5. The War of the Worlds (1953)

When it comes to 50s sci-fi, George Pal’s and Byron Haskins’ The War of the Worlds rides quite high in regard. Two years in the making and an Academy Award winner for special effects, this classic atomic age take on Wells’s most famous novel swaps sleepy Woking for California and towering tripods for swan-shaped vessels.

The emphasis on “War” is indeed felt, as the opening monologue reminds us of previous 20th century warfare; followed by the film’s almost exclusive focus on the militaristic/scientific efforts to combat the invaders.

Quite loyal in its setup, these aliens crash land in the American countryside and emerge in their threatening war machines. Gene Barry and Ann Robinson star as two scientists desperately aiding the US army for a way to stop them, only to fail at every turn.

Along with screenwriter Alfred Edgar, the actors do an admirable job at grounding the film with some decent characterization, in what otherwise could have easily become an effects heavy, impersonal war film. Specifically Barry, whose scientific authority and leading man presence anchors the film nicely.

For any serious H.G. fan though, it still may leave much to be desired. Perhaps a result of stricter censorship, most of the novel’s grislier elements are unfortunately absent. The red weed, the poisonous black smoke, and the vampiric nature of the Martians are all regretfully missing. The design of the Martians in fact, conjures thoughts of E.T rather than anything scarcely intimidating. Yet this, along with the copper-plated Martian ships, amounts to a quaint charm possessed by so many films of the era, and is virtually impossible to dislike.

Sandwiched in time between Orson Welles’ controversial radio play and Jeff Wayne’s spellbinding musical, The War of the Worlds is fortunately still recalled as a solid sci-fi classic. Like Spielberg’s effort 50 years later, it nicely updates the story to its own era and arguably fronted the first wave of classic alien invasion movies, as well as establishing its own mini-franchise – spawning merchandise and even a short-lived TV series in 1988.

4. The Passionate Friends (1948)

An underappreciated gem in the eclectic filmography of the peerless David Lean, The Passionate Friends is sourced from Wells’ equally overlooked 1913 novel, telling of a love story laced with ideas of social reform. Anne Todd risks her secure and comfortable life with respected husband Claude Rains, after rekindling her passionate romance with university professor Trevor Howard.

The film exceeds as a dramatic piece, and proves its superiority by avoiding the story pitfalls fell into by lesser dramas. For example, Lean never manages to totally vilify one of his central characters. Despite occupying opposing roles in the story, each character in the aforementioned love triangle is equally relatable and sympathetic, aided in no small part by great performances from the actors. Lean regulars Todd, Rains and Howard emotionally enrich and heighten the picture, supplying their characters with the sufficient depth and affability to make for a thoroughly involving quarrel.

Along with character strength, the film keeps up a nice narrative intrigue through structure. Despite utilizing flashbacks (and occasionally flashback-within-flashbacks), while dealing out equal screen time to each lead, the film never gets convoluted; it rarely loses pace, and smoothly maintains a strong focus on the dramatic matter at hand.

Flashbacks incidentally, were also used as a storytelling tool in Lean’s earlier masterpiece Brief Encounter, and fans will no doubt recognize their various similarities. Lean returns to similar themes of infidelity, guilt and temptation, as well as including Trevor Howard, a motif of trains, and even a similar ending, where both are similar in terms of subject and even blocking. The film’s climax incidentally, is one of the more drastic changes from the novel and may leave Wells enthusiasts rather torn.

Otherwise, The Passionate Friends is still one of the best offerings of his work. While it rarely betters films like Brief Encounter in terms of technique or emotional effect, it mostly certainly deserves a higher place in the history of cinema, both in regards to Lean’s work and to other Wells cinematic efforts.

3. The Invisible Man (1933)

Disappointed with the liberties taken by Paramount’s The Island of Lost Souls, H.G. was apparently not entirely enthused to see more of his work dramatized by Hollywood. Universal executive Carl Lemlee and James Whale however, promised Wells they would be relatively more faithful in their upcoming project. This resulted in their malevolently entertaining version of The Invisible Man.

The titular role was turned down by both Colin Clive and Boris Karloff; but this fortunately allowed then-unknown stage actor Claude Rains to give perhaps the greatest performance in any Wells adaptation, as we see him slip from desperate chemist to maniacal murderer and, along with the audience, enjoying every insane minute of it.

The film utterly relies on Rains’ performance as Jack Griffin, who sports a macabre sense of humor capped with a wildly infectious maniacal laugh. Given that we can see never see Griffin express or emote, Rains derives all of his dramatic power from a raspy yet commanding baritone voice which, very impressively, effortlessly solidifies him as a thrilling screen presence; losing none of the intimidation or empathy than if the character were visible.

While dropping Grffin’s political diatribes from the novel, the film makes up for it with sheer, evilly good amusement. Whale laces the film with the trademark camp humor he established in The Old Dark House and later took to the nth degree in the beloved The Bride of Frankenstein. Complementing Rains’ unbeatable performance, Whale dazzles us with some impressive visual effects by way of tricky composite shots, wirework and lap dissolves. The illusion of the invisible one’s shenanigans are pretty sound, especially when one considers the film’s age of 84 years.

Rains, effortless in the part, not surprisingly became an instant Universal favourite, later headlining further horrors The Wolf Man and The Phantom of the Opera. But as a versatile character actor, he also made another profound mark in the history of cinema; featuring in unforgettable roles in beloved classics like Casablanca and Lawrence of Arabia.

