6. The Levitation (Solaris, 1972)

The Levitation scene in Tarkovsky’s sci-fi art film “Solaris” sets a perfect example of the late Russian director’s talent to combine different art forms – music, painting, sculpture, and choreographies – and integrate them to cinema. For this scene, the evocative works of Bruegel, Bach, and Plato not only complement the theme’s allusion to humanity as a virtue lost to civilization, but as literal works of art that provoke emotions and revelations to the characters.

The scene’s mise-en-scene is set in a circular room whose woodwork and gallery décor contrast with the metal and aluminum artifice that dominates the ship’s design. Its walls are adorned with several paintings of Bruegel’s “The Months” collection. Particularly, the snowy hillside of “The Hunters in the Snow” calls Hari’s (Natalya Bondarchuk) attention, being a human duplicate, and reminds her of a home video showing Kris as a child standing by a snowy landscape.

Bach’s “Prelude” underscores and supplements the elation of the weightless embrace between Hari and Kris (Donatas Banionis). Additionally, the Plato sculpture’s prominence in the frame echoes the Platonic concept of an illusory duplication derived from an ideal form, which is awfully similar to the dichotomy between Kris’ reality and Solaris’ fantasia.

During the lapse of levitation, the camera’s cut to particularities of Bruegel’s “The Hunters in the Snow” casts the impression of an emotional connection between individual and art. Through the association between Hari’s memory and the painting, the female human replica transcends to a deeper sense of being that, like the weightlessness of levitating, suggests an emotional synchronization between herself and her lover.

7. Monkey’s Telekinesis (Stalker, 1979)

This scene’s significance does not only derive from the supernatural powers the Stalker’s daughter wields, but how enigmatic its meaning is in the context of the film. Technically a one-take shot, this scene introduces Monkey reading and then reciting Fyodor Tyutchev’s poem “Dull Flame of Desire.”

Both the lack of lip-sync and the fact that she recites the poem after closing the book, suggests that the child relates the poem telepathically. It is unclear whether it was out of boredom or ennui, but Monkey puts her head on the table and using telekinesis, moves three drinking glasses across the table.

The fourth movement of Beethoven’s “Ninth Symphony” plays shortly after (in the film’s original version) a passing train provokes the walls and the ceiling to shake, but Monkey remains unmoved. The disturbance gradually subsides as the camera once again moves closer to Monkey. Through this motion, Tarkovsky subtly places emphasis on what the child is and how she feels about herself, rather than her supernatural powers.

For his final scene, Tarkovsky merges both the real world’s monochromatic sepia tone and the Zone’s colorful greenery to present a marriage between reality and the fantastic. Similarly, Monkey’s (Natasha Abramova) “mutation” seems to represent a union between the notion of the “physical” and the “spiritual” that until this point, the Stalker, Writer, and Professor aimed to penetrate, but ultimately chose to give up.

Therefore, this scene should not be interpreted inside the confines of morality, but as a sign of new perspectives, unknown possibilities, limits to be discovered, and altogether, change.

8. Rublev’s Frescoes (Andrei Rublev, 1966)

There are many compelling scenes in Tarkovsky’s black-and-white biography: the raid, the ringing of the bell, the witch’s persecution. But if there is one that stands out (literally) from the rest, it is Rublev’s frescoes during the film’s epilogue.

In contrast to the monochromatic tone consistent until this point, these colorful paintings document not only a brilliant artist’s vision, but more significantly, how art is rooted in an individual’s hardships, relationships, and observations.

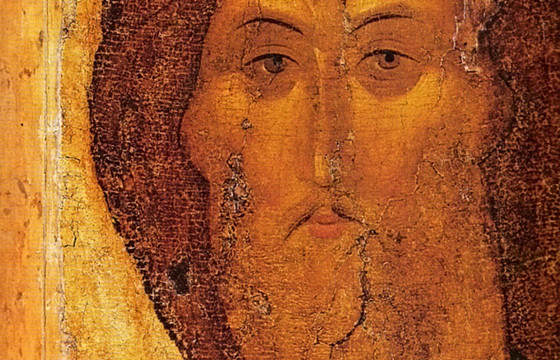

Breaking his vow of silence, Rublev (Anatoly Solonitsyn) consoles a sobbing Boriska: “You will cast bells. I’ll paint icons.” The camera then delves to a nearby dying ember before the frame fades into the icons. The scene then unfolds in a series of camera pans, tilts, and zooms, each focusing on the faces, rites, and other particularities of Rublev’s brushwork, but never a full view of the paintings. In effect, there is a degree of immersion to be appreciated in these close interactions with works of art.

