17. Wings of Desire (1987)

Set in West Berlin two years ahead of the collapse of the wall, German New Cinema pioneer Wim Wenders offers up one of his most beguiling, beautiful, and ambitious films, Wings of Desire.

The mostly monochrome film, which is jaw-droppingly gorgeous to look at thanks to legendary cameraman Henri Alekan—Jean Cocteau’s celebrated cinematographer on La Belle et la Bête (mentioned further on down this very list), coaxed from retirement by Wenders—follows two angels, Cassiel (Otto Sander) and Damiel (Bruno Ganz). The angels roam around Berlin, unseen and unheard by humans, and imbued with the ability to listen to the thoughts of anyone and everyone. It’s the ultimate act of voyeurism and it’s never less than completely compelling.

Damiel becomes smitten with a trapeze artist named Marion (Solveig Dommartin) and renounces his immortality in order to return to earth as a human. As a human Damiel loses the ability to eavesdrop on humanity and the film alternates from crisp black-and-white to fanciful Technicolor.

This astonishing film, a high-point in Wenders considerable oeuvre, deservedly won Best Director at Cannes. A masterpiece.

16. Persona (1966)

Persona, rightly earmarked as one of Ingmar Bergman’s greatest films, plays passionately with the idea of the double. Here, Bergman has two actors, Liv Ullmann (in her dazzling debut) and Bibi Andersson, gradually becoming more and more similar to one another over the course of the film, their identities attaching and blurring into one another in a seemingly vampiric vein.

Ullman is Elisabet Vogler, an overworked and exhausted actress in the charge of Nurse Alma (Andersson), who are spending time together in a secluded coastal summer cottage. Slowly a symbiotic relationship manifests amongst them. Bergman has admitted he wrote these roles specifically for them, noting their physical resemblance and chemistry.

As Alma and Elisabet grow closer it becomes progressively less clear whether the two women have joined as one person. Noted filmmaker and writer Susan Sontag has famously described Bergman’s film as a “desperate duel of identities,” suggesting that the discord between Elisabet and Alma is the classical “duel between two mythical parts of a single self” which adds much meaning and magnitude to an already influential and outright exhilarating picture. Persona is pure cinema, a challenge to observe and give order to, to be sure, but one where the rewards are untold and absolute.

15. La Belle et la Bête (1946)

A landmark of fabulist cinematic storytelling from the legendary avant-garde artistic polyglot Jean Cocteau comes the ultimate romantic tragedy, La Belle et la Bête. A reimagining of the classic fairytale Beauty and the Beast, Cocteau’s version was written by Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont and focuses on Belle (Josette Day), who’s father (Marcel André) is sentenced to death for plucking a rose from a garden that belongs to Beast (Jean Marais). To spare her father’s life Belle offers herself to the Beast and from their Beast soon falls in love with her.

Astonishing effects, stunning costumes, overpowering visuals, Henri Alekan’s exemplary lensing, dreamy editing techniques, all pulsing and vibrating to its own fevered, weird, and electrical cadence, it’s a frequently nightmarish and ghoulish tear-jerker. And the chemistry between the two leads is beyond question. La Belle et la Bête is one for the ages.

14. Metropolis (1927)

A bizarre mingling of Gothic horror and science fiction, the highly stylized futuristic utopia of Metropolis is, under the steady hand of director Fritz Lang, equal parts exhilarating and inventive. A close collaboration, previously unheard of, between Lang and his cameramen and designers made pure movie magic with their achievements in bold, dynamic, and startling spatial and visual effects.

This German sci-fi film epic of a paradoxically pretty (to say the least), fully-mechanized futuristic city where an astute, articulate, cultured, and all too-perfect utopia exists atop a bleak and blustery underworld populated by abused and mistreated workers, essentially slaves. An ambitious production that was deliberately intended to rival the Hollywood dream factory

The audience, along with the privileged youthful protagonist Freder (Gustav Fröhlich) uncovers the grimy underbelly and becomes intent on helping the slaves to freedom. Freder befriends Maria (Brigitte Helm), a rebellious teacher, but this tragically puts him at odds with his authoritative father (Alfred Abel), escalating the conflict and the dangers therein.

