The 21st Century has been and continues to be an astounding and simply stunning time for cinema. There seems to be no end to the awe-inspiring visuals lighting up living rooms, bijous, drive-ins, and multiplexes the world over.

Taste of Cinema’s tireless and exciting search for the most visually exquisite films of 21st Century has been no easy charge, though several films stood out straight away. The assembled list presented here offers up films of dazzling depth, stirring symmetry, impeccable production design, gorgeous framing, and assured grace. Enjoy!

10. Embrace of the Serpent (2015)

Man’s connection to nature, the tragic loss of a conquered people, and the mean mysticism that’s carried along with it are at the heart-stirring center of Ciro Guerra’s Heart of Darkness-like adventure odyssey, Embrace the Serpent.

The winner of the Art Cinema Award in the Directors’ Fortnight section at the 2015 Cannes Film Festival, this Amazon-set saga of spirituality and enveloping atmosphere is an opulent black-and-white affair that is fittingly plush in 35mm.

This is one of those great and tragic epic jungle films, like Werner Herzog’s Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972) or Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now (1979), and like those films it was also made under extremely difficult conditions made palpable by David Gallego’s immersive cinematography.

The Colombian landscapes are as majestic as they are menacing, making the forests a crazy-quilt of textures and ancient radiance. This isn’t just cinema, it’s a feat of luminous and everlasting strength.

9. The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014)

Gossamer-like, lovely and wistful, Wes Anderson’s The Grand Budapest Hotel thrums with the dual dispositions of the sublime Golden Age director Ernst Lubitsch and the jam-packed chapter and verse of Stefan Zweig.

In this calorie-rich and joyously effete film, exuberance is the mainstay, as it exists in a baroque bubble of an imagined Old Europe where period styles, historical allusions, and joyful generic conventions intersect amidst a seeming compendium of potential films of adventure, emotion, humor, hubris, and tragedy.

The luxury hotel setting, carefully constructed by production designer Adam Stockhausen (exteriors) and Anna Pinnock (she designed the interiors), is the anchor of a shaggy dog story that unfolds over three distinct timelines, where each is shot in three different ratios; 2.35:1, 1.85:1, and the classic 1.33:1.

Among the many eras that Anderson revisits, there are tangible elements of gothic romance and mystery––Hitchcock’s The Lady Vanishes (1938) springs to mind––and with all the trap doors, secret passageways, evil assassins, and sketchy monks, not to mention the inspired inclusion of a secret society of hotel concierges, there’s nods to more Hitchcock (The 39 Steps and Notorious perhaps?) and British Secret Service/spy films à la Carol Reed.

Throw in some stop-motion sequences, a splash of kink, pastiches of American-style comedy of manners, World War I espionage, romantic comedy, broad slapstick, elements of farce, and the feeling of peering into, who knows, Orson Welles toy box maybe? There’s so much stylistic variety––even a black and white melodramatic respite––that the eye and the mind never rest.

8. Hard to Be a God (2013)

The long-gestating final film from Russian cinema heavyweight Alexei Gherman (1985’s My Friend Ivan Lapshin) spent decades in pre-production, was begun in 2000, filmed over a six year period, spent years after that in post-production, and was finally finished posthumously by Gherman’s son, and released theatrically in 2013. Hard To Be a God is that rare reward of visceral cinema, and an epic in every sense of the word.

Adapted from the underground sci-fi cult novel by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky––the sibling duo who penned Tarkovsky’s Stalker––Gherman’s crowning achievement takes place on an alien planet Arkanar, eerily like our own only here the Renaissance never happened, resulting in a never-ending Middle Ages nightmare.

Shortly after I’d seen a wondrous 35mm print of Hard to Be a God at the Cinematheque in Vancouver, Canada, I had the good fortune to visit the Getty Museum in Los Angeles during an exhibit of Hieronymus Bosch’s work.

The medieval master’s unexpected imagery, dripping with macabre detail of hellish landscapes, fantastical and freakish figures, and startling religious narratives with cruel men and demonic beasts often adorned with halos or the twisted maws of damnation; here did I see with bracing clarity what Gherman and his gifted dual cinematographers Vladimir Ilyin and Yuri Klimenko were going for with Hard to Be a God.

Their richly detailed black-and-white cinematography recreates Bosch-like tableau and Brueghelian details of barbarity, beauty and grotesque human contest. If a more immersive, ingrained and extravagant film than this exists, I’ve yet to see it.

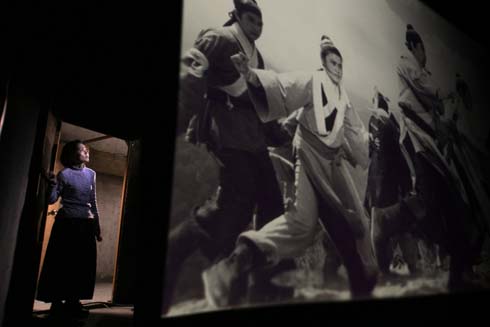

7. Goodbye, Dragon Inn (2003)

From one of the major players in New Taiwanese Cinema (next to Hou Hsiao-hsien and Edward Yang), Tsai Ming-liang details urban alienation with the deft eye of a master. Goodbye, Dragon Inn, set inside a doomed movie temple on the eve of its closure, demonstrates Tsai’s signature slow cinema approach of long fixed shots and abrupt eruptions of surreal humor––often courtesy of the expressive and paradoxically impassive actor and muse, Lee Kang-sheng.

In this film the Fu-Ho movie palace is populated by forlorn souls, both living and dead, wandering and wondering within the faded, once embellishing interior, ravenous for connection. Outside the Fu-Ho a torrential downpour drenches the streets of Taipei, establishing and underscoring a tangible yet allusive sense of ghostly melancholy that torments and troubles the picture in what is widely and rightly regarded as Tsai’s masterpiece.

6. The Master (2012)

A polarizing but prominent director (as so many on this list are), Paul Thomas Anderson is, as Rolling Stone’s Peter Travers suggests, “…a rock star, the artist who knows no limits.” Travers goes on to say rather astutely that “ [The Master is] written, directed, acted, shot, edited and scored with a bracing vibrancy that restores your faith in film as an art form, The Master is nirvana for movie lovers. Anderson mixes sounds and images into a dark, dazzling music that is all his own.”

Anderson’s The Master presents a powerful and precise portrait of a troubled, violent, and often soused drifter named Freddie Quell (Joaquin Phoenix), suffering from shellshock after WWII he eventually, in 1950, runs into the charismatic cult leader Lancaster Dodd (Philip Seymour Hoffman). Mentoring Freddie, Dodd brings him into his religious movement, the Cause––a simulacrum for Scientology, and Dodd of L. Ron Hubbard.

A compelling, challenging, maddening and invigorating film, cinematographer Mihai Mălaimare Jr. (who won many awards for his fine work here), presents a fluid and unbroken chain of high contrasting imagery. This is one haunting and lamentable honey of a picture.