There is a great deal of catharsis as the camera pulls back on the last of Rublev’s paintings, “Christ the Redeemer,” while composer Ovchinnikov’s score dissolves to a soothing rain (reminiscent of the last shot of “Nostalghia”). Through the last image – the horses under the rain, a Tarkovskian motif that symbolizes life – “Andrei Rublev” transcends the biographical exposition of the eponymous artist, and presents a purely cinematic representation of an individual’s need for artistic expression.

9. The Carrying of the Candle (Nostalghia, 1983)

“Display an entire human life in one shot, without editing, from beginning to end, from birth to the very moment of death.” According to Russian actor Oleg Yankovsky, this is what Tarkovsky proposed during their first meeting for “Nostalghia”.

This uncut shot is over nine minutes long, and it consists of Yankovsky’s Andrei Gorchakov’s repeated attempts to carry a candle across an empty mineral pool. By the third attempt, Andrei is successful in putting the candle at the edge of the pool before he collapses and dies.

Tarkovsky ordered tracks to be built on the ground for the camera to track and get closer to Andrei the nearer he gets to his destination. The particularities of the background – the stonewall, the pool’s frontage, and the moss – are incredibly well detailed and enriched with different dimensions. Giuseppe Verdi’s musical setting, “Requiem,” plays as Andrei expires, and the image remains focused on the candle alone, burning.

In terms of motives, Tarkovsky intended the scene to be emblematic of life’s cycle: birth, growth, and death. Both the one take and its length encapsulate the notion of an individual’s lifespan as well as the passage of time.

Similarly, Andrei’s hand covering the fire from the opposing wind is tantamount to the endurance of hardships throughout a lifetime. One could say that in this scene, Tarkovsky is able to remove abstractions of symbolism in order to depict the essence as well as the trajectory of life in just one motion.

10. Burning Barn (The Mirror, 1975)

Poetry. Long takes. Time distortion. The juxtaposition of water and fire. From the dacha’s introduction to the framing of a barn set aflame, this scene epitomizes the Russian director’s overarching themes through sheer visuals and lyricism.

Technically consisting of only five shots, this scene starts off with a pensive Maria (Margarita Terekhova) walking toward her house, a beautiful wooden cottage set under dusk’s orange dim light. Intended to be a recreation of Tarkovsky’s childhood home, the camera pans to reveal the dimensions as well as the idiosyncratic corners of his home replica.

The open windows allow the appreciation of rare visual contrast between the outdoors’ greenery and the vibrant orange from the wood and candles. Until this point, Arseny Tarkovsky – both a prominent Russian and the director’s father – underscores the scene with verses about remembrance, grief, and fate.

However, what is most memorable is the powerful imagery conveyed through verisimilitude and time distortion. In the last shot’s tracking motion, instead of immediately following the actors straight to the disturbance, Tarkovsky’s camera levitates on unoccupied spaces, falling bottles, and a mirror’s reflection, all in order to invoke emotion and familiarity rather than conceptual interpretations.

Particularly, the camera’s unorthodox framing and motion reveals a blurred but vibrant image that, once focused, turns out to be an old mirror’s reflection of the two siblings staring at a burning barn. The hues of orange and yellow set against the blue glare through the doorway, and the angle of the mirror in relation to the camera, creates an illusory image that feels otherworldly, even for Tarkovsky.

The final image features a strong composition: Maria, a second individual, and the Tarkovskian surrogate boy, standing on the foreground and in center frame, the barn as it is consumed by fire. Accompanied by the light rain and the sound of droplets, this image unfolds as an oneiric trance that is as mesmerizing as it is thought provoking.

If Tarkovsky’s enigmatic autobiographical film is about an individual’s recollections, fantasies, and memory fragments in relation to his closest relatives, then this scene visually encompasses its strongest elements: nostalgia, childhood naiveté, young mothers, and the mirror as literally a refraction of memory.