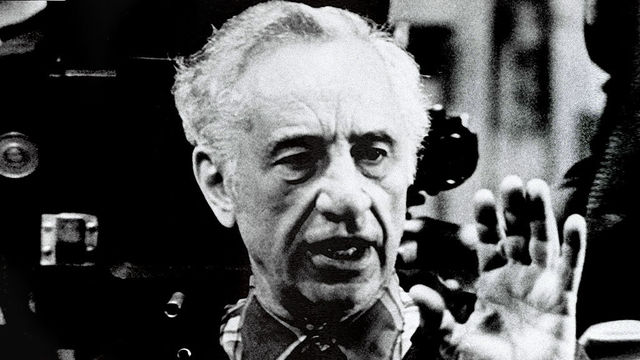

7. Elia Kazan

Films: A Streetcar Named Desire; East of Eden; On the Waterfront; Gentleman’s Agreement

Born in Istanbul when the city was the capital of the Ottoman Empire, Elia Kazan emigrated with his family to the U.S. when he was four years old. He attended the Yale University School of Drama and worked as a stage actor and director, with two Tony Awards for Best Director.

Fox invited him to Hollywood to direct “A Tree Grows in Brooklyn” and Kazan identified himself with the Irish immigrant family that resides in New York and their concerns. He directed a string of successful films, most of the time preferring unknown actors and working with them using ‘method’ acting, being himself, first of all, a theater director. Marlon Brando and James Dean, good examples of ‘method’ actors, were introduced by him to movie audiences.

Most of his movies treated social topics – anti-Semitism, corruption in politics and unionism – or reflected aspects of his personal life – culminating by the semi-autobiographical “America, America.” He won two Oscars for Best Director and directed 21 actors to Oscar nominations, with nine of them winning the awards.

However, his testimony in 1952 before HUAC cost him many friends he had among Hollywood artists and writers. Even when, in 1999, he was awarded a honorary Oscar, many actors present at the ceremony preferred to not applaud.

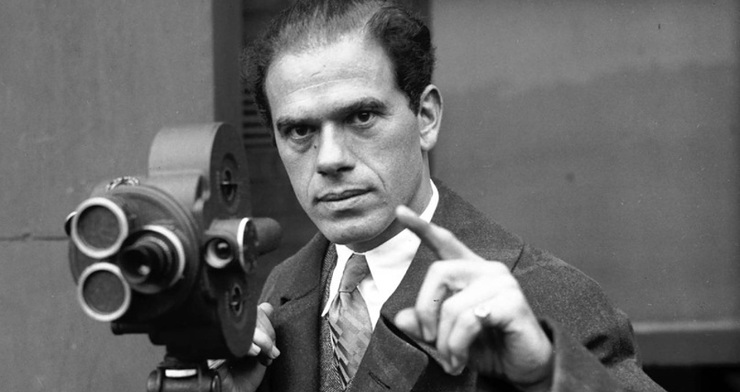

6. Fritz Lang

Films: Contempt; The 1000 Eyes of Doctor Mabuse; Hangmen Also Die

Born in Vienna at the end of the 19th century, Fritz Lang studied at the Technical University and then fought in World War I. When he came back, he decided that what he wanted to do was make movies, and he went to Berlin to work in UFA.

There he became member of the group of expressionist directors and filmed some pictures that are nowadays part of the curriculum in every decent movie seminar: “Destiny,” “Dr. Mabuse: The Gambler,” and the futuristic dystopia “Metropolis,” which influenced many directors, from James Whale to Ridley Scott in “Blade Runner,” and led UFA to bankruptcy. When expressionism lost its dynamics, he turned to the ‘New Objectivity’ movement and filmed “M,” a masterpiece that depicts life in the dark side of the city and launched the later famed serial killer genre.

When the Nazi Party came to power, the Reich Minister Goebbels called him to his office to explain him why he pulled his last film “The Last Will of Dr. Mabuse” from circulation and kindly reminded him of a distant Jewish progenitor. Lang left the same night from Berlin and, after a short stop in France, he went to Hollywood to search for work.

