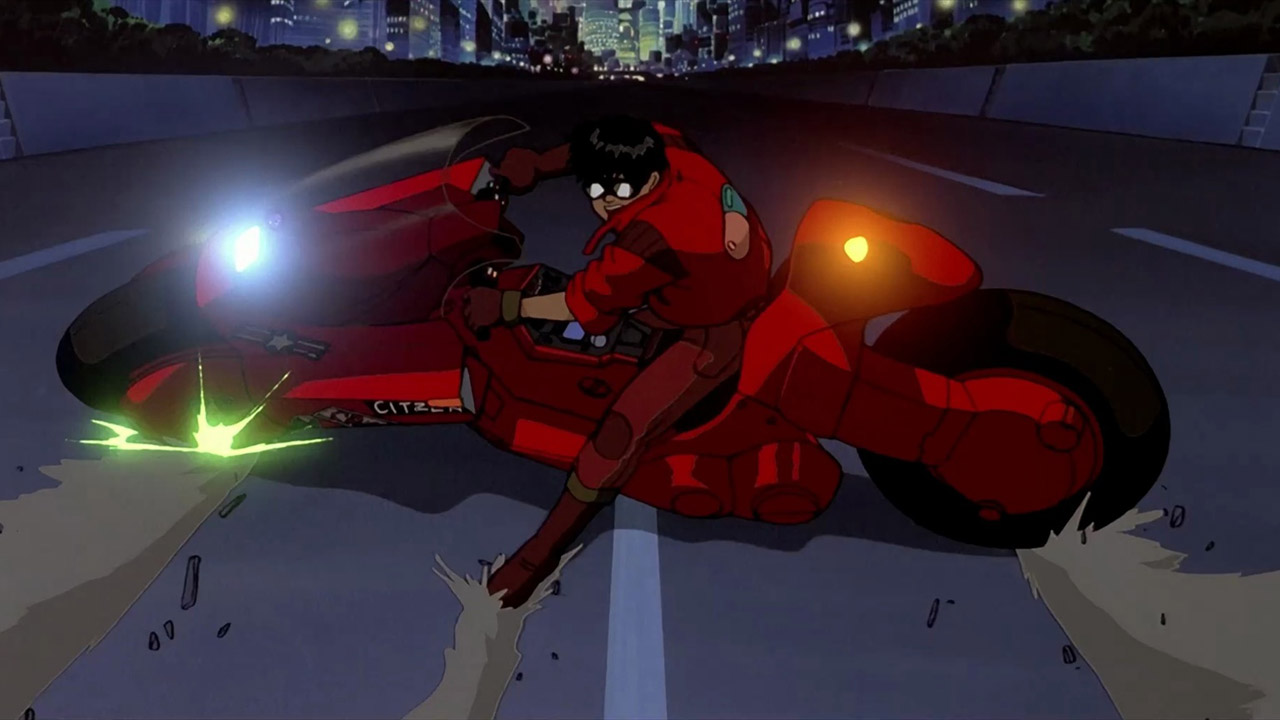

In the holy mess near future Neo-Tokyo––renamed after a late twentieth century waterloo wiped out much of the original Tokyo––finds teenage motorcycle gangbanger Shōtarō Kaneda uncovering some nasty business with his once best pal Tetsuo Shima, now transmuted into a bloodthirsty telepath with the efficacy and the inclination to commit mass destruction and murder.

Kaneda, grudgingly of course, coaxed by the nominal love interest of a young woman named Kei, joins a disparate group of anti-government “terrorists” searching for the cryptic Akira––a telepath even more forcible and perhaps even more frightening than Tetsuo.

It’s only teenage wasteland

Much of Ōtomo’s brilliance and a large part of Akira’s appeal lies within the linking of Armageddon with the angst and acrimony of the rebellious teenagers at the film’s heart. John Hughes this most certainly is not, but most certainly, as his warm fuzzy films of the same era often articulated, for a troubled teen every emotion and every upset certainly feels like the end of the world.

What Akira rather audaciously posits is that a telekinetically and psychically enhanced teen, whose super powers increase exponentially with his vulnerable emotional state, could become a belligerent, embittered, and hostile ticking bomb, quite literally.

Largely Akira is an electricity-rush of action adrenaline that left a huge mark on the world stage. Very few people, in North America especially, had seen a cartoon anything like this.

The massive production budget for the film was nearly $10 million––a record sum for a Japanese animated film at the time. The often balletic action sequences and set pieces, awash in color and constant motion and expertly edited to a startling musical score performed by Geinoh Yamashiro Gumi added immeasurably to Akira’s seductive sheen.

Beyond the beautifully detailed eye-confectionery Akira also offered some serious and sobering exploration of approximations, ideas, and anxieties that have long captured the Japanese psyche. Such eerie and obsessive designs as the country’s continuing ambivalence towards military capability, millenial malaise, and the real fear of social and societal collapse.

There ought to be clowns

Akira made good on a new promise to a new breed of audience experience; that of a deeply immersive and implicit story world where the hyper-detailed backdrop; philosophical and religious conjecture on the repercussions of technology on mankind as well the hyper-reflexive mental connections with other media content creates a layered checkerboard of possibilities and understandings for fans to lose themselves into.

Gone is an essential plot or narrative in exchange for this vast and varied sea of potential meanings. This experience was emblematized by what was dubbed “otaku”––essentially a new type of fandom.

With pastiches and permissions to samurai and martial arts films, to familiar fairytales, and superhero movies, to cyborg-addled sci-fi, film noir, and the burgeoning cyberpunk scene, Akira appealed and continues to appeal to so many.

“[Akira] is a landmark production that can be watched with equal satisfaction as a metaphorical psychodrama or as a sheer visual spectacular.”

– Tasha Robinson, The AV Club

We will become silhouettes

For myself, coming across Akira at a relatively tender age, it was easy to get swept up in a strange story seemingly fed and fueled by society’s irrational fear of its youth.

The tragic and terrifying Tetsuo Shima is the ultimate ticked-off teen; wild, intractable, and in revolt. He’s the one with enough power and competency to amass at cruel body count. And in opposition to him is the dark and Delphian Akira, whom both the army and the government have good reason to fear; for he’s at the heart of Tokyo’s earlier mass-extirpation.

Unlike Tetsuo, Akira is eternally fixed in an arrested development; that of a child. He signifies adolescence compelling destruction on a grand scale, one that echoes the atomic destruction that decimated Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the collective fears that have festered in the psyche ever since.

Japan’s fascination with annihilation goes beyond the playful pop culture pastime, extending beyond Ishirō Honda’s Godzilla and other resulting kaiju pictures, and with the film Akira goes the furthest yet into the scorched earth of Apocalypse. Like Kaneda’s souped-up blood red bōsōzoku this film takes us speeding headlong down a mad, dirty, and even sexy thoroughfare of accomplished and accelerating story. Akira is one hell of a fantastic trip.

Author Bio: Shane Scott-Travis is a film critic, screenwriter, comic book author/illustrator and cineaste. Currently residing in Vancouver, Canada, Shane can often be found at the cinema, the dog park, or off in a corner someplace, paraphrasing Groucho Marx. Follow Shane on Twitter @ShaneScottravis.