7. The Big Sleep (1946)

Howard Hawks’ film adaptation of Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep gleefully celebrates the hardboiled private eye Phillip Marlowe (Humphrey Bogart) in what is arguably considered the definitive take on this iconic figure. Marlowe swiftly manoeuvres a bleak film noir landscape of betrayal, perversion, and murder with hugely entertaining results.

“So, you’re a private detective,” says Vivian (Lauren Bacall) with a nonchalant verve in the first of many verbal duels. “I didn’t know they existed, except in books, or else they were greasy little men snooping around hotel corridors. My you’re a mess, aren’t you?”

The savage wit on display is par for the course in this cinematic treasure, and the twisty plot is so convoluted and Byzantine that Hawks famously asked Chandler for the identity of the killer. Chandler admitted he was never sure himself. Ha!

6. Zodiac (2007)

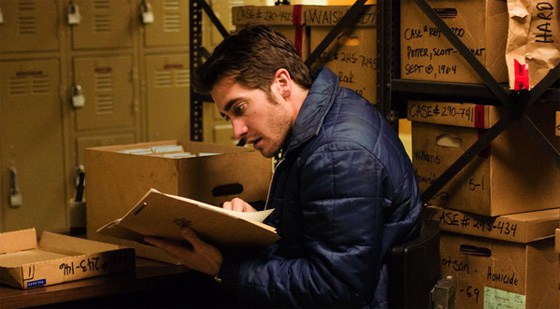

David Fincher’s Zodiac, arguably his first real masterpiece, confounds audience expectation by presenting a story lacking closure, and yet is still incredibly gripping throughout.

Based on the true story of the ill-famed serial killer and the protracted manhunt he roused that ultimately lead nowhere, Robert Graysmith (Jake Gyllenhaal) is a San Francisco Chronicle political cartoonist – upon whom’s non-fiction book of the same name the film is based – who may just have figured out a way to crack the encrypted letters that the Zodiac has been taunting police and media with, pertaining to his past and future crimes.

Gyllenhaal is mesmerizing as Graysmith, and leads a strong ensemble cast that includes Robert Downey Jr. as crime reporter Paul Avery and Mark Ruffalo as SFPD Inspector David Toschi (also in the A-list cast are Brad Pitt, Brian Cox, Elias Koteas and Chloë Sevigny).

For all it’s shaggy-dog digressions, and misleads, Fincher shows an amazing amount of stylish restraint in what adds up to a startling, discomfiting, and troubling tour de force.

5. Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975)

Based on the 1967 Gothic novel by Joan Leslie, itself purportedly stemming from a troubling true story, Picnic at Hanging Rock is an experiential masterpiece from Peter Weir. Hanging Rock is a geological formation in central Victoria, Australia, and the film unfolds on Valentine’s Day, 1900.

A group of girls––19 students and two teachers––from a strict boarding school, Appleyard College, enjoy a day out and the titular picnic. During the dalliance three of their number and one of the teachers simply vanish without a trace. A week later one of the missing girls is found unharmed, and with no recollection of what’s gone on.

Weir’s brand of unsettling cinema was a huge arthouse success and, coupled with Russell Boyd’s inspired and elegant cinematography, has been baffling and betraying audiences ever since its release.

A haunting mystery, a fever dream of youthful, fragile femininity and buried sexual hysteria, there may well be no other film as poetic, problematic, nostalgic and haunting as this one, and with so aching a mystery with no answer.

4. The Vanishing (1988)

George Sluizer’s Dutch chiller is a tightly wound, harrowing ordeal that’s full of sinister surprises. Based off of the 1984 novella The Golden Egg by Tim Krabbé (who co-wrote the screenplay with Sluizer), the uncompromising finale is one of the most startling in cinematic history, and is certainly what led Stanley Kubrick to refer to The Vanishing as “the most horrifying film I’ve ever seen”.

