8. Charles Foster Kane, Citizen Kane

In an odd reversal of the introductions of characters summarizing their traits and personality, the introducing scene that shows Charles Foster Kane in Citizen Kane only works to set up the central mystery that the rest of the film would spend uncovering: the meaning of his dying word, “Rosebud.”

With a somber montage that depicts the Kane mansion, hidden behind tall, foreboding gates and on top of a hill like a castle on a dreary night, the audience first glimpses Kane through a quick montage of oddly composed shots, where a snow globe he’s clutching falls from his hands and shatters on the floor. With a close-up of his mouth as snow is superimposed over it, he whispers “Rosebud” and then dies.

The next scene is a newsreel summarizing Kane’s entire life–his birth, ascension as one of the leading newspaper figures in the world, a disastrous political career, a scandalous marriage, and a long, slow decline that ended in death. But as the reporters that comment upon the newsreel note, this doesn’t tell them anything about who the man was–just what he was. And starting from this mystery and point of obfuscation, the rest of the film attempts to uncover who Charles Foster Kane was as a person.

7. Alex DeLarge, Clockwork Orange

After an ominous synthesizer arrangement drones over a red and white title card, the scene cuts to the glaring face of a young man wearing a black bowler hat and with lashes flaring out of his right eye. His blue eyes have a glint to them as a steady, deliberate voice-over narration (from this same young man) begins, introducing the audience to the figures and scene that’s slowly revealed as the camera pans out. He takes a sip of what looks like milk and is flanked by three similarly bizarrely dressed young men.

His feet are kicked up onto the belly of two naked female mannequins who are in crab positions with their legs intertwined and wearing brightly colored wigs. Above them, the words “Moloko Vellocet” are written in a white psychedelic font against an all-black wall. We see that this is an entire bar that is outfitted with lewd naked female mannequins, all wearing bright wigs, with other people also there and drinking the strange white drink.

“There was me, that is Alex, and my three droogs–that is Pete, Georgie, and Dim,” says the narration over this scene, “And we sat in the Korova Milk Bar trying to make up our rassoodocks what to do with the evening. The Korova Milk Bar sold milk plus – milk plus vellocet or synthemesc or drencrom, which is what we were drinking. This would sharpen you up and make you ready for a bit of the old Ultra-Violence.” The words he speaks are strange, a mangled slang of English and Russian, and the description of the bar and what it serves is nothing that exists in our present time.

But perhaps the most disturbing–and telling–part of his narration, which fits in with the menacing scowl on Alex’s face, is his mention of engaging in “a bit of the old Ultra-Violence.” What follows is said Ultra-Violence, as the audience watches just what horrifying acts Alex has in his rassoodoock for him and his droogs that night. But right from the start, it’s easy to see that there is something awfully wrong with this character–and the world he lives in.

6. The Joker, The Dark Knight

A man with his back to the camera waits on the corner of a street holding a clown mask. A car pulls up and he puts his mask on before entering. Meanwhile, two men wearing clown masks zipline across the roof of a building. The group in the car enter a bank firing guns and announcing that this is a robbery. On the roof, one of the men disables the alarm and is immediately shot by the other man.

Inside, the men in clown masks pull off the heist, although one is shot by the bank manager. With two of the robbers hiding from the shotgun-wielding manager, one asks the other if the manager is out of shots. The clown nods and the other one pops up and is shot.

Once the robber breaking into the vault opens the door, one of the robbers shoot him. That robber comes out with bags of cash and pulls a gun on the remaining robber, guessing that he’s the one that was ordered to kill him. The robber replies that no, he’s supposed to kill the bus driver and stands back. A bus backs into the bank and runs over that robber.

The bus driver comes out and helps the remaining robber load in the bags of cash, and then that robber shoots the bus driver. Now the only one left alive on this heist, the bank manager taunts him, asking him what he believes in. The robber comes up, sticks a smoke bomb in his mouth, and pulling off his mask replies, “Whatever doesn’t kill you makes you–stranger,” revealing the grotesque clown makeup he has on underneath and his Glasgow smile.

The Joker gets in the bus and disappears into a crowded street filled with similar school buses just as the police arrive. It’s a ferocious introduction–and the opening scene to The Dark Knight–to one of the franchise’s most memorable and dangerous villains.

