5. Cries and Whispers (Ingmar Bergman, 1972)

Bergman became famous off the back of his black-and-white dramas. His style is a combination of stark lighting, extreme close-ups and gloomy existential monologues. For Cries and Whispers however, he showed the world just how good he could be at utilising colour for dramatic effect.

This is a film that couldn’t be in black-and-white. As Bergman himself said: “All of my films can be thought of in terms of black and white, except Cries and Whispers.” Bergman, in collaboration with longtime cinematographer Sven Nyqvist, uses three main colours in strong contrast with one another: Red, white and black.

Red here is said to represent the inside of the soul — painted on the manor’s walls so dramatically that they speak higher than any of the characters. Draped in strong blacks and whites, the four women war with each other in a deeply harrowing way. These dramatic conflict is made even stronger by the use of natural sunlight to shoot the movie.

The absence of any lighting trickery gives the film a high emotional immediacy. Although due to its deep expressionist style, Cries and Whispers could hardly be called a “realist” movie, Bergman finds a way to utilise light to make its themes scream out at you. Far and away his best looking movie.

4. Blade Runner (Ridley Scott, 1982)

Is there any actor better suited to complex, adult dramas than Harrison Ford? From Frantic to Presumed Innocent to Witness, his characters feel real and lived-in, as if they will keep going long after the film ends. His best role however is in Blade Runner, whereby he plays a hunter of replicants in a rain-soaked, ultra cool, multicultural Los Angeles.

The movie is a great one not just for its elegant screenplay, evocative score and great performances, but simply for the way it looks. Blade Runner not only looked like nothing before it, but became the inspiration for many cities-of-the-future movies, from The Matrix to Dark City to even The Fifth Element.

The lighting plays a massive part in the film’s success. Aping the techniques of film noir, where the complex contrast between light and shadow seeks to show the moral complications of the main characters, we see light filtering through shuttered windows, drizzled through rain and reflected off huge, imposing advertisement billboards.

Although somewhat a film of its day, it has a timeless quality that still beguiles during the present moment. Also worth watching is its sequel, lensed by the brilliant Roger Deakins, which is still playing in cinemas at this moment!

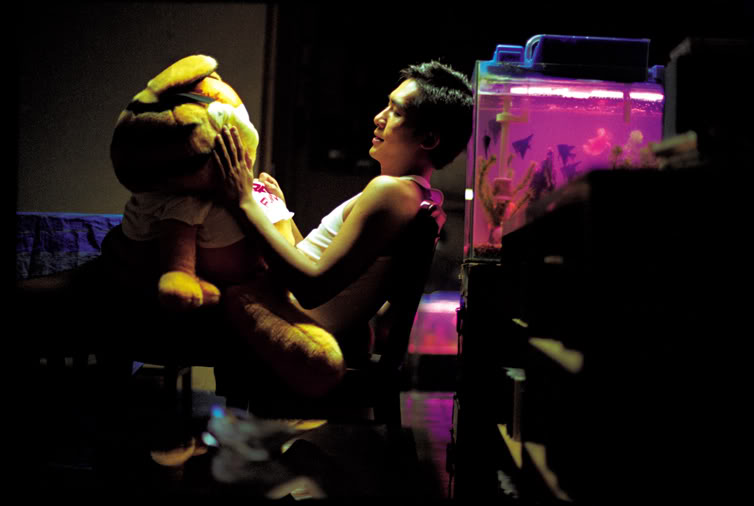

3. Chungking Express (Wong Kar-Wai, 1994)

When Wong Kar-Wai’s first film, As Tears Go By, landed on the scene in 1988, it established him as one of the most forward-thinking directors around. He further solidified his position as one of Hong Kong’s greatest auteurs with Chungking Express, a great example of how lighting and narrative can be used together to create a haunting romantic effect.

Set in a Hong Kong awash in neon lights and feeling completely in the future, Kar-Wai tells the story of two lovesick policeman who like to hang around the famous Chungking Mansions.

It is not a conventionally told story, but this is to its strength. Instead it is flash of fast-moving images, American pop music and non-linear storytelling. A film about love, both gained and lost, the style really helps to demonstrate the wooziness of romance in a city as crazy as Hong Kong (although it also helps when you have the irrepressibly handsome Tony Leung starring in your film).

The colours splash about the screen in a truly expressionist sense. They are used in a very strong way in order to grab the viewer’s attention and never let go. In the hands of a lesser director, this could seem like empty style. With Wong Kar-Wai, it helps to establish Chungking Express as one of the 90’s best films.

