For thousands of years, art was inseperable with religion. Religion had full dominion over culture, so aspiring expressionists could only seek inspiration from approved doctrine. In Christianity it was blasphemous to create anything not already in the Bible; and in Islam it was blasphemous to create . . . well . . . anything.

Wonderful art came out of such constraints, of course, from the Sistine Chapel to Ben-Hur, and even Islam established its own art by finding ingenious workarounds to Sharia law like calligraphic renderings of scripture. There’s no denying the scope and beauty of theistic art, but atheistic art is not without representation.

Though just recently accepted into popular culture, atheist movies exist and are among cinema’s bests. We’re talking about films which harbor themes of unbelief or narratives that foster religious doubt. They occupy a much smaller cinematic niche than those religiously-inspired, but only on account of their infancy.

It’s incredible how recently atheism was vilified in western culture, and this animosity still remains in much of the world. To think that the simple acknowledgment of the nonexistence of something ostensibly nonexistent is a belief system worth castigating is ridiculous. Atheism is as much a belief as religion is evidence. It’s not even fair to call them opposites.

The following movies are made for the unbeliever, but the believer can still draw something of value from the wide-raging and well-executed themes. They’re not just lightning rods of disagreement, but objectively good films that would not look amiss on any other list.

Possibly worth noting, we decided not to include documentaries, because fiction is truer than propaganda.

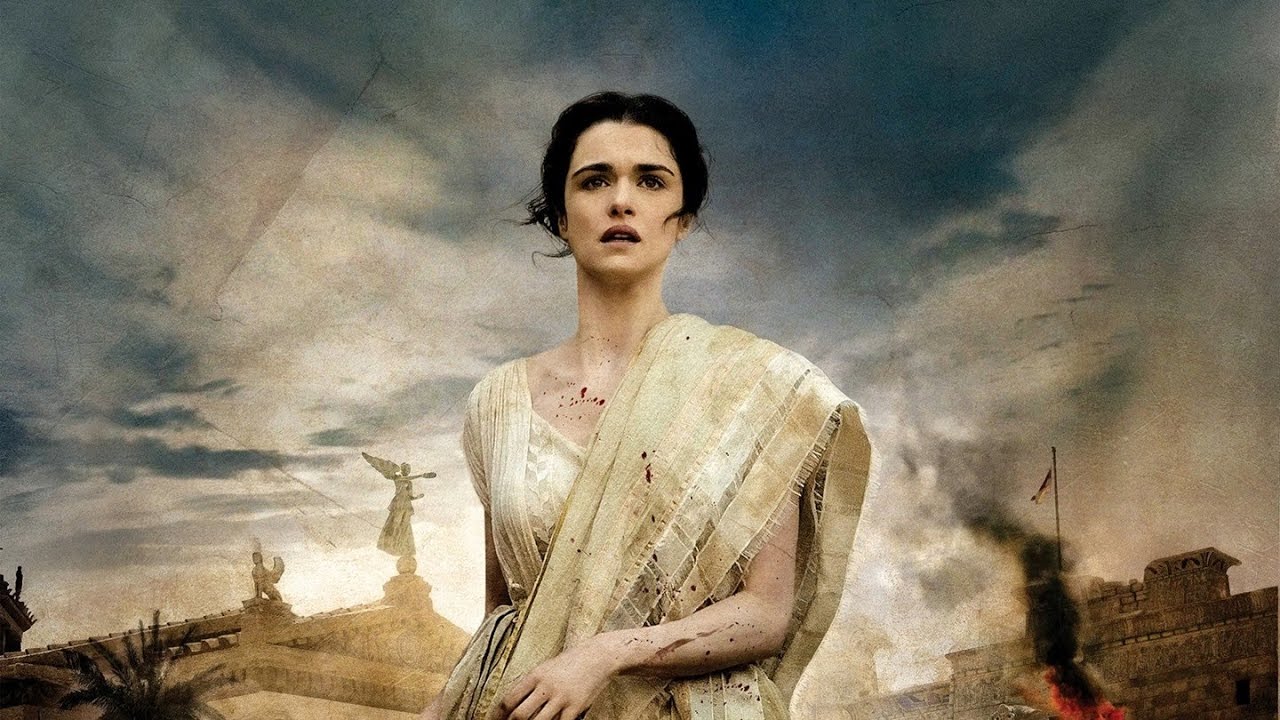

10. Agora

Set in Roman Egypt in the fourth century AD, Agora is a loose retelling of the Christian/Pagan conflict in a newly Christianized Rome. The centerpiece of this strife is Hypatia, a mathematician and astronomer, known, in reality, as a pioneering woman of science. The film takes a few liberties with her identity, however, portraying her, not entirely unfoundedly, as a rational unbeliever and sole sane person among murderous dogmatists.