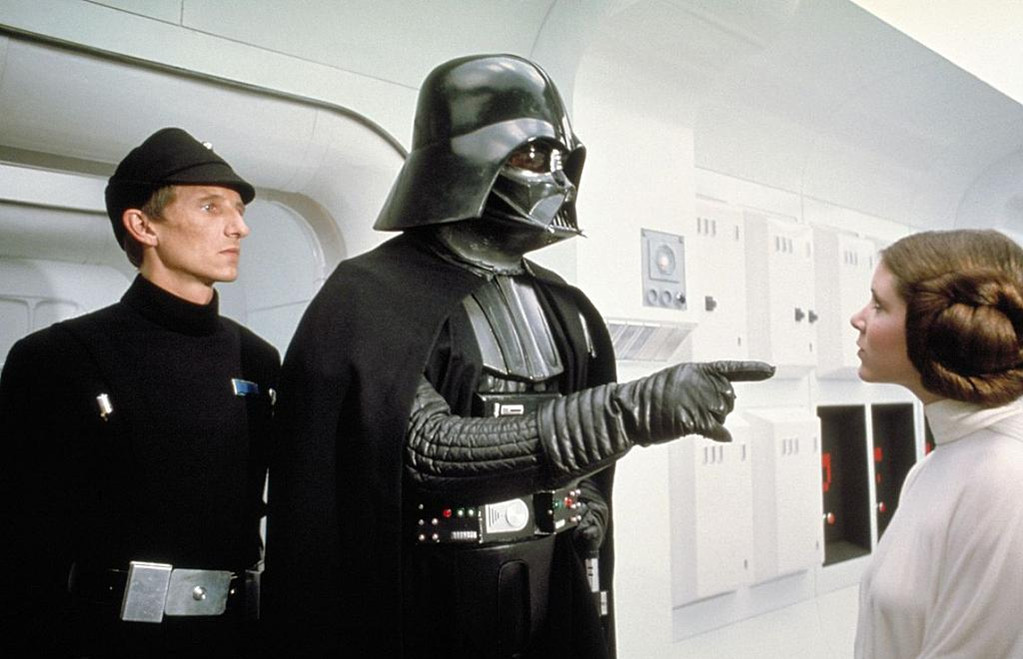

5. Darth Vader, Star Wars

Contrast is an important concept in the visual arts. On a semiotic level, the concepts of “light” and “dark,” or “black” and “white” permeate deeply throughout nearly every culture to be associated with “good” or “bad” and “innocent” and “corrupt.” George Lucas understood these ideas–and other semiotic concepts–well, as Star Wars so clearly demonstrates.

At the point in the film where Darth Vader shows up, we’ve been following our ragtag group of good guys: Luke, the naive newcomer; Obi Wan Kenobi, the veteran and his teacher; R2-D2 and C3P0, comic relief and distinctly different robots from the others we encounter; Han Solo, the rouge; and Princess Leia, the royal leader of the Rebels. Each one is distinct from each other, unique in presentation, and different in characterization.

Contrast this with the Empire’s forces: all faceless, nameless soldiers wearing identical uniforms of white with black outlines. Although we hear them speak, it’s mostly in simple military phrasing. And since they’re fighting our protagonists, they’re obviously the bad guys. In the midst of all of these uniform figures, and with ominous music playing on the soundtrack, walks in an 8-foot tall figure that’s dressed in all-black from head-to-toe, looking around at all the dead rebel soldiers on the ground.

We can hear him breathing, as if pneumatically, and he speaks, but it’s in a deep, computerized voice–and the first time we hear him he’s strangling a rebel soldier and threatening him. It doesn’t take a PhD to understand that this is the main bad guy of the movie, but his presence and character design is so iconic that it’s become one of the most immediately recognizable images in Western civilization.

4. James Bond, Dr. No

The camera pans across the swanky casino floor of Le Cercle, where well-dressed people gamble away at their game of chance. A beautiful woman plays Baccarat, and the camera zooms out to the profile of a man playing against her from across the table. The man wins the first hand, and then–after the woman secures a loan from the house–he wins another.

While the woman writes a check to keep playing, the camera focuses on the man’s hands as he opens up a cigarette case and takes one out. She says to the man, “I admire your luck, Mister…?” The camera cuts to reveal the man, who’s lighting a cigarette, to which he replies: “Bond. James Bond.”

Puffing away on a cigarette, she asks if they can raise the limits, to which he acquiesces as the “Bond Theme” plays on the soundtrack. As they are dealt another hand, Bond stares seductively at the woman across the table, lightly flirting, “Looks like you’re out to get me.” He wins the hand but is interrupted by a messenger. Bond takes his winnings and excuses himself from the table.

Before he leaves, however, the woman comes up to him and she and Bond make a date for the next day. He hands her his card while being handed a stack of cash that’s his winnings and then smoothly walks out of the casino–while she watches him the whole way.

