8. Toute une nuit by Chantal Akerman

One of Akerman’s greatest films, translated as The Whole Night in English, is an example of pure cinema minimalism. One of the easiest film plots to describe, it is essentially a movie of encounters in the night, most fueled by love or lack of love.

What is exactly so unique about the film is its use of the frame as a place in which people wait, then embrace or turn away, their lovers, moving away and out of the known “box” which they are trapped in then, escape.

Cinematically the film is a work of harsh simplification in that it proves, like other of Akerman’s films, that anyone on-screen is within a frame, a box. The movement from on-screen to off-screen is Akerman’s form and its bold simplicity is exactly what disconnects it from every other film made.

Can be found on YouTube.

9. Mix-Up ou Meli-melo by Francoise Romand

Endorsed by the great critic Jonathan Rosenbaum, an uncanny documentary that stylistically proves its all too complex narrative. The film is about babies that are switched at birth and the mothers and families that dispute whether or not they have been given a daughter that is not theirs, but of another family.

It’s a striking achievement of cinema (that can be found on YouTube) that utilizes each family as a group that looks through surfaces, through windows and glass, to understand the truths of their lives. Many sections of the film literally involve members of each of these families as they move from one side of a window to another, reinforcing the film as one about cutting through the glass that provides a barrier between the known truth.

10. Tetsuo, the Iron Man by Shin’ya Tsukamoto

A tough watch in the sheer cringe which accompanies its content, nightmarish and strange, Tsukamoto’s film is a portrait of fetishistic behavior that reflects a societal necessity, obsession.

Only a bit over an hour the film can be described as about a man that convulses into a painfully metallic man, sexually and violently arriving at transformations that push him physically further and further into a devolved mess. The sound design matches, and signals, changes that visually occur with the man as well as the “narrative” transformation the film takes, very specifically operating in an “unreal” sphere of comprehension.

Not for those that want to be comfortably brought from one stage of a narrative into another, or those that want to enjoy classical filmmaking in any sense, but essential as a viewing nonetheless. Tetsuo truly is a vision unlike any other in its devolving, sporadic sense of narrative composition.

11. Blue by Derek Jarman

What to some is a remarkable last “film” from the bold Derek Jarman is to others something entirely different, artistically astounding nonetheless. Featuring only a blue screen, Jarman’s work is a feat of incredibly detailed, immersive sound design that proves the world of its narrator, Jarman himself, as he loses his eyesight and dies of AIDS.

That is to mention the screen itself does seem to change a little, shifting subtly in shade over the course of the 79 minute running time, forcing a viewer to grapple with the reality of the film’s visual approach. What it represents is all too clearly beyond the simple explanation “to symbolize the loss of eyesight” and more revolves around the viewer in relation to the screen and the transformations that occur within the soundscape. Does one only “see” a blue screen when they watch Blue?

12. Melancholia by Lav Diaz

As is consistent with Lav Diaz and his work, Melancholia is “long” and takes 7 hours 30 minutes to complete. Unlike any films in the known realm of “conventional” cinema, Diaz’ film utilizes a wide canvas to play and manipulate with the narrative expectations of his audience.

The film begins as a story of a pimp attempting to recruit a prostitute in a small village. A nun also walks around the town daily, asking for money for the poor. Ironically, the people rarely give to her as a result of their own poverty. From this simple beginning, the film expands outward in unprecedented narrative occurrences that, as mentioned above, defy and manipulate the simple expectations that come with the opening of the film in contrast to where and when the film, inevitably, ends.

13. Synecdoche, New York by Charlie Kaufman

The pinnacle of Charlie Kaufman’s work, finally directing his own script, is this absurdly complex and emotionally draining opus. About a theater director, played by Phillip Seymour Hoffman in quite possibly his best performance, named Caden Cotard that begins to discover his life is crumbling around him. His wife, played by Katherine Keener, Adele explodes into greater success than Caden ever has had himself and takes their daughter with her to Germany, showing off her miniature painted portraits in galleries.

Caden though gets a surprise grant to put on a great work, opting to stage his life, and the world around him, in the form of a play. This staged life grows bigger and bigger and the production begins to have characters playing other characters, as they play other characters. New York City itself is replicated in Caden’s production, never ending in its expansion to encapsulate the entire world as Cotard knows it and wants others to know it.

Intensely paradoxical and dense, full of humor and classic Kaufman jokes concerning mortality and shame, regret, this work is uncategorizable.

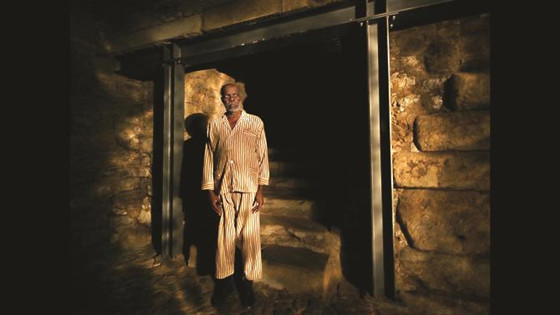

14. Horse Money by Pedro Costa

Without a doubt the best and most radical film of Pedro Costa’s, a confounding masterpiece starring the familiar Ventura. As always, Costa’s “characters” are playing themselves yet are consistently staged to physically impress the stagnancy that possesses their lives, lit to prove how little light is given to them in their existences.

Ventura here is especially breaking down, endlessly walking through corridors of a hospital, hospitals, hearing and seeing those he thought died long ago. His mind is unraveling so time itself is becoming more uncertain: where and when is he?

No films possess the entrancing emptiness of this particular work. It’s a film of impeccable symbolism that transforms all that is on-screen, and off, into pieces of an unsolvable, sauntering, floating jigsaw puzzle which may, or may not, have all the pieces necessary for completion, for understanding.

15. Kaili Blues by Gan Bi

Perhaps the only film similar to Horse Money in its slippery conception of how time, of objects and characters that gain different names and are found in different places, cannot be pinned down and consumed.

Radically different from Costa’s style though, Gan Bi’s film visual approach considers the fog of the filmmaker’s town, the trains that pass by, in informing what is pursued. In other words, the visual style is difficult to pin down, difficult to retain its rhythm in its pursuit of disorienting audiences. It can be noted, but not revealed, a major stylistic shift in the language of the film occurs quite abruptly into the film’s running time, proving to be a gashing symbol of disorientation.

An amazing experience that entraps audiences in its slippery, fog-ridden world, Gan Bi will ascend to the pantheons of world cinema, informing the audiences of his distinction from all other filmmakers for years to come. Look out for news on any and all of this up and coming artist’s work going forward.

Author Bio: Zach Crosswait is a filmmaker operating out of Chicago. He is currently studying cinema at Columbia College of Chicago, he regularly posts work on YouTube.