His Hollywood career was boosted by two big hits, “Fury” and “You Only Live Once,” but when he tried to work on a comedy musical with his compatriots, Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill, he faced failure and he had to turn to westerns, a genre which he learned to love, in order to keep working. In the 40s, he came back to directing noir films, “Scarlet Street” being the most famous of them, and in the 50s he gifted Hollywood with late expressionistic noir classics such as “The Blue Gardenia” and “The Big Heat.” However, he got tired of the way studios worked there and went back to Berlin in 1958 to release his last two films.

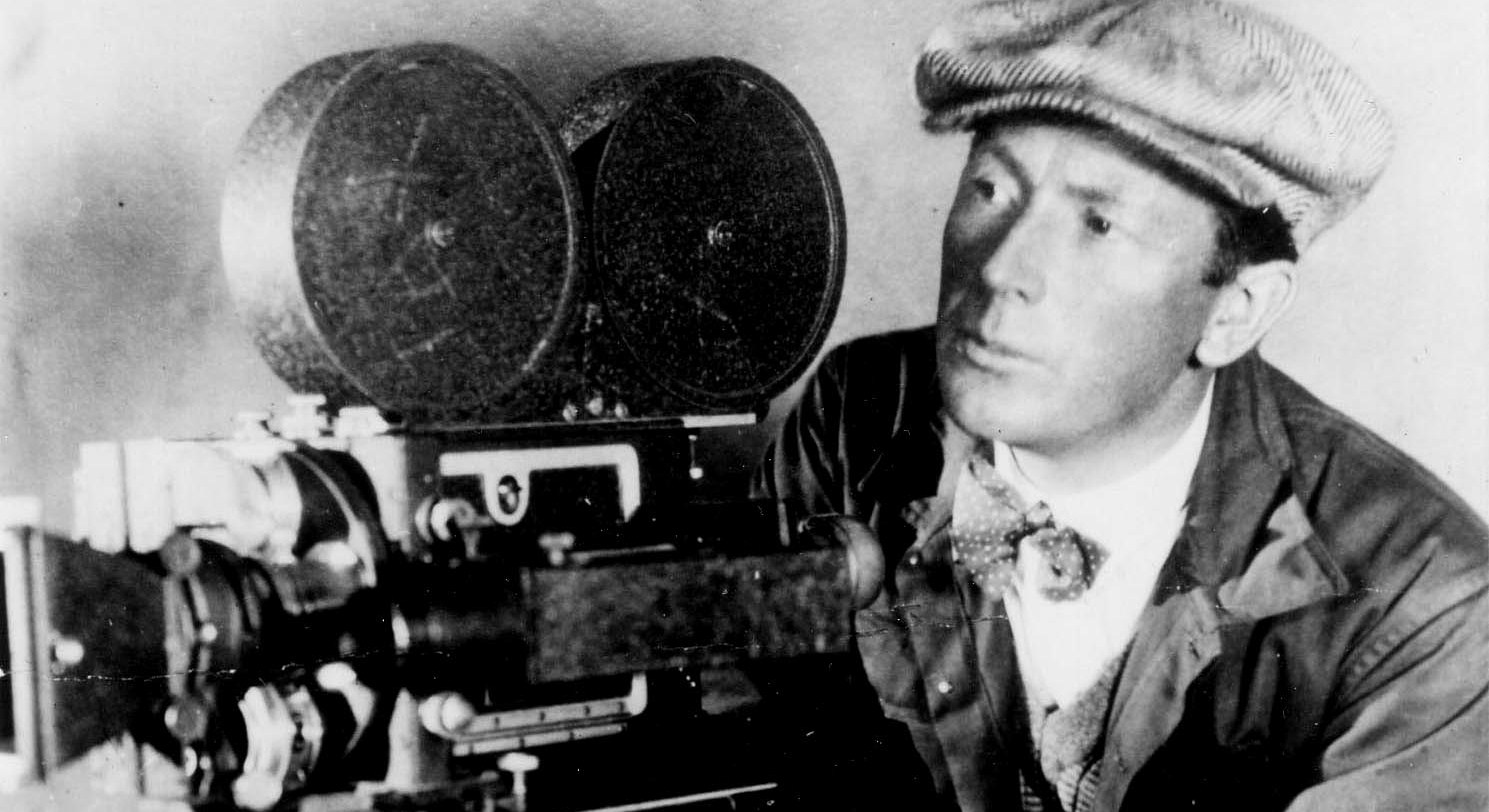

5. Frank Capra

Films: It Happened One Night; You Can’t Take it With You; Mr. Deeds Goes to Washington

Frank Capra’s parents emigrated from Sicily to California with him and his six siblings when he was five years old. Having led a very poor childhood, he became rich and famous personifying, in a way, the American Dream.