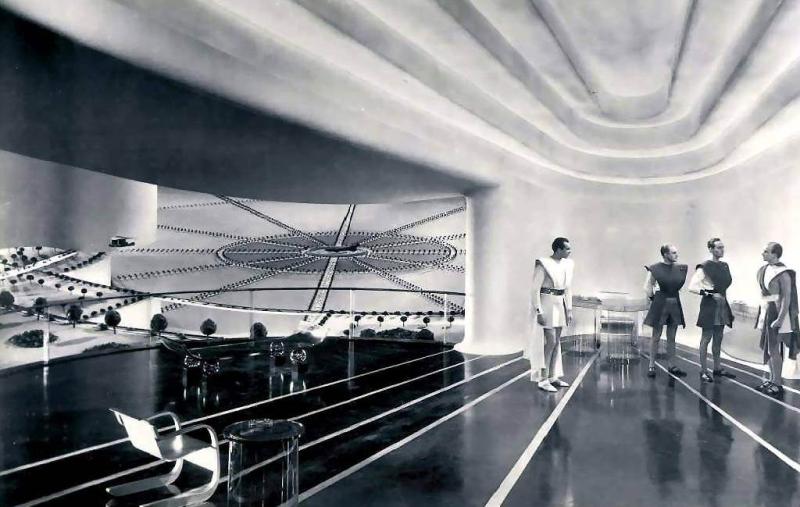

2. Things to Come (1936)

A warning regarding humanities warlike tendencies, yet also prophesizing of a hopeful future, 1933’s The Shape of Things to Come could arguably be considered as Wells’ magnum opus in terms of the author’s political and ideological stance.

This extraordinary and prophetical story may have seemed overly ambitious, perhaps even unfilmable when Wells submitted his treatment for a film adaptation, yet this nonetheless deterred the talented filmmakers behind Things to Come. This wildly impressive production spans the course of an entire century, possessing a powerful premise, relatable subject matter, momentous scope and spectacular effects.

After the carefree citizens of Everytown are mistakenly naive to severe political problems overseas, they are thrust into a devastating, decades-long battle with a hostile, unnamed nation (allusions to Nazi Germany are littered throughout). They must then subsequently confront the horrifying and inevitable consequences of large-scale warfare, before almost totally succumbing to a deadly widespread pestilence, as well as a callous and overly militant leader. It is not until a mysterious stranger visits from afar, that society finally lifts its ignorance, ultimately reforming itself for the better.

When one observes science fiction films made before and since, it is fairly apparent that Things to Come is quite unlike anything in the history of cinema. With a lavish production, enormous scale and universal themes, it seemingly should occupy a revered cultural platform equal to that of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (interestingly, a film that Wells hated). What likely prevents this however, is its emotional distance and ever too fleeting characters.

There is not much time to emotionally invest into what is occurring before we suddenly advance to a future generation via elongated montage. Yet as the picture certainly would have benefitted from a longer running time (its original cut, now lost, was 130-minutes) it nevertheless flawlessly conveys its topics of anti-war and social equality in a way that is fascinating, while still incredibly noteworthy and relevant.

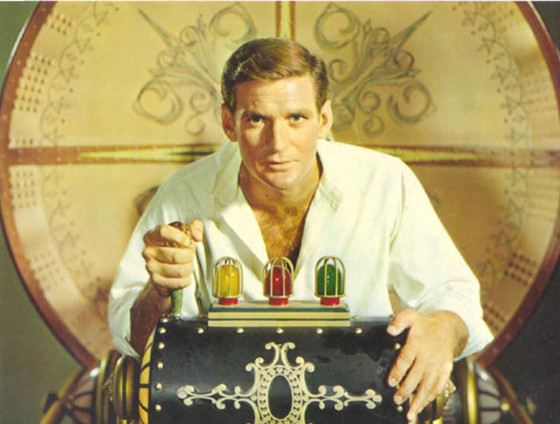

1. The Time Machine (1960)

Charming and compelling, the original cinematic take on Wells’ first success arguably hits home on every account. A generally loyal adaption of the novella, yet entertaining and interesting on its own terms, it possesses an enthralling narrative, charming characters, whimsical tone and an updated theme for the post-war era.

It is the wondrous enthusiasm of Rod Taylor’s George (first initial H, last name Wells) that instantly absorbs us into the film’s adventurous spirit, as he gallops across time witnessing humanity gradually destroy itself through war and environmental neglect, before it splits entirely into the carefree Eloi, and those infamous Morlocks.

Where the 2002 remake mostly failed, this version nicely fills a dramatic void that is felt in the book. Where characters Filby and Weena are relatively dimensionless in the original story; Filby, a faceless acquaintance of the time traveller, and Weena, a childish member of the elflike Eloi; are instead rendered with depth and likeability. The relationship between George and Weena (who is now humanoid and alluring) is elevated to romance, while Filby serves as George’s jovial, loyal best friend and voice of reason.

Differing from the novel also, is the explanation for the evolutionary divide of mankind. Like The War of the Worlds or even Things to Come, there is a similar emphasis on the warlike nature of humanity.

Rather than evolutionary change being caused by the harsh differences between social classes, George learns of a violent, centuries long “war between the east and west”. This answer consequently lacks the ironic satire of the book, but is an equally worthwhile subject, and a wise change in order to contemporize the story.

The Time Machine is a brilliant film, underrated and flawlessly entertaining. While not a carbon copy of the novella, something about it gives off a totally Wells-ian feel that other films on this list lack. With added charm and thrills, it captures a similar wondrous spirit, as well as an enthusiasm for social and technological progress (encapsulated in its main character) that Wells would have likely appreciated, and it’s a tremendous shame that he never lived to see it.

Author Bio: Benjamin Aldis enjoys filming, writing and watching things. He’s a connoisseur of all genres, particularly of Horror and Science Fiction. His presence online – twitter.com/BenAldis.