Sadness is anything but desirable, yet people will seek specific movies to harvest this emotion. It’s a phenomenon that could be attributed to the stagnated emotions of first world citizens, whose comfortable but mundane lives are deficient in the emotions that give a poignant meaning to existence. Or it’s a normal pursuit that unites all classes of people in the artificial evocation of feelings; the pure, primal emotion unconnected to personal suffering.

It’s a fictional character’s sadness and you’re only a spectator. Movies can be a safe space for crying without baggage. Or maybe it’s that sadness is actually not so bad, and its presence only serves to strengthen happiness.

Whatever the reason, this sadness addiction has fostered a market for melodrama that is Hollywood’s unsaid golden ticket. Thankfully, pop-sadness is inferior to the sadness that comes naturally through storytelling. The sadness must serve the story, and not the reverse.

The following films are all great films, but also sad films—some of the saddest ever created. However, this does not mean they are manipulative tearjerkers that will have you sobbing from contrived plot points. Though you may certainly experience the same crushing effect as the former will dictate, these movies are more inclusively sad. The sadness is the conceptual makeup of the film, not just the reaction to the film. It’s not contingent on your tears.

Warning: Spoilers

10. Dancer in the Dark

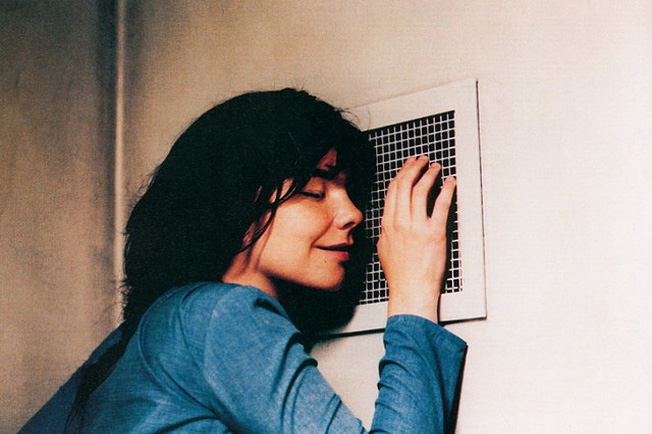

Lars von Trier’s industrial metamusical Dancer in the Dark has Bjork playing the lead role, and her bare bones acting makes her character one of the most sympathetic in modern cinema.

Bjork plays Selma, a Czech factory worker living in America with fantasies of American ostentation. These come in the form of musical numbers, remembered from various films, and invoked to enrich dull and painful experiences. She also visits the theater regularly and takes a drama class. Selma’s real life, separated from the fantasy to which she escapes, is devoted to her young son, Gene. Her secret is that she is going blind, and that her son has inherited this condition.

Selma’s true goal is to save enough money to pay for Gene’s operation before she is too blind to work. However, a trusted but troubled neighbour and policeman, Bill, discovers her stash and steals the money to pay off his debts. Now blind, Selma confronts him, but Bill reverses roles and accuses her of stealing from him. He apprehends her at gunpoint, then tells his wife to call the police. After she leaves, he forces the gun into Selma’s hands and pleads for her to kill him. She does so, out of mercy.

Selma is arrested and put on trial. Principled to a fault, she is unwilling to reveal the truth of the events to protect the legacies of Bill and her son. So Selma is found guilty of murder in the first degree and is sentenced to death. Though she can pay for an appeal with the operation money, she refuses, and accepts death so Gene can see.

On the fateful day, she panics whence the hood is applied and stalls the execution, but her friend intervenes and places Gene’s glasses in her hands, indicating that the operation was successful. This calms Selma completely, and, singing a musical number, she is dropped through the floor and her neck is snapped.

Though accused by some as insultingly melodramatic, Dancer in the Dark has enough humanism and stylistic nuance to give cinematic sadness a radically new composition.

