7. The Stepfather (1987)

Terry O’Quinn gives a career-defining performance as Jerry Blake, who marries widows and divorcees in the hope of finding the perfect family then erupts into violence when they fail to live up to his expectations.

When we first see O’Quinn, he’s picking up the pieces after his latest spree, stepping over the dead bodies of his family before changing his appearance and leaving the scene for good. The movie follows him to a new town, but Donald Westlake’s screenplay is too thoughtful to paint him as a one-dimensional villain.

For that, you have to watch the 2009 remake, which rebooted the character for the Twilight demographic. Told through the eyes of the hunky male lead, the story throws in every cliché possible, from incompetent cops to impossibly wise teenagers, and tops it all off with a rooftop showdown set during a storm.

6. A Nightmare On Elm Street (1984)

By 1984, the slasher genre seemed played out until Wes Craven added a supernatural element and introduced Freddy Krueger, a horror villain just begging to given his own franchise. Not only did his name bring to mind Krug from The Last House On The Left, but Craven would throw in more of the is-it-a-dream-or-isn’t-it sequences he’d first used in that movie.

Freddy is perhaps the best known horror movie villain of the 1980s, so famous that he appeared in music videos and on lunchboxes, and seemed to be on the cover of Fangoria every other month whether he had a movie out or not. In his debut, though, he isn’t much of a punster and remains mostly in the shadows, stalking a bunch of teenagers (including Johnny Depp) in their dreams before slashing them to ribbons.

For a movie from the MTV-obsessed, short attention span 80s, the level of invention shown here is remarkable, and the movie boosted the careers of Craven and Robert Englund, the latter of whom became a sort-of modern day Boris Karloff. It’s too bad that New Line Cinema rushed the sequels, cranking one out nearly every year until 1990, by which time the genre had once again run its course.

5. Saw (2004)

From the moment Adam (Leigh Whannell) wakes up in a windowless room, you know that Saw is going to be very different from your average slasher movie – it’s smarter and sharper, with a script you could cut diamonds on.

This first film isn’t really about the traps or about Jigsaw – when it opens, it seems like it’s going to be another of those boring two-guys-in-a-room indie thrillers. Then Leigh Whannell’s script whisks us out of the room and straight into the story of a killer who offers his targets a choice – confront your worst fears, or die.

His preferred method of rehabilitation for drug addicts is the “reverse bear trap”, which, unlike in the sequels, is never deployed and actually “helps” its target. Someone give that man a franchise and a cool-sounding name – something like Jigsaw ought to do it.

It’s unfair to claim that Saw initiated the trend for so-called “torture porn” – that dubious honour rests with Michael Bay’s equally dubious Texas Chainsaw reboot, which also treated us to the sight of Jessica Biel in a wet t-shirt. In contrast, Saw was a movie for the head, a well thought-out psycho-thriller that didn’t skimp on character.

4. The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974)

Released in the same year as Black Christmas, Tobe Hooper’s film is if anything even more economical and effective than Bob Clark’s movie, eschewing cheap jokes and focusing on its teenage leads without cutting away to uninteresting supporting characters. It’s also the more suspenseful of the pair, and when British censors failed to reduce its air of claustrophobic dread with cuts, they resorted to banning the film until 1999.

Not only does Hooper proved a virtual textbook on how to ratchet up tension, he also has a nice line in black humour, and his family of cannibals are a grimly amusing parody of a soap opera family. There’s the long-suffering man of the house, whose attempts to keep the family business running are undermined by his two idiot sons, most notably Leatherface, who despite his astonishing build and strength (and mask made from human skin) isn’t smart enough to figure out where all these teenagers keep coming from.

Despite the perfect title for a trashy Drive-in movie and a tagline (“Who will survive and what will be left of them?”) that promises gore galore, Hooper shows very little in the way of blood, something his detractors and his imitators alike often forget. His film is less interested in an endless succession of lopped-off limbs than in studying how his characters hold up in these extreme situations, making the movie the ultimate endurance test.

