14. Suzaku (Naomi Kawase,1997)

Naomi Kawase’s first feature film established her as an international sensation, since she won the Caméra d’Or at Cannes, and a number of other international awards.

The film revolves around the lives of six teams of elderly people living in the Yoshino Mountains. Avoiding analysis and any kind of comments, Kawase lets the story speak for itself. In that fashion, she presents a portrait of these people’s lives, which borders on being a documentary. In a truly harsh environment, the optimism and courage of these people are exemplified, along with their evident melancholy.

Masaki Tamura’s minimalist cinematography is also astonishing.

13. Cure (Kiyoshi Kurosawa, 1997)

The script revolves around a surge of murders occurring throughout Tokyo. The common elements in the cases are an X carved with blood on the victim’s neck, and the fact that the murderer is found close to the victims, but does not remember a thing. Detective Takabe and psychologist Sakuma are trying to find out what happened, but their research reaches a dead end.

Instead of resorting to plot twists and reversals, Kiyoshi Kurosawa gradually creates a maze that combines terror with confusion, in a tactic that exemplifies the ingenuity of both his direction and writing. This trait becomes quite evident in the final scene, which combines intelligent direction with cunning visuals. The fact that Kurosawa also makes a social remark through the extreme story gives the film additional depth.

Koji Yakusho gives a great performance as Detective Takabe, in an effort that established him as Kurosawa’s regular. The overall style of the film established Kurosawa as the master of slow horror, in a tendency that resulted in a number of masterpieces of the genre.

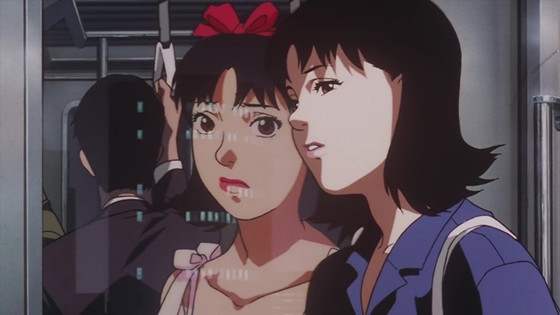

12. Perfect Blue (Satoshi Kon, 1997)

The year 1997 was a milestone in Satoshi Kon’s career for two reasons: the release of this particular movie in theaters, and the initiation of his collaboration with Madhouse Inc., which sheltered his genius until his last birth.

Originally, the script was to be based upon the homonymous book by Yoshikazu Takeuchi; however, after closer inspection by Kon and Sadayuki Murai, the co-writer of the script, they asked and eventually received permission to alter the story.

Mima Kirigoe, a member of the largely popular J-pop band Cham, announces during a concert that this will be the last performance of the band, since she has decided to pursue an acting career. The announcement creates chain reactions in Mima’s life, as much as in the lives of the people near her. A number of her fans become frustrated, regarding her decision as a betrayal towards them, mostly by a known stalker of hers named Me-mania.

In the meantime, she discovers a blog depicting the details of her everyday life, which no one aside from her could experience. Additionally, the blog is updated on a daily basis, presumably by her. She discusses the issue with her manager, who soothes her for the time being; however, as she delves in the blog, she begins to lose her touch with reality.

Furthermore, someone is murdering certain individuals who had helped her with her career. Moreover, she is constantly discovering elements that incriminate her.

Kon focuses on the association between reality and presumed reality, using the archetype of the pop idol as an example. The actual personality of the artist is in contrast to the personality witnessed by the fans, which is the one that becomes apparent onstage.

According to Kon, cinema can undermine reality, revolting against the human mind that almost exclusively receives images from the actual environment. The question he presents is clear: why should an image emerging from facts in the material world be truer than one emerging from the human mind? Kon’s Weltanschauung, which is present in all of his films, resides upon this particular questioning.

Junko Iwao is sublime in the role of Mima; her voice acting is equally magnificent with Kon’s designs.

11. Jin-Roh: The Wolf Brigade (Hiroyuki Okiura, 1999)

Based on the “Kerberos Saga”, an alternate history universe created by Mamoru Oshii, “Jin-Roh” takes place in 1950’s Tokyo, where the insurrection of the people is an everyday event. In order to put down those risings, the government introduces a special police force called Kerberos Panzer Cops. After an explosion during a demonstration, the team is ordered to find and eliminate the terrorist cell responsible, who are hiding in the sewers.

Corporal Kazuki Fuse, during his face-off with an underage female member of the terrorist group, hesitates to kill her, thus resulting in her suicide by detonating a bomb and him subsequently being court-martialed. Eventually he meets the sister of the aforementioned girl and discovers a great secret regarding the forces he serves and a secret group among the ranks of his team, called Jin-Roh.