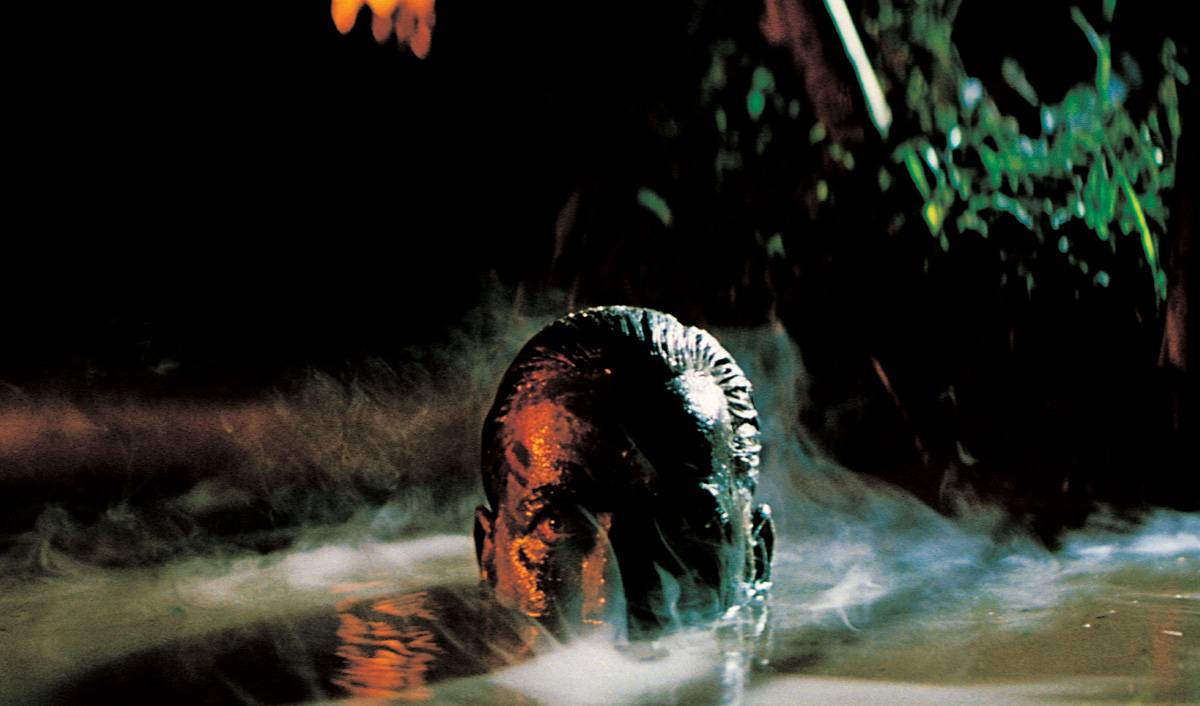

2. Apocalypse Now (Francis Ford Coppola, 1979)

Apocalypse Now changed the face of the war movie. While many films had made it look either like hell or a place for patriots to prove their mettle, nobody had hitherto turned it into all of that and more.

The film is a true odyssey that takes in the darkness, the humour, the cynicism and opportunism of the Vietnam war like no other. This effect is largely achieved by the sophistication and complexity of its lighting scheme, again utilised perfectly by Vittorio Storaro.

So much happens in Apocalypse Now that it transcends the war genre to such an extent that it becomes its own beast, hardly matched before or since. Storaro helps to achieve this unique vibe by approaching every sequence with its own individual colour scheme: from the blazing oranges of the helicopter attack to the arresting blues during the search in the forest for mangos.

Telling a story of venturing into the unknown, the lighting of the film always overwhelms the characters; both in its beauty and its epic-ness.Once we finally meet Kurtz, his face is almost always framed in darkness. Much like in the opening scene of The Godfather, which was inspired in part by The Conformist, surrounding Brando’s face in such a way lends an extraordinary power to his speech.

1. The Conformist (Bernardo Bertolucci, 1970)

Easily a contender for one of the most beautiful films ever made, the images conjured up by legendary cinematographer Vittorio Storaro are so potent that the viewer can almost get drunk on them.

While many films are described as breathtaking, there is something so audacious in The Conformist’s images that it feels unique in cinema history. Starring a protagonist who doubts his very own thoughts and feelings as he tries to fit into the fascist Italy of 1938, the complexity of the lighting is used to complicate his ideals and show that nothing is ever actually like it seems.

The colour scheme is equally loaded with psychological implications, highlighting the many different sides of Marcello’s (Jean-Louis Trintignant) sexually repressed personality. As a result it remains one of the highest achievements of the film medium and a capitulation of all that was brilliant about Italian cinema in the 50s and 60s.

From the opulence of Visconti to the orgiastic free-wheeling of Fellini to the radical modernist daring of Antonioni, Bertolucci finds a way to synthesis all of these traits into a one-of-a-kind experience. From the infamous murder in the woods to the dance scene in a Parisian café, the film never lets up from looking absolutely gorgeous. As a result, The Conformist is filmmaking at its most fearless.

Author Bio: Redmond Bacon is a professional film writer and amateur musician from London. Currently based in Berlin (Brexit), most of his waking hours are spent around either watching, discussing, or thinking about movies. Sometimes he reads a book.