5. The Deer Hunter (1978, Michael Cimino)

Along with provocateurs like Sergio Leone and Stanley Kubrick, the late-Michael Cimino also belongs on the mantle of one of cinemas greatest mavericks. His desire and urge to constantly push the envelope of what film can produce started small with Thunderbolt and Lightfoot (1974) and ultimately climaxed with the infamous Heaven’s Gate (1980), the film famous for being so monumental in scope and vision that it single handedly tanked Hollywood big-budget romanticism. In between these titles he made The Deer Hunter, an everlasting ode to love, loss, and sacrifice.

The film follows the exploits of Michael (Robert DeNiro) and his friends, at first in an industrial town in Pennsylvania, then in the rice paddies of Vietnam. At home, Michael, Nick (Christopher Walken), Axel (Chuck Aspergreen), Stan (John Cazale), Steven (John Savage), and John (George Dzundza) prepare for Steven’s wedding. They drink, sing “Can’t Take My Eyes Off You,” wish their friend best of luck when he whisked away by his mother, and at the conclusion of the ceremony, we find that Michael and Nick are the outliers of the group.

Both natural leaders, they are obviously destined for greater things. When the friends go off into the mountain wilderness for one last deer hunt before Nick, Michael, and Steven are shipped off to Vietnam, the bonds of their friendship are exemplified. When they enter Vietnam, however, they will never be the same.

Tortured, beaten, and held prisoner as soldiers, Michael and Nick must engage in a head to head game of Russian roulette. They are pushed to their limits, Steven already having lost his mind, and must risk death in order to escape. When they win the game and kill their captors, Nick manages to get away on a helicopter, but Steven and Michael get left behind. At a medical center, Nick, clearly damaged from his experiences, runs off and finds himself joining a group that use Russian roulette as a means of gambling, whereas Michael and Steven find allies and manage to return home.

The rest of the film encapsulates Michael’s readjustment to home and his new budding romance with Nick’s girlfriend: Linda (Meryl Streep). Michael is damaged from his experiences and grows weary after Nick is still missing, but when he is called to return after a lead on his whereabouts, he promptly goes back for his friend. Now back in Vietnam, Michael manages to trace Nick to the roulette tournament.

Entering himself in order to rescue him, we find that Nick is thin, worn, haggard, and gaunt. He is no longer the same man we knew. At their final conclusion, Nick puts the pistol to his head and pulls the trigger, killing himself, leaving Michael heartbroken and shattered. The film ends with Nick’s funeral, and his friends melancholically singing “God Bless America.”

4. Across 110th Street (1974, Barry Shear)

Blaxploitation is the ethnic subgenre within exploitation cinema. Having primarily come into being during the 1970s, Blaxploitation films were made more specifically for the urban black audience within the United States, despite its popularity across ethnic and cultural boundaries.

More often than not, these films provided a unique social commentary on the black experience in contemporary society, implemented through stories of revenge, love, loss, violence, and corruption. However, whereas some of these films proved to be unrelenting commentary with an entertaining conclusion, some opted for cold, bitter endings. Across 110th Street is one of these films.

The movie itself is set in Harlem along an informal boundary line: 110th Street. After the murders of seven Italian mobsters in the robbery of $300,000 from a Mafia-owned Harlem bank, a by-the-book African-American Lieutenant William Pope (Yaphet Kotto) has to partner up with the racist but streetwise Italian-American Captain Frank Mattelli (Anthony Quinn) in order to find those who perpetrated the crime.

This pairing of two men with two radically different ideologies proves to be tumultuous at first, full of tension and racial dynamics, leading us to question whether or not this team can pull off the search. Throughout the film, however, despite the clashing cultures of black and white officers, Mattelli and Pope grow closer, forming a short-lived bond, overcoming their differences.

At the conclusion of the film, when the final criminal is caught and all is won, a single shot hits Mattelli. The film ends with Pope and Mattelli clutching hands, with no final resolution. This bond that seemed to be forming gradually between different personalities is broken.

3. Waltz With Bashir (2008, Ari Folman)

Air Folman’s masterpiece of the dynamic experience of memory in the wake of great tragedy and repression serves as a poignant representation of our ability to survive in tumultuous circumstances. It also builds steadily to an extremely cathartic climax that leaves the viewer awestruck in a sardonic stupor.

