8. Wendy and Lucy (2008)

This humble, heartrending and lamentable third feature from Kelly Reichardt, whom writer Scott Littman of Senses of Cinema has dubbed “the poet laureate of the Pacific Northwest”, is an understated and breathtaking showpiece.

Writer-director-editor Reichardt, inspired by the short story “Train Choir” by Jon Raymond (who co-wrote the screenplay with her) revisits some neo-realist territories (think Vittorio De Sica’s heart-tugging dog-loving epic Umberto D.) in this life-affirming tearjerker that earns each of those tears with absolute honesty and nobility.

Michelle Williams is brilliantly wonderful as Wendy, a young, broke drifter travelling to Alaska in search of work, solo save for her dog, Lucy. When her junker car finally kicks it in Oregon things get even bleaker when Wendy is busted shoplifting dog food. After finally struggling to post bail Wendy is next faced with the sad fact that Lucy is now missing.

Florida-born, New York-based filmmaker Reichardt may well have her understated masterpiece with the moving miracle, but her entire oeuvre makes for an austere yet ravishing tapestry of forlorn and disparate figures as in her revisionist Western from 2010 Meek’s Cutoff or her most recent and widely acclaimed small-town drama Certain Women (2016), both of which are honorable mentions on this list.

7. Morvern Callar (2002)

Morvern Callar is Lynne Ramsay’s miraculous second feature, a loose adaptation of contempo-beat Scottish writer Alan Warner’s 1995 cult novel of the same name. A challenging but rewarding film of startling beauty and immense intellect, Morvern Callar begins in a small coastal town in the west of Scotland where self-effacing clerk Morvern (Samantha Morton, incredible) is suddenly thrust into turmoil after the suicide of her boyfriend.

A series of rivetingly rendered events soon finds Morven and her bff Lanna (Kathleen McDermott) on a trip to Ibiza and beyond that brings with it unexpected emotions, revelatory questions and comments regarding sexuality, class conflict, loyalty, identity, and lamentation all contribute to a many-layered parable that’s also a stunning tour de force.

“Where are we gonna go?” asks Lanna, to which Morvern responds: “Someplace beautiful.” Ramsay’s Morvern Callar is truly such a place.

6. There Will Be Blood (2007)

Paul Thomas Anderson’s ruthless masterpiece, There Will Be Blood is the stuff of which classics are made. Any discussion of this film must pivot around its scene-stealing and deservedly award-winning star, Daniel Day-Lewis. As infamous oil baron Daniel Plainview, Day-Lewis is a hard-hearted force of nature, and watching this monster-in-the-making is compelling, particularly in the film’s early scenes which are also greatly serviced by the rattling score from Radiohead’s Jonny Greenwood.

A close-fisted, greed allegory, There Will Be Blood has literary origins—it’s loosely adapted from Upton Sinclair’s 1927 novel, Oil!—and is thick with symbolism and cutting edge ideas of sound and sound design. It tops best of lists the world over for good reason.

“Now, my straw reaches across the room and starts to drink your milkshake.”

5. Yi Yi (2000)

Edward Yang’s poignant family portrait, Yi Yi (A One and a Two) is a rich, rewarding, and unforgettable cinematic experience that spans three generations of a Taipei family. While the film certainly takes its time to unfold, it doesn’t waste a moment of its three hours run time, in what may be Yang’s most accessible and engaging film.

In contemporary Taiwan the lives of the Jian family are examined via the alternating perspectives of three family members; the father N.J. (Nien-Jen Wu), the teenage daughter Ting-Ting (Kelly Lee) and the photography-obsessed eight-year-old son Yang-Yang (a wonderful Jonathan Chang).

Unsatisfied with the direction of his current job at a failing computer company, N.J. attempts change as well as reacquainting with a woman (Ko Su-yun), a lost cause love interest from his distant past. Meanwhile Ting-Ting and Yang-Yang contend with the various trials of youth, all while tending to N.J.’s mother-in-law (Tang Ru-yun), who lies in a coma.

As in his previous work, Yang’s cast is populated almost entirely with non-actors, and the performances he elicits have an honesty and an impact lacking in this sort of moving melodrama. Yi Yi is in a class all by itself.

4. I’m Not There (2007)

Todd Haynes’ I’m Not There is a magical one-of-a-kind film “inspired by the music and the many lives of Bob Dylan”, that doubles as an extended in Dylanology. Featuring no less than six actors (among them Cate Blanchett, Marcus Carl Franklin, Richard Gere, and Heath Ledger) as aspects of Dylan’s multifaceted self, the resulting film is an unconventional, inventive, and absolutely beaming musical rollick spanning the five intoxicating decades of Dylan’s entertainment career.

