Consumerism is the natural by-product of capitalism. Really, it’s the natural by-product of being alive: we all need things to survive, after all. Food, housing, clothing, from beginning to end it seems it’s our natural state to consume.

But living in a capitalist society also complicates the matter, particularly since in an affluent society there’s so much being produced and advertised to consume: cars, technology, entertainment, experiences—it seems like at the right price, everything’s for sale. Of course, this arrangement has found many discontents, and in film especially the consumerist lifestyle is ripe for satire (which is ironic, considering that films themselves are consumer items).

Whether providing dark commentary on the dangers of consumerism, cynical denouncements as to the state of capitalism and consumerism, or even celebrating the sheer volume and luxuriousness it provides, if you live in a capitalist nation, you’re heavily encouraged to engage in consumerism—it’s simply inescapable. It’s also worth taking a closer look at to consider the ramifications of it on both a micro and macro level. With this in mind—and gratis–here are 10 great movies about consumerism.

10. Trading Places (1983)

The world could easily be divided between to types: the haves and have nots. Those that have live comfortable lives shielded from the ugly realities of poverty, while those that don’t are trapped in cycles of unemployment, substandard living conditions, and frustrated ambitions. 1983’s Trading Places takes this idea and runs with it, making a comedy out of the idea of whether nature or nurture determines a person’s place in this world.

The wealthy, powerful Duke brothers make an arbitrary bet with each other along these lines, choosing the well-heeled managing director of their brokerage firm, Louis Winthorpe III (Dan Akroyd), and street hustler Billy Ray Valentine (Eddie Murphy), to trade places in life to prove this point. Winthorpe is framed as a thief and philanderer, becoming disgraced and losing his fiancée, job, and house in the process, while Billy Ray is handed Winthorpe’s old life.

While Winthorpe struggles on the bottom rung of society, saved only by the kindness of a prostitute (Jamie Lee Curtis), Billy Ray quickly learns the brokerage business and quickly adapts to a better standard of living. But he overhears the Dukes’ plan to return him to the streets now that their bet’s been settled and he seeks out Winthorpe to turn the tables on them

A humorous look at both sides of life in a consumerist culture, Trading Places smartly identifies how social status, class, and materialism shapes the reality of one’s life in the US. While Winthorpe is initially depicted as a snob that looks down on others due to his well-appointed home, lavish wardrobe, and superficial status symbols, once he’s stripped of all of these trappings he becomes as desperate and pathetic as those he once viewed with contempt.

Similarly, Billy Ray almost instantly adapts to the material goods and elevated social status handed to him, significantly changing as a person as a result. A wry look at the dramatic effects consumerism and materialism can have on changing perceptions, Trading Places is a comedy that hits its satiric mark a little too close for comfort.