Rex Hofman (Gene Bervoets) and his girlfriend, Saskia Wagter (Johanna ter Steege), are travelling through the quaint countryside of Southern France when they make a seemingly innocuous stop at a gas station. It’s there, in broad daylight, when Rex’s back is turned, that Saskia disappears. Finding her will be an endeavor that will consume Rex, and years will pass before he gets closer to the tragedy.

Anyone who’s seen The Vanishing would agree, it has perhaps the most unsettling ending of any film, just be sure to avoid the 1993 remake.

3. Memories of Murder (2003)

Bong Joon-ho (Snowpiercer) rose to international fame, as did his lead actor Song Kang-ho, in this startling South Korean thriller that, like many films on this list, is based off of actual events. Memories of a Murder begins in the autumn of 1986 when a woman’s body is discovered in a field outside of Hwaseong, a city fringed by bucolic fields and farmland.

Local detective Park Doo-man (Kang-ho) is out of his depth with the brutal crime – soon to be the first of several – and his bungling, ill-equipt team are soon bolstered by Detective Seo Tae-yoon (Kim Sang-kyung) from the mean streets of Seoul.

The film, a favorite of many auteur-adoring critics and filmmakers alike, including Quentin Tarantino, is wonderful and wise mixture of police procedural, detective film, black comedy, and social satire. It’s an elusive, at times frustrating film – the real-life crimes and those in the film never get satisfactorily solved – Memories of a Murder is one of the freshest and most formal serial killer films around, with enough surprises and shocks to keep viewers riveted and rattled until its final polished frame.

2. Rashomon (1950)

This lyrical and legendary masterpiece from Akira Kurosawa tells the judiciously straight-forward tale of Tajōmaru, a bandit (Toshiro Mifune) who’s charged with murdering a Samurai (Masayuki Mori) and then raped his wife (Machiko Kyo).

Nothing is as it seems though, and things get gradually more complex as the wife, the fallen Samurai—who communicates via a medium named Miko (Noriko Honma)—and also a bystander (Kichijiro Ueda) who bore silent witness, each relate their own distinct versions of the tragic events.

Part of this great film’s legacy, apart from establishing what’s now the archetype for unreliable narrators, is the coining of the term “ the Rashomon effect”, which refers to real-world situations wherein numerous eye-witness testimonies of an event often contain conflicting information.

1. L’Avventura (1960)

Michelangelo Antonioni’s L’Avventura is an aloof and artful masterpiece of existential dread, ennui, alienation, and a missing woman who is never recovered.

The film opens with Anna (Lea Massari) and her friend, Claudia (Monica Vitti) in a villa outside of Rome. They are soon joined by a circle of friends including Anna’s beau, Sandro (Gabriel Ferzetti), and soon en masse they all board a yacht bound for Lisca Bianca. Antonioni, an artist of great breadth, quickly shatters the expected three-part story structure when, at the close of the first act, Anna disappears without a trace.

Claudia and Sandro embark on a half-hearted search for Anna, more a grand gesture really, as neither seem capable of solving the mystery. Not only do they have little to go on, their jaded tendencies seem to stymie their advances (except perhaps their advances on one another). Their search becomes an impotent one, though one that unfolds with grace and understanding.

L’Avventura won Antonioni the Jury Prize at Cannes that year, and established Vitti as an icon of Italian cinema. So explicit and painterly was Antonioni’s canvas-like frames that he elevated pop art to high art.

The final image of the film is unforgettable; Sandro seated on a bench, leaning against Claudia, who stands over him, with the Stromboli volcano imposing itself upon them in the distance, cold and cruel.

This profound end scene has struck a resonating chord with audiences the world over and Martin Scorsese famously said it was “one of the most haunting passages in all of cinema, Antonioni realized something extraordinary: the pain of simply being alive. And the mystery.”

Author Bio: Shane Scott-Travis is a film critic, screenwriter, comic book author/illustrator and cineaste. Currently residing in Vancouver, Canada, Shane can often be found at the cinema, the dog park, or off in a corner someplace, paraphrasing Groucho Marx. Follow Shane on Twitter @ShaneScottravis.