While Christians, Pagans, and Jews are killing each other over religious differences, Hypatia is trying to understand the universe from a perspective devoid of celestial partisanship. Her curiosity seizes the motion of the planets, once believed circular and revolving around the Earth, but Hypatia discovers an outdated model of heliocentricity—planets orbiting the sun—and applies this knowledge to a new system.

This system combines the heliocentric model with elliptical rotations rather than circular, finding that the perfection of circles and man’s supposed centricity have no foundation in our universe. This cemented our current understanding of planetary motion, while also cementing Hypatia’s heresy.

Hypatia’s ideas, agnosticism, and power and influence in Alexandria threaten the Ecclesiastics, who cry witchcraft and have her murdered. She’s just one in a long line of thinkers whose lives were destroyed by religious persecution.

9. The Invention of Lying

It’s a reality where everyone tells the truth, until one person doesn’t, and of course religion is born.

Written and directed by comedy legend and atheist Ricky Gervais, The Invention of Lying may at first glance appear as a saccharine romantic comedy, but it contains some very important insights on human nature.

Ricky Gervais plays a screenwriter existing in this truthful—and consequently irreligious—world who discovers lying, and the outcome is predictably ridiculous. He gets the girl of his dreams, gets rich, gets away with all crimes, and can do literally anything he wants, as the one who lies holds all the power in the world.

Finally he becomes the Moses-like figure of his own religion, forged simply by the ability to lie with impunity. Guilt begins to plague him, however, especially in regards to his fiancée. After convincing the world all answers come from an invisible man in the sky, it’s the forsaking of heavenly dogmatism for personal choice that allows the only approximation of truth in the universe. He gives people the choice to be right or wrong. Despite the imperfect system, people are better for it.

Perhaps the most poignant part of The Invention of Lying is that religion is born out of the simple white lie of an afterlife told to Gervais’s character’s mother on her deathbed. It’s a hard fact to stomach, but shows that even the smallest and good-natured lies can have disastrous consequences.

8. The Sunset Limited

The Sunset Limited is a conversation between two theological adversaries: an atheist, played by Tommy Lee Jones; and a devout Christian, played by Samuel L. Jackson. The counterparts are basically forced into this philosophic stalemate after Sam Jackson’s character saves the atheist from suicide by way of the Sunset Limited, a passenger train in their home city.

The Christian takes the atheist to his apartment, hoping to save the man whom he believes is lost. However, the atheist has good reasons for his attempted extermination, and so an hour and a half debate unfolds entirely from the table of the dingy apartment.

Based on Cormac McCarthy’s play of the same name, The Sunset Limited is what dialogue aspires to be. The two go back and forth with convincing reasons for their respective positions. All points are measured and justifiable, and it’s up to the viewer to make his or her own decision on the meaning—or lack thereof—of life.

The ending helps push the viewer in the right direction. We won’t spoil it, since the film is more an than a narrative, but The Sunset Limited is on this list for a reason.

7. Contact

Atheism gets a bad rap for its perceived antipathy towards wonder; that rational thought is not conducive to any sense of greater beauty or amazement. Contact refutes this conjecture, demonstrating that science holds more wonders than religion can hope to contain.

The brainchild of Carl Sagan, the Patron Saint of Clear Thinking, Contact stars Jodie Foster as an astronomer searching for signals of extraterrestrial life. Finally discovering a radio wave sent from an intelligent being, Foster’s character is chosen to go in search of the signal’s source. What she discovers in the shuttle is beyond imagination, and beyond the imagination of the scientific community who cannot believe her story. Though she appeals, temporarily, to faith, her story holds true, and a whole new realm of scientific understanding becomes possible.

Contact is entirely secular, from beginning to end, with not one incredible event being construed as religious. Even the otherworldly revelations and surreal visions during the climactic “spaceflight” do not need any suspension of disbelief. What was seen is possible through superintelligence, and, despite all the fantastical occurrences, the astronaut does not dispute a universe that can make this possible without divine intervention.

6. Planet of the Apes

Everyone knows the story. In fact, it’s probably been beaten into your consciousness through endless remakes that seem to forget the profundity of the original, superior, entity. 1968’s Planet of the Apes is a goldmine of prescient themes, one being the acceptance of faith over fact.

Going reverse-chronologically, starting with the famous twist ending, Planet of the Apes shows our own world had apes become the apex species. The Apes have built a civilization far surpassing our own, but there are flaws, notably the same religious defects that weaken all advanced societies. They cling to sacred scrolls believed written by their god of Simian image and reject the substantial evidence of an ancestor whose slight genetic difference refutes the claim of divine creation on which the Apes’ entire being rests. Sound familiar? This simple role reversal proves effective satire by making our own creationist beliefs sound silly from the mouth of an ape.

While Planet of the Apes is not overtly atheistic in theme, the portrayal of a meta-Darwinian reality where apes evolved from transitional humans leaves little room for religious belief—besides, at most, deism.