The film starts in the year 2006, where Ari meets with a friend from his service in the Israeli Defense Force (IDF). Meeting him at a bar over a few drinks, the friend tells him of several nightmares that he’s been having that are connected to his experiences from the Lebanon War in 1982. Having fought in the war himself, Folman is surprised to find that he recalls absolutely nothing from his experiences.

Later that night while driving home, he has a psychotropic vision from the night of the Sabra and Shatila massacres, the reality of which he is unable to clearly recall. In his memory, he and his compatriots are swimming in the ocean, walk from the water, done their uniforms and weapons, and walk into battle under the light of flares igniting overhead.

Folman then rushes off to meet a childhood friend and psychologist, who, upon hearing Folman’s apparent amnesia, explains memory’s inherently dynamic trait. It is alive in the sense that it can be repressed, manipulated, and, more importantly, recovered. The friend advises Folman to look for others who served with or around him in order to better understand what happened during his wartime experience. The subsequent film is Ari Folman’s therapeutic re-experiencing of what he had apparently repressed.

Throughout his journey, Folman interviews friends and other soldiers who served in the war. During these retellings, the animation of the film is cartoonish and entirely separated from reality. The visions and fantastical imagery ultimately personify Folman’s idea of “living memory” as well as directly exemplifying attempts at compartmentalizing these events.

Folman eventually realizes that he was not among the first line of soldiers attacking. Rather, he was stationed as support for the main attack force. He was stationed outside the main garrison surrounding the Palestinian refugee camps of Sabra and Shatila, where the carnage itself was perpetrated. Folman discovers that he was among those soldiers firing flares into the sky to illuminate the refugee camp for the local ally militia perpetrating the massacre inside.

Much like those who enabled concentration camps during the Holocaust, Folman helped indirectly perpetrate the massacres. That was what he was repressing: his collusion. The film ends with the animation dissolving into actual footage of the aftermath of the massacre, leaving the audience to watch in shock as real archival footage of the dead and screaming pervade the screen.

Much like a photographer’s camera is used to maintain a degree of separation, Folman takes away our proverbial camera (the animation and fantastical imagery), leaving us to contemplate the horrors with which he initially repressed.

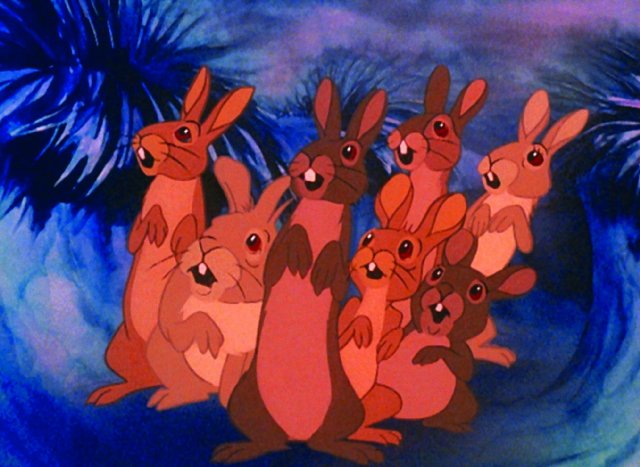

2. Watership Down (1978, Martin Rosen)

In Martin Rosen’s 1978 film, a rabbit named Fiver has an apocalyptic vision of their home getting destroyed. As a result, he goes with his older brother Hazel to beg the chief to have their home evacuated, but the elder doesn’t believe them and dismisses them.

As a result, the two form a group and attempt to make the flight themselves. Together, they travel through the dangerous woods, ford a dangerous stream, and after several other dangerous situations (leading to the deaths of a few others in their group), Fiver finally leads the group to the new home hill he envisioned called: Watership Down. Here the rabbits settle in, electing Hazel as chief.

All is not well in the land, however, when reports of a hostile warren reach Watership Down. A fellow resident, Holly, who encountered the new warren previously, begs them not to go there, describing it as a totalitarian state, run by incredibly unfriendly rabbits. By the end of the film, Watership Down is compromised by this group, and when they begin to attack, Hazel and Fiver ensure the warren’s safety through the use of a violent dog.