One of the most iconic introductions in cinema, Sean Connery’s James Bond defined the character for decades to come, and his introduction in the first film is pitch-perfect. Showing Bond to be handsome, charming, sophisticated, good at cards and seemingly irresistible to women, this intro works as shorthand for what a cool, well-dressed, confident man was considered at one point in time in the 20th century.

3. Vito Corleone, The Godfather

While the screen is still black, the audience hears a man utter the line, “I believe in America.” The scene fades in and the camera slowly zooms out from the man who spoke those opening lines, which has led to a story about his daughter having been brutalized by a group of men. He tells this story, to an unseen figure in hopes of finding getting justice for his daughter–the kind of justice that’s not handed down by a court or a judge. The man seated across from him listens patiently, and the next cut is to this figure’s reaction–he’s an older, heavyset man in a tuxedo, and this is the titular Godfather.

Replying to this man in a deliberate tone that reveals the naturalistic performance Marlon Brando brought to this part, The Godfather strokes a cat on his lap and begins to ask this man why he should bring harm to men that he does not know. As the audience takes in this scene, they begin to realize that The Godfather is an incredibly powerful man that could easily take a life with a word–and here he is, on the day of his daughter’s wedding, meeting with various guests who have favors to ask of him. Favors they cannot ask of anyone else.

Moody, atmospheric, and perfectly shot and framed, the introduction of The Godfather sets the tone of both the character and the movie–as a man of honor and tradition but also one whose business is of crime and murder. Setting the gravitas the film holds throughout, Vito Corleone–The Godfather–is presented as the heart and soul of the Corleone family, and one that would guide their story even unseen in future films.

2. Gunnery Sergeant Hartman, Full Metal Jacket

The first half of Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket is a crash course in the boot camp program for the United States Marines. Methodically edited and paced, it moves at a montage-like clip from the perils and difficulties a group of new recruits face as they are trained for combat in Vietnam.

After the opening credits–which show the characters getting their heads shaved–the opening scene introduces both the characters and the audience to Gunnery Sergeant Hartman, a tough-as-nails training sergeant that immediately sets the tone of how the military aims to strip away individuality and self-worth to create lean, mean fighting machines.

As Gunnery Sergeant Hartman (played to perfection by real-like former drill sergeant R. Lee Ermey) states, “I am hard, you will not like me. But the more you hate me, the more you will learn.” He then unleashes a torrent of verbal abuse towards the recruits, including physically assaulting them.

With Kubrick’s sweeping cinematography following Hartman’s incredibly disciplined and precise insults meant to degrade the privates’ self-regard and worth, watching Hartman’s introduction–which also serves as the introduction to the movie itself–gives audiences an unflinching introduction to life in the US Army.

1. Colonel Hans Landa, Inglourious Basterds

Like a charming wolf, Colonel Hans Landa of the SS approaches the cottage of a dairy farmer in the French countryside. After admiring the farmer’s beautiful daughters, he asks if he and the farmer can speak alone. The two men take a seat at a table and conduct a brief interview in French about how some of the farmer’s neighbors, who were Jews, are unaccounted for. Landa is unerringly polite throughout the conversation, calling it a mere formality.

He asks if the farmer can speak English, and as he can, they switch the language of the conversation. Once speaking this foreign language, Landa discusses how he enjoys the nickname he’s garnered, “The Jew Hunter,” and that he understands how they think.

Landa also reveals that he knows the farmer is hiding his Jewish neighbors in the house and offers him a deal: if he points out on the floor where they are hiding, he and his family will not be bothered for the remainder of the war. Landa also suspects that because he had not heard anything from below, the farmer’s Jewish neighbors must not speak English.

Scared but understanding what Landa is offering him, the farmer points out to him the positions beneath the floorboards his neighbors are hiding. Landa calls in his SS soldiers while concluding the conversation with the farmer, making it sound as if he is leaving, while pointing out to the soldiers where to aim their guns. Lands stops speaking and the soldiers open fire. Everyone under the floorboards is shot and killed, saved one: a teenager named Shoshanna. Landa takes out his pistol and begins firing at her, but she makes it far enough to escape. He shouts, “Farewell, Shohanna!” and has a bit of a smirk on his face.

Many characters on this list also introduce their movie as a whole, and Colonel Hans Landa (Christoph Waltz) similarly opens Inglorious Basterds. Hypnotic and charming in his delivery, Landa is a dangerous character precisely because he is so clear-eyed. This isn’t a raving maniac but a man that you may enjoy having a drink with if you didn’t know his occupation. A master of dialogue and characterization, Quentin Tarantino made a memorable character with Hans Landa, with an equally striking introduction to remember him by.

Author Bio: Mike Gray is a writer whose work has appeared on numerous websites and maintains a TV and film site at MeLikeMovies.com.