Pictorially beautiful, with complex and creative special effects that still astound even today, Metropolis is the film that Roger Ebert said “is one of the great achievements of the silent era, a work so audacious in its vision and so angry in its message that it is, if anything, more powerful today than when it was made.”

13. Tokyo Story (1953)

Yasujirō Ozu’s Tokyo Story is a masterpiece of Japanese cinema, and one that regularly finds itself topping best of lists the world over. And while the very relatable tale of the aging married couple Shūkichi (Chishu Ryu) and Tomi (Chieko Higashiyama), and their trip to visit their adult children in Tokyo is one of bittersweet aspirations, adult pain, and profound beauty, often the mastery of the film’s black-and-white photography is ignored.

Tokyo Story exemplifies Ozu’s distinctive camera style perfectly. His “tatami shot” is used to great effect—this is his signature shot wherein the camera is positioned lower than usual, as if the viewer were kneeling in prayer—often lending a subtle yet heroic perspective to the most average and mundane of genuflections.

It’s also been noted by critics and scholars that there is almost no camera movement whatsoever in Tokyo Story, and in keeping with Ozu’s stubborn aesthetic to rarely shoot masters, here the film frequently breaks the 180-degree rule of screen direction, deliberately crossing the axis and making continuity questionable to motivate a stronger, and subtler dramatic impact (the opening scene with Shūkichi and Tomi does this very effectively, setting a tone that reoccurs throughout the film).

A film that asks the viewer to accept a certain sadness and serenity to the human condition, that is not only enormously moving but deeply resonant.

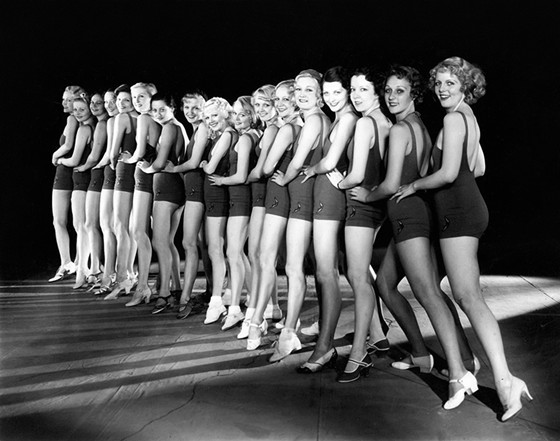

12. Footlight Parade (1933)

Perhaps the greatest of the Warner Brothers Depression-era musicals, Footlight Parade is an exuberant extravaganza that deftly moves under Lloyd Bacon’s direction but then explodes like fireworks on the fourth of July when Busby Berkeley takes the helm for his solid-gold visionary, will-never-be-matched musical numbers.

The plot is pleasant but pedestrian as the wheels of Hollywood have put Broadway director Chester Kent (James Cagney) out of gainful employ until he finds himself a new career producing musical sequences for the silver screen. A competitive field, Chester has only a few days to, along with dreamy assistant Nan (Joan Blondell) and enthusiastic Bea (Ruby Keeler), pull off an impressive contract ahead of some dog-eat-dog competitors. Will they pull it off? With show-stopping numbers like “By a Waterfall” you better believe it!

The art direction of Footlight Parade regularly astounds but all told this film really does represent the zenith of the Busby Berkeley cycle. His work is surprising, head-scratching (as in “how did anyone have the audacity and the courage to pull this off?!”), and even exhausting to witness. There is so much imagination on display that it is impossible not to be swept up, swirled around, and deposited safely to the side, head spinning, when it’s all said, sung, danced, and done.

11. Eraserhead (1977)

Years before the neo-noir nightmare of Blue Velvet and the small town terrors of Twin Peaks, David Lynch gave us the abrasive, bizarro, and surrealist fantasia called Eraserhead.

A pitch-black comedy that’s totally obsessed with body horror, Eraserhead stars Jack Nance as miserable factory worked Henry. Henry’s world is an industrial wasteland made bearable, somewhat, by his girlfriend, Mary X (Charlotte Stewart), who has just had a repulsive mutant child whom Henry is the proud papa of.

The black-and-white imagery Lynch displays is terrific and terribly textured, inherently eccentric, and unsettling as can be. Backed by a deeply disturbing yet elegantly haunting soundscape, Eraserhead helped define the term “Lynchian” while also providing the basis for one of the decade’s most influential and unforgettable midnight movies.