Several years later, Watership Down is thriving and an elderly Hazel is visited by death, who invites him to join him, assuring him of Watership Down’s perpetual safety. Reassured, Hazel accepts and dies peacefully, transitioning from this world into the next.

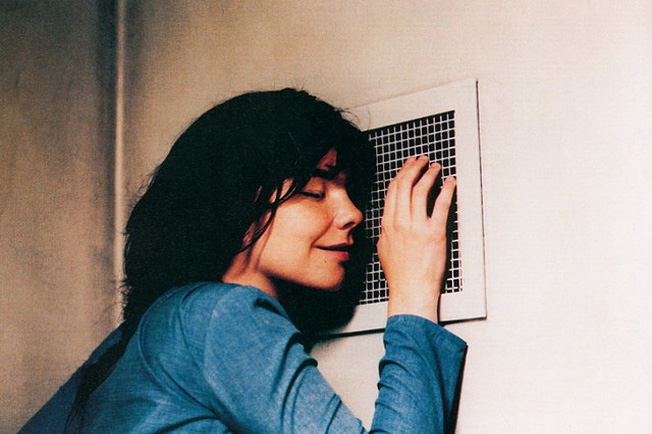

1. Dancer in the Dark (2000, Lars von Trier)

If there is one modern auteur who continually seeks to expose and expand the envelope of audience manipulation, it is most certainly Lars von Trier. This controversial nonconformist is renowned in the cinematic world, whether it be through his Persona Non-Grata personality at Cannes, severe history of drug abuse, or, most notably, the often off-putting, yet extremely provocative, imagery of his films.

However, whether or not you come to admire or hate his pictures, when it comes to filmmaking, Lars von Trier is undeniably pure innovation, intellect, and art. Consistently, Lars von Trier has sought to subvert, reimagine, or, in the case of Dogme 95, create genres. His 2000 film “Dancer in the Dark” took the music genre and, in an almost meta-analysis, transformed it into something of his very own.

The film follows the life of Selma Jezkova (Bjork), newly emigrated from Czechoslovakia with her son Jean, now living in 1964 Washington state. We enter the story with Selma rehearsing for her role as Maria in a community arrangement of “The Sound of Music,” singing and tap-dancing in step. Immediately, Selma is characterized as a classically romantic heroine, with a deep affinity for musicals and song.

Outside of the stage, Selma lives an impoverished life, working long hours at a sheet metal factory with her friend Kathy (Catherine Deneuve). After hours, she arranges hair pins for extra money at her rented home, under the caring eye of her landlords Bill (David Morse) and Linda (Cara Seymour). As the story continues, we discover that Selma suffers from a degenerative eye condition that will inevitably end in the complete loss of her vision.

The reason we see her working long hours is to save money to pay for an eye operation for her son, so he will not suffer the same fate as she will. When Bill finds out about her stash of cash, in desperate need of money himself, he steals the money.

When confronted, Bill makes Selma shoot him, and she is subsequently charged with his murder. She goes on trial, is subsequently found guilty, and put on death row. When she is told that she can escape her fate, she opts to insist that the money she saved go to her son’s operation. The finale of the film is her death, executed by hanging.

What sets this film into the musical category is that whenever things get too dull or distressing for Selma, she slips into daydreams where she imagines the people in the situations she finds herself in bursts sporadically into elaborate musical numbers. It gives a whimsical, innocent quality to Selma’s character, more childlike in performance, but so absolutely loving. She isn’t seen as an intrusive, helpless character, but rather, pure and completely blameless for any wrongs that occur around her.

Lars von Trier established her character in an absolutely virtuous sensitivity so that when it comes time for her martyrdom, our hearts are shattered at the outcome of her death. Another thing that makes it so downright depressing is the film’s lack of closure on Selma. In his previous film (the first of the Golden Hearts Trilogy) “Breaking the Waves,” the sacrifice of Bess was blanketed by the fact of a guarantee of a happy, bitter-sweet ending, in that her death still came with hope despite everything. In Selma, we just get the demise of a woman with a golden heart and only that.