Displaying a gobsmacking supply of contrasting visual styles, unique and varied editing techniques, and lionhearted performances from a virtuoso cast (Blanchett’s brilliant performance deserved all the acclaim and awards it mustered) is just gravy to this delicious eye feast experience.

I’m Not There is the ultimate and most authentic compendium of Haynes’ tremendous work. It’s a moving movie that provokes laughter, tears, elation, and endless revelation.

3. Mulholland Drive (2001)

For all its dark detours, and there are many, David Lynch manages to break chains of anguish and upset with odd ecstatic ardor, capturing, so often, a world of ravaged sensitivity with Mulholland Drive.

Notably with this film, Lynch has handed Naomi Watts’ first major role — which she knocks out of the park — one she embraces with an operatic élan of emotional extremes. Never before has Lynch’s dream logic been so ecstatically displayed and with such mind-shredding results.

A neo-noir mystery which at times feels like a subversive Nancy Drew-style yarn, the wholesome Betty Elms (Watts) newly arrives in L.A., plans to breakout into acting despite her extreme, almost comical naiveté. Betty soon meets Rita (Laura Harring), with whom she becomes fast friends and roomies, oh, and there’s Diane (Watts), a waitress, who looks just like Betty, amongst others in a Lynchian chorus of late-night and sun-soaked chimera-like characters.

An often upsetting film, anxieties and fears accumulate in staccato sequences rendered in punishing tableaux, begging the question: is what we’re seeing Betty/Diane’s death dream? Perhaps a better question is who’s-dreaming-who?

Mulholland Drive offers up sublimated desires, dual identities and Hollywood satire in a package that may well be Lynch’s finest work, or his most irksome, depending who you ask. Regardless of this, the dreamlike wanderings, intense imagery, comic sidesteps, and eerie instances certainly add up to an rememberable puzzle with alternate realities, danger, provocation, and strange shadows. A pièce de résistance.

2. Spirited Away (2001)

Unlike oh so many mainstream animated films, Hayao Miyazaki constructs imaginative worlds without the condescending expression and over-sentimental characters.

Spirited Away is no exception as it tells the adventurous tale of 10-year-old Chihiro Ogino and her parents on their way to their new home when they take a strange detour and stumble upon a novelty town of objet d’art. The unsettling place they’ve discovered soon becomes populated by spirits, once the sun has gone down. Chihiro must find a way to move amongst the entities, rescue her parents, and figure out a way home.

Taking after literary fabulists from Europe, Spirited Away is Miyazaki’s variation of Lewis Carrol’s Alice in Wonderland, with a dash of A.A. Milne. The hand-drawn scenes radiate with affection, energy, and wild invention.

Miyazaki, with Spirited Away, shares the cultural disparity of his great countrymen, directors who rose to international prominence like Kenji Mizoguchi (1898–1956) and Yasujirō Ozu (1903–63).

Spirited Away is a truly transcendental flight of the imagination, and one steeped in the manga tradition. It also generously offers a compassionate discernment on the ill effects of ecological loss, the perseverance of preparation, of rolling with the punches, the plums of altruism, the force of friendship, and perhaps above all, the gravity of celebrating where you came from and who you are.

This is unmistakably one of the great animated films ever made, and an unbridled revelry.