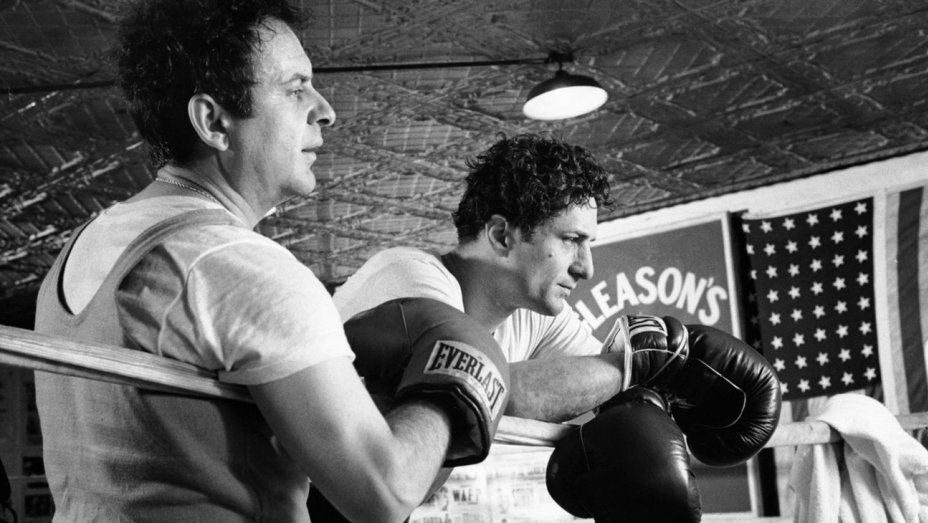

10. Raging Bull (1980)

Perhaps Martin Scorsese’s greatest film, the technically dazzling, and viscerally explosive Raging Bull is the ultimate big screen biopic. The gritty and gruesome story of Jake LaMotta (Robert De Niro), a middleweight boxer rising through ranks, falling in love, and beating both opponents and people close to him (like his little brother Joey [Joe Pesci]) to a bloody pulp along the way, and vicious downward spiral spurned by his toxic masculinity along the way, is the type of movie you crawl away from afterwards.

As ambitious as it is brutal, the ferocious fight scenes are rendered in a number of impressive styles; subjective camera positions, overcranked, sped up, slo-mo, geysers of blood, inspired and unnerving sound design, all at a dizzying and dynamic pace.

Sure, the misogyny, misplaced aggression, self-loathing, and crass vulgarity can be grating, but it also frequently reaches a sublime place of penance and braggadocio (the fight choreography combined with De Niro’s full commitment to the role is nothing short of a miracle) that is pure Scorese (Michael Chapman’s expert lensing and Thelma Schoonmaker’s editing expertise are also at their respective best).

9. The Seventh Seal (1957)

A profound and philosophical classic of world cinema that unravels in Sweden during the Black Death, Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal is a masterclass in iconography, artistic vision, and the silence of God. Max von Sydow is unforgettable as Sir Antonius Block, a knight who has returned from the bloody Crusades only to find that his homeland is in the throes of an apocalyptic plague. Challenging Death (Bengt Ekerot) to a chess match for his life, and tested and tormented over his new found belief that God doesn’t exist, how long can he evade Death and will he find redemption before it’s too late?

The New York Times scribe Bosley Crowther detailed how Bergman’s themes were enhanced by Gunnar Fischer’s sterling cinematography: “the profundities of the ideas are lightened and made flexible by glowing pictorial presentation of action that is interesting and strong. Bergman uses his camera and actors for sharp, realistic effects.”

Tackling themes of great heft such as man’s mortality, spirituality, religion, and reflections therein, The Seventh Seal had a stunning visual symbolism that, as James Monaco describes it in his book “How To Read a Film” as being “immediately apprehensible to people trained in literary culture who were just beginning to discover the ‘art’ of film, and it quickly became a staple of high school and college literature courses… Unlike Hollywood ‘movies,’ [The Seventh Seal was] clearly aware of elite artistic culture and thus was readily appreciated by intellectual audiences.”

While it may not be the best film in Bergman’s astonishing oeuvre, it is perhaps his most recognizable, and ironically perhaps his most long lived. Don’t miss it.