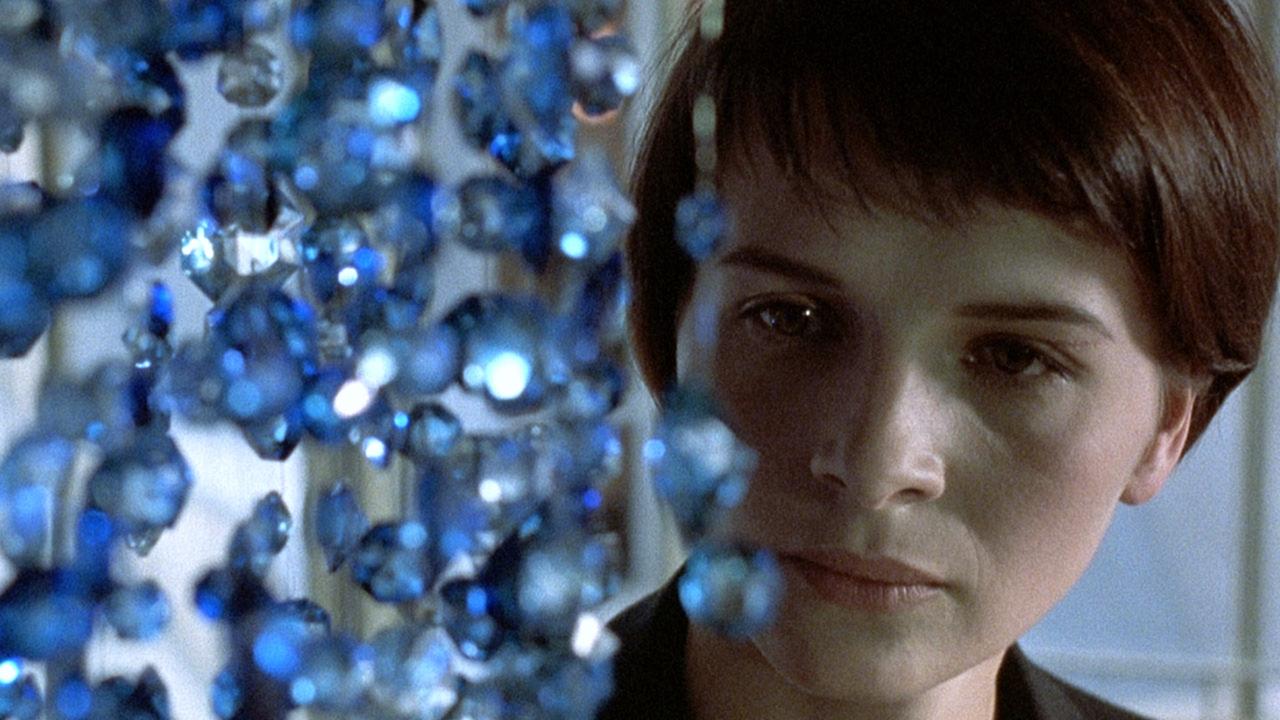

9. Three Colours: Blue

Much has been said about this French arthouse classic for its aesthetics and symbolism, but the root of the film is a deep sadness which buoys the stylistic beauty.

Three Colours: Blue follows Julie, a woman who has lost her husband and daughter in a car accident. Severely injured herself, she attempts suicide at the hospital upon hearing the horrible news. She is unable to swallow the , however, so she comes to terms with the deaths—so we think—and is eventually discharged.

As a safety mechanism for this unbearable emotional pain, Julie becomes apathetic and abandons the abundant life she previously occupied. She sells her mansion, discards her possessions and those of her husband and daughter, and moves to a small apartment where she lives alone and does nothing. Julie understands that attachment is suffering, so she forsakes a life that could end up hurting her the way the accident did. She chooses the safety of emptiness over the agony of love. She’s so detached she cannot even cry.

Despite her withdrawal, people try to reach her, and some people she happens upon by accident. One thing is clear, though: people love Julie, and are attracted to the warmth she is trying to suppress. She fights the intrusions upon her ascetic life but can only hold out for so long. She relents, and lets herself be emotionally connected once again.

The ending shows Julie crying for the first time since the accident, finally realizing that agonizing love is better than no love at all.

8. Million Dollar Baby

Few movies are as unrelentingly depressing as Million Dollar Baby. The film has only two modes: quietly morose, or mercilessly devastating. Even the lighting is greyed for maximum gloominess.

This Clint Eastwood-directed drama tells the story of an underdog female boxer Maggie (played by Hillary Swank) who seeks the tutelage of Frankie, a well-respected but past-his-prime trainer (played by Eastwood himself). Maggie wants success, not for herself but for the betterment of her family back in Missouri; and Frankie wants redemption, both as a trainer and as a person, the guilt of which has ruined his life. After much hesitation, Frankie takes Maggie on, and teacher and student form a bond that is so painfully sweet, setting up a third act that sends the buildup crashing down.