As a boy, he did all kinds of jobs in order to earn money for his family. When he was almost penniless and had a job selling books, he saw an ad about a small studio in San Francisco and he called saying he already had experience in Hollywood. His first job was to shoot a film in two days with the help of a cameraman. After awhile he went to Los Angeles to work with Frank Cohn in the studio that would later be Columbia Pictures.

Capra preferred sound films and he easily learned how to use the new technologies. In the 30s he directed screwballs that swept the Oscars. When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, he collaborated with the U.S. Army and produced a series of documentaries called “Why We Fight,” to enhance the morale of the soldiers.

After the war he directed the classic “It’s a Wonderful Life,” but his career seemed to fade because, as people in the film business commented, he could not easily adapt his ideas and way of filming to postwar prosperity. For Capra, it was the tactics of HUAC – though he was not called to testify – and the rising power of the stars over the directors that drove him away from cinema, which he devotedly served for three decades.

4. F.W. Murnau

Films: Sunrise; City Girl; Faust

The ultimate master of the silent era cinema was born in Westphalia in 1888. Since his adolescence, he read the works of Nietzsche, Schopenhauer, Ibsen and Shakespeare, and later he studied in Berlin next to theater director Max Reinhart. After surviving seven crashes as an Air Force pilot in World War I, he returned to Berlin and became one of the pillars in the expressionist movement in cinema, with his “Nosferatu” considered among the masterpieces.

In his film “Der Letzte Mann,” he plays with his camera according to the Kammerspiele theory in an effort to ‘see’ with the eyes of the protagonist, leaving expressionist elements in the background. The movie was a great success in America and thus he obtained a contract with Fox.

His first film in U.S., “Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans,” won the first Best Picture Oscar and is considered by many as the best silent movie ever. According to Dave Kehr, “The miracle of Murnau’s mise-en-scene is to fill the simple plot and characters with complex, piercing emotions, all evoked visually through a dense style that embraces not only spectacular expressionism but a subtle and delicate naturalism.”

After two sound films that were not well received, he traveled to Bora Bora with documentarist Robert Flaherty to shoot his last masterpiece “Tabu – A Story from the Southern Seas.” One week before its opening, Murnau died in a car accident.

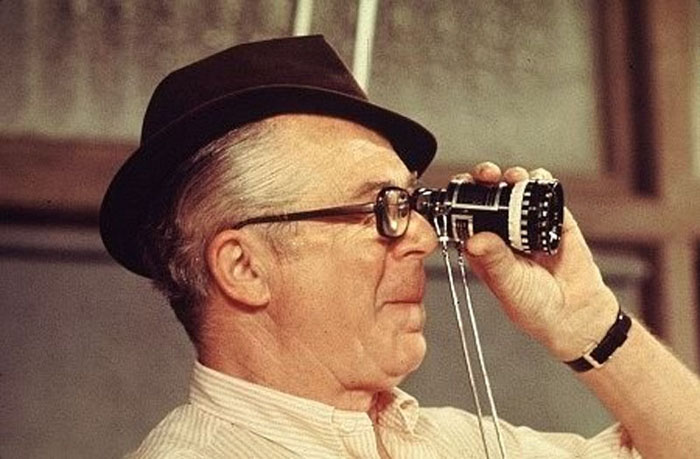

3. Billy Wilder

Films: The Lost Weekend; Sunset Boulevard; The Apartment; Some Like it Hot; Sabrina

Billy Wilder was a Jewish journalist and script writer in Berlin who rushed to flee Germany when the Nazis assumed power. He stayed in France sending scripts in Hollywood until he got a positive answer. He arrived in Los Angeles in 1934 to work for the first years as a script writer, with “Ninotchka” being his best work, until he persuaded Paramount to let him direct “The Major and the Minor.” His third film, the noir “Double Indemnity,” was a major hit that consolidated Wilder’s position among Hollywood directors.