3. Peeping Tom (1960)

Peeping Tom opened shortly before Psycho in the UK – and promptly wrecked the career of its director. In 1960, Michael Powell was the much-lauded co-director of The Tales Of Hoffmann, A Matter Of Live And Death and The Red Shoes, but here he was directing a sleazy film about a photographer who murders women and captures their expressions on film. Had he lost his mind?

It may involve a psychopathic killer, but Powell’s film couldn’t be more different from Psycho. It’s a cold, detached film that never skimps on the portrayal of London’s seamier side. The first scene shows the main character meeting – and then murdering – a prostitute, which is very different from Psycho’s “controversial” shots of Janet Leigh in her underwear.

Grim and unrelenting, this is by no means a “fun” picture, but it appears to have influenced Hitchcock’s later career. Returning to London in 1972 to shoot Frenzy, Hitch not only cast Anna Massey, Peeping Tom’s lead actress, but when it came to staging the first murder, Hitch showed it in full close-up, just like Powell.

2. Halloween (1978)

John Carpenter’s film isn’t about plot; like the Italian giallo films to which it owes a debt, it’s all about the mastery of cinematic technique.

From its opening tracking shot, inspired by Orson Welles Touch Of Evil, Halloween has more on its mind than appealing to the lowest common denominator. The use of Panavision, unusual in a cheap horror movie, made the suburbs, usually the bastion of middle-class security, seem sinister, while every empty space became a potential hiding place for the film’s masked assailant. Carpenter knows that it’s all a game, so he delays the anticipated shock by revealing nothing when there should be something and orchestrates some terrific knee jerk scares by having his bogeyman emerge from the darkness.

Despite its limited budget and shooting schedule (and being shot during a Californian summer), Halloween has a terrifically eerie mood that few other horror pictures can match.

The speed of the narrative glosses over all the logic loopholes (despite having been incarcerated since the age of six, Michael Myers has no problem commandeering a car at a moment’s notice) and Carpenter manages to scare his audience without being inordinately nasty. By no means an unsophisticated filmmaker, he exhibits all the taste and judgment that his imitators lack.

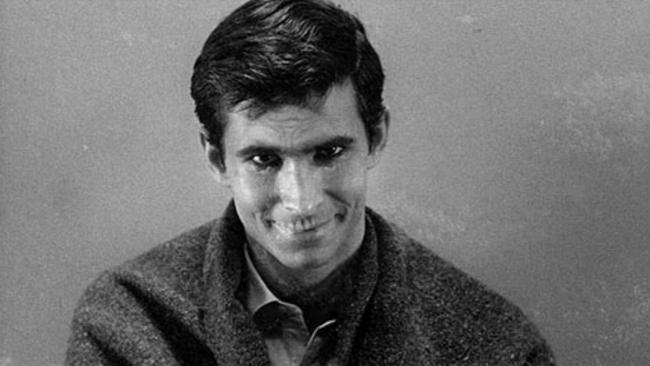

1. Psycho (1960)

Mindful of the success that studios such as AIP were enjoying with low budget exploitation films, Alfred Hitchcock set himself a challenge: turning his back on star-studded, multi-million dollar blockbusters such as North By Northwest, he’d direct an exploitation picture of his own, only with decent actors, a quality script and his trademark visual flair.

Despite being turned down by Paramount, which forced him to shoot on the Universal lot using the crew from his TV show, the gamble paid off and Psycho became one of his most successful pictures. It was also the movie that took the horror film out of European castles and placed it squarely in the middle of America, where one of cinema’s most famous killers operated a run-down motel.

Based on notorious serial killer Ed Gein (“The Wisconsin Ghoul”) and Castle Of Frankenstein editor Calvin T Beck, Norman Bates isn’t a vampire, a mad scientist or a disfigured criminal, he’s a seemingly ordinary (if socially maladjusted) young man, and one of the most important characters in horror cinema. From now on, filmmakers wouldn’t shy away from placing their stories in everyday settings.