Under Frankie’s teaching, Maggie fights her way up the lower rungs of boxing to compete for the welterweight title and the chance at a million dollars. However, during a break in the title fight she is suckerpunched. The punch sends her falling, off balance, into a stool. It breaks her neck and paralyzes her body.

The remainder of the film sees Maggie bedridden in ICU and unable to live a quality life, while Frankie punishes himself in connection with her injury and the absence of cosmic justice. To make matters worse, Maggie’s family visits, whom the boxing winnings were going towards, and their lack of care towards Maggie, who is revealed to be the only good person in the family, is more horrifying than even the ensuing events.

All the family cares about is the transferal of assets when Maggie dies. Her family’s coldness, combined with the increasingly degenerative condition which causes the amputation of her leg, makes Maggie desperate for an end.

After Maggie tries and fails to kill herself, Frankie, initially reluctant but finding that this the only possible redemption, does it for her. He plunges adrenaline into her body and Maggie dies.

7. La Strada

Love makes good people do bad things and bad people do good things. La Strada explores this phenomenon as completely as an hour and a half ever could.

A young woman, Gelsomina, is sold to a traveling entertainer by her impoverished family. Zampano’s the entertainer. He’s a bully of a man, angry at the world, and treats Gelsomina as a slave. Gelsomina, conversely, possesses an immovable joy; and, despite the treatment, she remains a loyal and enthusiastic assistant. This makes Gelsomina’s fate so much more depressing.

During their travels, Gelsomina meets another entertainer nicknamed The Fool, with whom Zampano has a negative history. The Fool befriends Gelsomina, and rebukes her reluctance to leave circumstances which hurt her. He tells her that everything is useful, even her, and even the pebble he displays in his hand; but if the pebble is useless, everything, even the stars, would be useless too. Before leaving for good, The Fool tries to convince Gelsomina to leave Zampano. She can’t. She loves him, so she rejoins the strongman and they resume their traveling.

On the way to the next town, they come across The Fool again, this time broken down on the road. Wanting redemption for his previous ill-treatment, Zampano beats him severely, accidentally killing him. This event breaks Gelsomina, who falls into a malaise that renders her unresponsive.

Zampano tries to help her, but she is too depressed to be of any value. He deserts Gelsomina while she’s sleeping, but not before covering her body with a blanket.

Years later, Zampano is wandering another town when he hears a song Gelsomina used to play. He locates the source, a woman who tells him that the song’s originator was found on the beach near the town. The woman’s father took Gelsomina in but she was too far gone to be saved. Disturbed by this news, Zampano travels to the same beach and falls to his knees.

Zampano, echoing The Fool’s monologue from earlier in the film, looks to the stars and breaks down and cries. Whether he sees that Gelsomina died for no reason, or that she died for a very clear reason, and that reason is him, he can only despair either way.

6. Blue Valentine

Blue Valentine is a middle finger to the sappy, everything-works-out-in-the-end love stories. It’s a brutally honest portrayal of love and the people who fail it.

The film tracks the relationship between Dean and Cindy, played by Ryan Gosling and Michelle Williams, respectively. It begins nicely enough: they meet through Cindy’s grandmother when Dean delivers furniture to the retirement home. The dating goes well, but soon after Cindy gets pregnant, but she’s unsure if Dean’s the father. She decides to have an abortion, but declines at the last minute. Dean agrees to father the child regardless of paternity.

Five years later, Dean and Cindy are living together and raising the young child. They are frustrated with each other, but remain amicable for the benefit of their daughter Frankie. Hoping that a romantic evening will improve their relationship, they rent a motel for a night, but the sudden appearance of Frankie’s possible father causes a rift reignited from the past. The couple fights throughout the evening until Cindy leaves the next morning for work.

Dean shows up drunk to her work and fights with her and the doctor, who’s been trying to seduce Cindy. After the altercation, Cindy tells Dean she wants a divorce, and they speak about the consequences this decision will have on their daughter.

In a heartbreaking ending and the saddest moment in the film, Dean complies with Cindy’s wishes and walks away from the house. Frankie runs after him and pleads with him not to go. He sends her back home, and she cries in her mother’s arms as her dad leaves the family.

Blue Valentine has someone most people can relate with, whether it’s the father, mother, or child, as every complication of the familial bond is explored and executed in a supremely affecting way.