Other hits followed as Wilder made the transition from studio director to independent auteur who released great movies during the 50s and the 60s. He was never afraid to touch painful social topics, such as alcoholism, gutter journalism and material consumption, and he was awarded with six Oscars, a Career Golden Lion, and many other awards and nominations.

His last works, though not highly appreciated, are considered the most ‘European’ ones. Leaving a deep mark in Hollywood history, he was considered as the last link to its classic era.

2. Charles Chaplin

Films: The Kid; The Gold Rush; City Lights; The Great Dictator; Monsieur Verdoux

If ‘rags to riches’ was written to describe only one person’s life, that life would be that of Charles Chaplin, perhaps the most iconic figure in Hollywood history. Born in England by music hall entertainers of Romani origin, he had early enough to face life on his own, as his father had deserted him and his mother was committed to a mental asylum when he was nine years old. His alcoholic father and his mentally ill mother, however, had inculcated in him that he was talented and made him enter a travelling theater group.

Doing any kind of job in order to survive, when he was 14 he searched for an agent that could find him a job as an actor. By 16 he was working as a comedian. In his second tour in the U.S. with a vaudeville troupe, he impressed a representative of Keystone Studios who proposed he sign with them.

Chaplin liked the idea of playing in movies and he stayed in the U.S. His first salary was $150 a week. Four years, many short films and three firms later, in 1916 his salary was raised to $670,000 a year, a change that illustrates the astonishingly growing popularity of the young comedian. Each new contract gave him more creative freedom, making him one of the first auteurs in American cinema.

He directed his first feature in 1918 and he continued releasing jewels of silent cinema – now with his own company, United Artists – until 1936, when the success of “Modern Times” proved that Chaplin’s caliber allowed him to make silent movies in the sound and speaking era just the same. He then started to produce sound movies that apparently annoyed the U.S. government for their political stances.

Chaplin was not welcomed in McCarthy’s Hollywood. After facing a fierce campaign that compromised his reputation, he self-exiled to Europe, where he made two more movies, and returned to United States only 20 years later to receive his Honorary Academy Award from Jack Lemmon in 1972.

1. Alfred Hitchcock

Films: Psycho; Rear Window; Vertigo; North by Northwest; Dial M for Murder

Alfred Hitchcock was born in Essex, England. He studied engineering and started writing short stories while he was working in an electrical cable company. Very soon he got involved in the cinema industry and directed his first film – an unaccomplished project – in 1922, at the age of 23. He met success with his first thriller “The Lodger” and in 1930 he started working with Gaumont – British.

Progressively, he was dedicated to thrillers, a genre he would serve better than anybody, and developed his own style. He used his shots and montages so that the spectator could catch the thoughts of the protagonists, used famous landmarks as a backdrop for suspense, and was characterized by his humor.

Even though the films of that era were successful – “Sabotage,” “39 Steps,” “The Lady Vanishes” – their low budget prohibited his artistic ambitions, so he decided to move to Hollywood and seek more reliable financing. In 1939 he signed a contract with Selznick and shot “Rebecca,” which won the Oscar for Best Picture. That was the beginning of a five decade career.

The ‘Lord of Suspense’ was fan of the Soviet Montage School; he was obsessed with details and the plots of his movies spinned over the same motive: the innocent man plunged in guilt and suspicion, the mentally deranged woman, the attractive, immoral assassin, the monotonous setting where tension lurks. The fact that he was consistent in his topics and the way of filming was evidence, for European critics, of the auteur theory: a director working under the conditions imposed by Hollywood studios could master his oeuvre.

Though some of his more than 60 films are in high positions on many lists – he has five films among the 250 most highly voted on IMDb, more than any other director’s movies – none of them received an Oscar for Best Picture or Best Director.

Author Bio: Regina Zervou is cultural sociologist who took some fifteen years to move from carnival and popular culture studies to cinema theory. An afficionado of movies since she was twelve, she loves the way reality and ‘surreality’ is depicted on the screen. When not watching movies, she loves walking the dogs, swimming, cooking for her children or traveling someplace in Africa or South America to take some pictures.