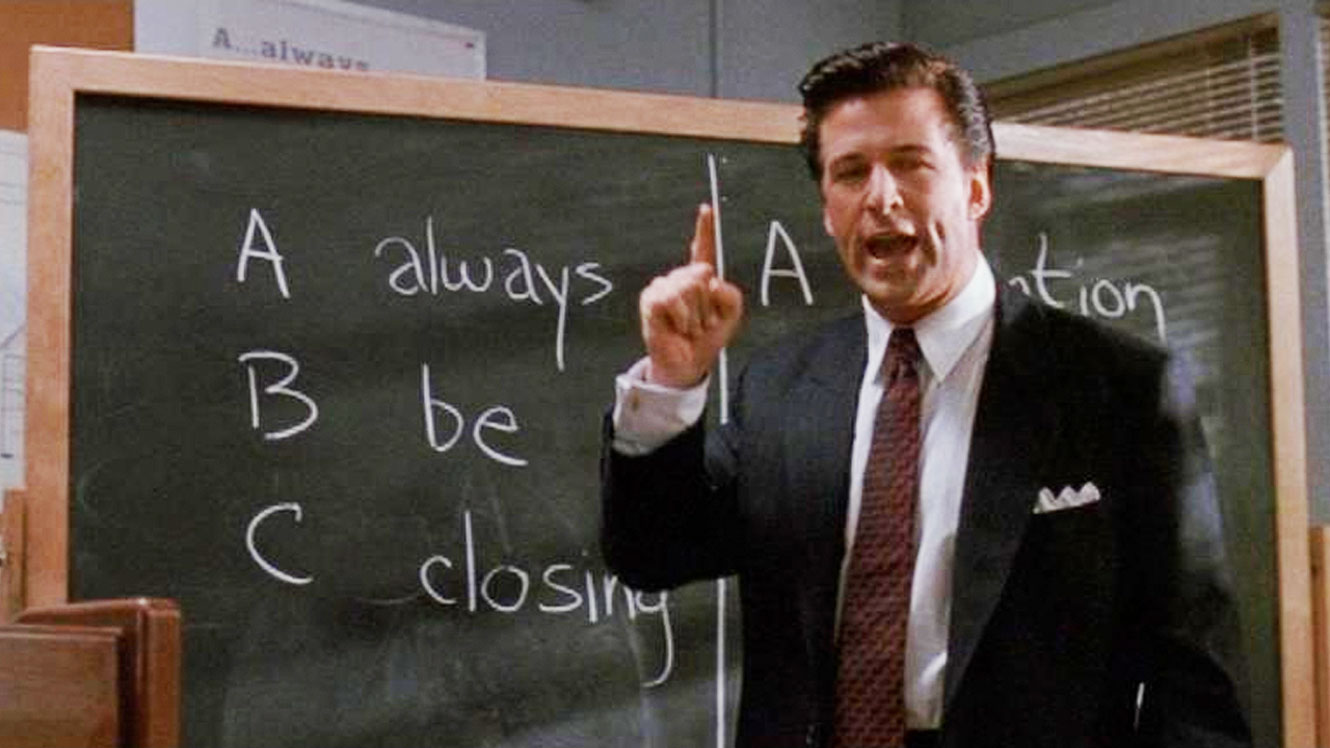

9. Glengarry Glen Ross (1992)

Money is at the heart of consumerism, and capitalism is the engine that makes it all run. While trading services for money is a common way people make a living, sales is the direct approach. But direct sales and making a commission from the amount sold is a difficult way to make money, and it’s often a competitive and ruthless business.

The characters in Glengarry Glen Ross know this all too well: focusing on four real estate salesman who have been given warning that all but the two top salesmen will be fired by the end of the week, the men use the leads given to them to wheedle, manipulate, and outright lie to potential prospects to sell the land of real estate developments. Laced with profanity and detailing the desperation all of the men have as they grasp onto the only jobs the know, Glengarry Glen Ross is a dark look at how the machine of capitalism pushes people to emotional extremes just in order to survive.

Consumerism covers the micro and macro of financial transactions, and Glengarry Glen Ross is an examination of the psychology of selling to consumers—in this case, real estate, but it represents any purchasing arrangement between the sales person and the customer. The salesmen deceive their prospects, their co-workers, and even themselves all for the end goal of receiving money for a product. Whether the customer wants—or even needs—the product is beside the point.