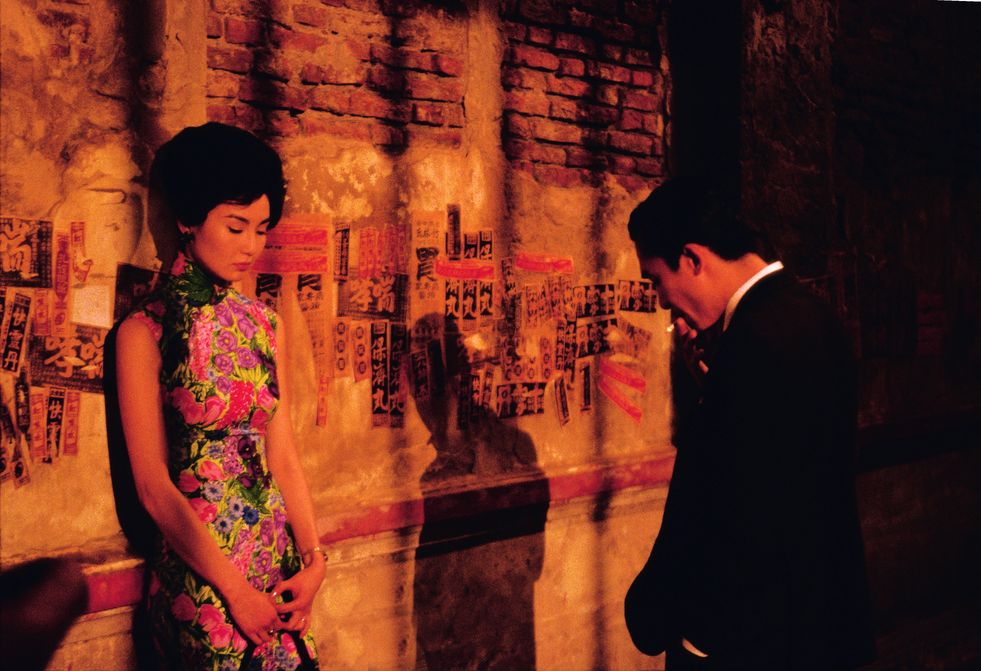

1. In the Mood for Love (2000)

The ashen ache of stolen moments, and the often painful passage of time hangs heavy upon Hong Kong filmmaker Wong Kar-Wai’s 2000 masterpiece, In the Mood for Love. As anthem to the agony and ecstasy of close-lipped affection, this film more than any other in Wong’s considerable oeuvre, is a Proust-like conjuration of memory and misgiving.

The second installment of a rather loose trilogy that began with Days of Being Wild (1990) and concluded with 2046 (2004), In the Mood for Love unravels in Hong Kong, 1962, centering on two neighbors living in a close quarters tenement house. Maggie Cheung and Tony Leung shimmer as Su Li-zhen and Chow Mo-wan, the neighbors in question, who rightly suspect their respective spouses are having an affair.

A painful poetry and sad resignation haunt the pair of potential sweethearts, elegantly framed by superstar cinematographer Christopher Doyle, Wong’s frequent collaborator. Numerous times the camera seems to pry, eavesdropping almost, on the star-crossed couple and their resisted romance.

The period details are perfect and never perfunctory—the cheong-san dresses adorned by Su Li-zhen are heart-stirring in detail and design—the color saturation and play of light is heavenly and mnemonic as is the use of music which conveys and captures an unfeigned nostalgia. The bright colors and unconventional compositions that Wong’s name became synonymous with in the 1990s is here faultlessly fulfilled, even when hemmed in.

As close to perfection as possible, In the Mood for Love renders on an intimate scale the intersection of misery and euphoria, of romance in retrospect, and makes it into cinema’s saddest song of love lost to history.

Honorable Mention:

Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000, directed by Ang Lee), Fat Girl (2001, directed by Catherine Breillat), The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (2001, directed by Peter Jackson), Far From Heaven (2002, directed by Todd Haynes), Oldboy (2003, directed by Park Chan-wook), Birth (2003, directed by Jonathan Glazer), Memories of Murder (2003, directed by Bong Joon-ho), Inland Empire (2006, directed by David Lynch), Let the Right One In (2008, directed by Tomas Alfredson), The Hurt Locker (2009, directed by Kathryn Bigelow), Meek’s Cutoff (2010, directed by Kelly Reichardt), The Master (2012, directed by Paul Thomas Anderson), Amour (2012, directed by Michael Haneke), The Hunt (2012, directed by Thomas Vinterberg), Inside Llewyn Davis (2013, directed by Joel and Ethan Coen), Hard to Be a God (2013, directed by Alexei German), Enemy (2013, directed by Denis Villeneuve), Boyhood (2014, directed by Richard Linklater), It Follows (2014, directed by David Robert Mitchell), Corn Island (2014, Giorgi Ovashvili), The Revenant (2015, directed by Alejandro Iñárritu), Mad Max: Fury Road (2015, directed by George Miller), Toni Erdmann (2016, directed by Maren Ade), The Love Witch (2016, directed by Anna Biller), Moonlight (2016, directed by Barry Jenkins), Certain Women (2016, directed by Kelly Reichardt), Arrival (2016, directed by Denis Villeneuve).

Author Bio: Shane Scott-Travis is a film critic, screenwriter, comic book author/illustrator and cineaste. Currently residing in Vancouver, Canada, Shane can often be found at the cinema, the dog park, or off in a corner someplace, paraphrasing Groucho Marx. Follow Shane on Twitter @ShaneScottravis.