Hiroyuki Okiura directed a dark and depressing anime that mostly takes place at night, in sewers and basements and generally in non-illuminated places. However, this contributes to the presentation of a highly evocative atmosphere, where the dark side of the characters can easily grow, at times making them function like animals. In that fashion, Okiura makes a clear comment regarding human nature, while exemplifying his pessimism.

The drawing is elaborate, particularly that of the general appearance of the Kerberos team, which aims and succeeds in creating fear in the viewer. Furthermore, the characters are realistically depicted, the animation smooth and impressive, and the violence graphic, though sporadic.

10. Kikujiro (Takeshi Kitano, 1999)

Masao is a schoolboy who lives with his grandmother in Tokyo. After receiving a package that appears to pinpoint the location of his long-lost mother, he embarks on a protracted journey to meet her. Kikujiro, played by director Takeshi Kitano, is a neighbor whose spouse forces him to accompany Masao.

In the beginning, Kikujiro isn’t serious about the trip and spends his time gambling, but after the child encounters a molester, he promises to see him safely to his destination. Along their way, they meet a number of peculiar individuals that end up shaping their travel and even their personalities.

The main theme of the movie is alienation and the way that people who experience it respond to it, and that is why all the main characters, including the two main leads, are outcasts and misfits. The message that Kitano wants to gets through to the audience is that those kinds of people, although at constant odds with the “regular” world, can actually find happiness in life if they find other people like them and stick with them.

This was the first time Kitano succumbed to criticism for the violent elements in his movies, deciding to shoot a road movie without any violence at all. In that fashion, “Kikujiro” is set up like a child’s school report on what they did on their summer vacation.

With the slow pace and in combination with the lack of violence, “Kikujiro” ends up being Kitano’s most relaxed movie. His peculiar sense of humor is also present, mostly presented through body language, without many words, a practice where Kitano truly excels.

9. Audition (Takashi Miike, 1999)

Quite a historic production (at least for its cult following), since it was the film that established Takashi Miike as a prominent member of the category and Eihi Shiina as a “priestess” of the grotesque.

Based on the novel by Ryu Murakami, “Audition” tells the story of Shigeharu Aoyama, a middle aged entrepreneur, who has recently lost his wife and has been living a disinterested life ever since. His 17-year-old son, Shigehiko, who worries about the turn his father’s life seems to have taken, prompts him to meet new women. Yoshikawa, a friend of Shigeharu and a film producer, proposes that he take part in a sham in order to meet women, an idea to which he agrees.

According to the plan, actresses would supposedly audition for the role of Shigeharu’s wife in an imaginary film, although the actual purpose is for Shigeharu to find someone he could date. Many beautiful women audition, but there is only one who truly stirs his heart, a woman named Asami Yamazaki.

The young woman states that she is a former ballet dancer who was recently working for a music producer. Yoshikawa warns Shigeharu to be careful, since he was not able to cross-check Asami’s background, but he is already blinded by love.

The film begins in the usual Japanese style, with hypnotic rhythm, scarce dialogue, almost no music, and a permeating realism, both in the environment in which it takes place and in the characters. The first hour in particular does not look like a horror film at all, but rather like an indifferent social film.

However, as the story progresses, some out-of-place images shyly make their appearance, which become more frequent as the mystery surrounding Asami increases. In particular, the scenes with her smile and a peculiar sheet give the impression that “something” is about to follow.

Miike took a step away from the J-horror genre that was culminating at the time with films like “The Ring”, “Ju On: The Grudge”, and “Dark Water”, and abstained from incorporating supernatural elements in the film, instead trying to invoke fear with the atmosphere and the subtle feeling of uneasiness that permeates it. Some sense of surrealism remained, but it is of minor importance.

The ending scene is one of the most dreadfully realistic to ever appear in cinema, and an outcome that benefits the most from the film’s sound and the otherwise cute exterior of Asami.

8. Ringu (Hideo Nakata, 1998)

Based on the homonymous novel by Koji Suzuki, this film was the one that turned the global audience’s attention toward J-horror, creating a franchise that spawned two sequels, three spin-offs, and a Korean and two American adaptations.

The script revolves around a videotape that causes anyone who watches it to die in seven days. Journalist Reiko Asakawa and her ex-husband investigate the case, only to stumble upon Sadako, a creature with a sad and mysterious story, who still exists somewhere between nightmare and reality.

Hideo Nakata presented a social message regarding technophobia and a fear of the media, while building a great story using horror as the main ingredient. Sadako’s exit from the television is a clear example of the two, and is one of the most iconic (and horrific) images of the genre.