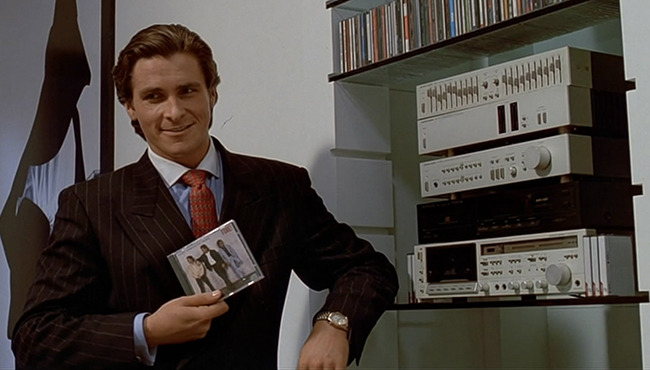

8. American Psycho (2000)

While 1987’s Wall Street tackled the financial industry as a profession, 2000’s American Psycho focused in on what kind of person such a profession produces—in this case, a psychotic, vain narcissist named Patrick Bateman. Set in the height of the go-go 80’s, Bateman lives an immaculately materialistic life, complete with chauffeured cars, expensive clothes, meals at the chicest restaurants in Manhattan, and a tony apartment. He works in finance in a do-nothing job and, as his inner monologue states throughout the movie, despises nearly everyone in his life.

American Psycho is a pristine representation of consumerist culture in America, replicating the rampant conspicuous consumption—and the rather soulless materialism—that defined certain segments of society in the 1980’s. Bateman can list off brand names, items he owns, and music he likes without hesitation but becomes frustrated when he has to articulate his feelings–and a homicidal maniac.

He’s a living representation of how blind consumerism—in short, buying and owning stuff—does not a person make. Writer Bret Easton Ellis has said he based the character of Patrick Bateman on his own life at the time, which he described as “slipping into a consumerist kind of void.” Viewers will only find a void at the center of Bateman, who at first seems to by a murderous psychopath, but by the end of the movie turns out to be the victim of a hollow lifestyle that looks fantastic on the surface but only runs skin-deep.

7. The Wolf of Wall Street (2013)

Much like 1987’s Wall Street, The Wolf of Wall Street is about one thing: money. Specifically, how to make a crazy amount of it and what a fun, great life it will buy you. Jordan Belfort (Leonardo DiCaprio) smugly provides the audience with a tour of his life, starting out as a scrappy, ambitious broker and ending with an arrest for fraud by the Securities & Exchange Commission.

Along the way, he amasses a large fortune through unethical trading practices, which he uses to fund a debaucherous lifestyle that includes a healthy drug habit, scores of prostitutes, and owning estates and a luxury yacht. And the worst/best part about The Wolf of Wall Street? It makes his life look like a lot of fun.

Belfort is an unapologetic capitalist that is ultimately addicted to money: as he sees it, money is the key to unlocking the universe and all that it has to offer. He has a beautiful wife, lives an incredibly comfortable life, has insane adventures while high out of his mind on drugs, and outside of getting divorced and having to serve three years in a minimum security prison, walks away from the entire ordeal more or less the same as he was at the beginning.

Consumerism is fueled by capitalism, and The Wolf of Wall Street demonstrates just how amazing one’s life can be if they have enough money in a consumerist society. Sure, it’s an immoral, shallow, and dangerous life, but it does look like a lot of fun.

6. Network (1976)

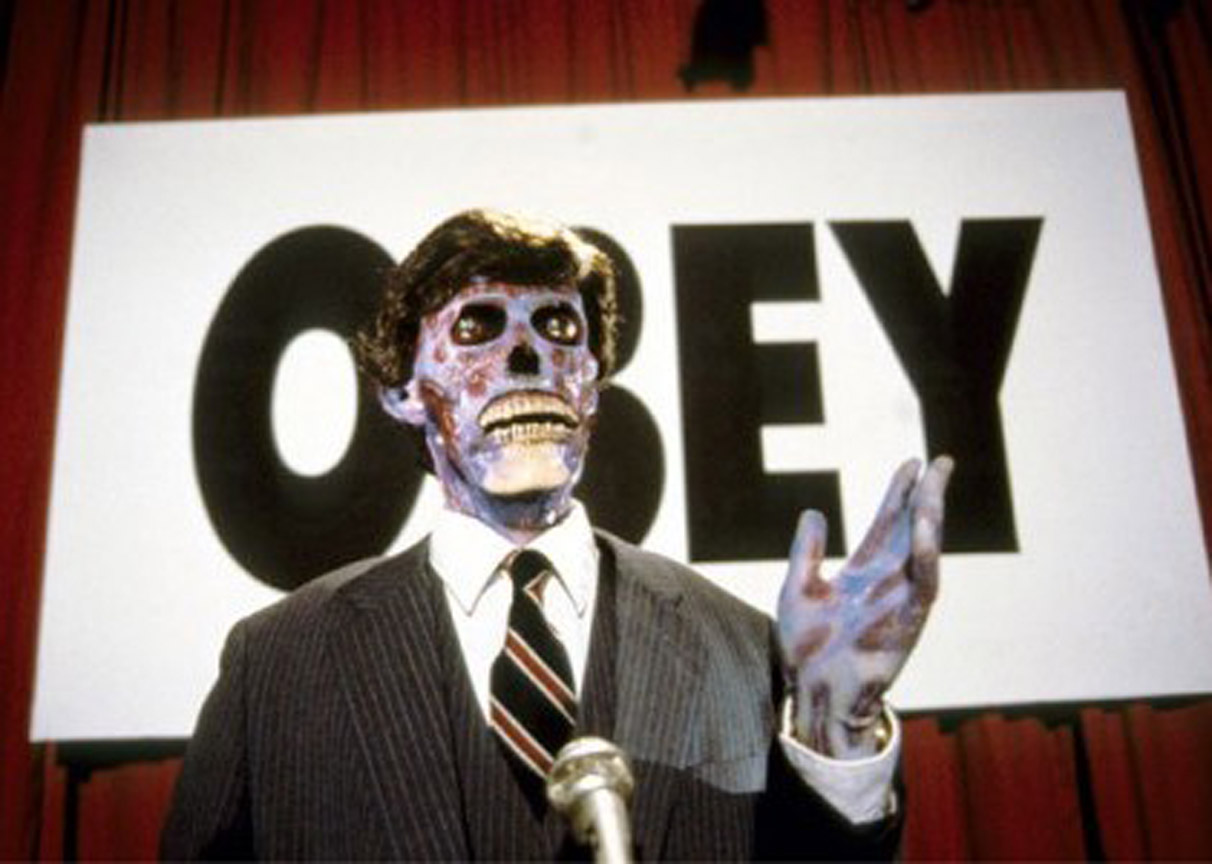

One of the first and best films about the power of media and its ability to shape perceptions of a mass audience, the core of 1976’s Network is sometimes forgotten by audiences today. But what it says about consumerism and large corporations’ dependence on the population to engage in consumerism is even more prescient now than ever.

When longtime news anchor Howard Beale snaps during a broadcast of the news on live television, the network he works for cynically exploits his obviously troubled mental state for ratings, allowing him to rant on the broadcast what he finds wrong with the world. While this initially is good for ratings, to the point where he’s given his own show, his bosses at the network—who are representative of the larger corporation that owns the network—sit him down for a little talk.

The monologue delivered by the chairman of the large corporation that runs the network, Arthur Jensen (Ned Beatty), is a damning piece of work that rips apart the truth behind the purpose of large corporations and their relationship to the common man.

In particular, after stating that there is no America or democracy, but just corporations, he lays down this unsettling truth: “The world is a collage of corporations, inexorably determined by the immutable by-laws of business. The world is a business, Mr. Beale; it has been since man crawled out of the slime.” He then orders Beale to explain to the public how the world now works, and how they should go along with it because it’s in their overall best interest.

Network speaks a lot of truth about a number of disquieting issues in the modern world: the power of media outlets, the disintegration of society and subsequent apathy of the populace, and how easily society can be deceived by a box with flickering lights. But perhaps its most subversive ideas come in that one speech, where a very powerful man in charge of a very large and powerful corporation breaks down how human beings are little more than consumers that depend on corporations—and that this is the natural order of the universe, whether we like it or not.