8. The City of Lost Children (1995, Marc Caro and Jean-Pierre Jeunet)

Jean-Pierre Jeunet has been quietly making distinctive, singular movies that buck against traditional storytelling for many years (he also made Alien Resurrection, but the less said about that, the better). He is most famous for Amelie, essentially a romantic comedy and one of the most beloved of French films, but it is in the genre of science fiction that he made his mark in the 1990s, with Delicatessen and City of Lost Children.

The latter is the tale of a futuristic scientist who kidnaps children and steals their dreams. It is, in essence, a cyber-punk Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, an elaborate fairy tale, the kind of film Tim Burton may have made in the early 1990s.

It is its extraordinary visual style, rather than its storytelling, that sets The City of Lost Children apart; as a visual experience, it is unparalleled. The images of the scientist’s twisted creations (including a brain-like entity that exists in a fish tank), the strange electric universe that the scientist inhabits, and the sheer grotesquerie on show all make this beautiful, if distressing, viewing.

Fun fact: there was PS1 game made of City of Lost Children in which you play the main protagonist, a young girl. It echoes many of the scenes of the film, and plays as a kind of ‘point-and-click’ adventure.

7. Koyaanisqatsi (1982, Godfrey Reggio)

At the risk of spouting clichés, Koyaanisqatsi is less a film than a journey. It has no plot, no characters, no dialogue. It is, instead, a series of glorious and worrying images of our earth, transmogrified and metamorphosed into something unrecognizable, something seen through a visitor’s eyes, or through the eyes of some deity, standing high and aloof.

In the Native American Hopi language, “Koyanaanis” means turmoil and “qatsi” means life. The film’s subtitle is ‘Life out of balance’. Godfrey Reggio, the director, intended the film to be an environmental statement, a testominal of our earth and humanity’s essential separation from nature. It is like a reverse time-lapse of Genesis, portraying the vast sanctity of nature slowly imbued and poisoned with human interference and involvement.

After the elemental beginnings, our strange and distant civilisation is depicted in all its intentional isolation from nature. And throughout it all is Phillip Glass’ hypnotic ambient soundtrack, less music than the sounds of our creation and eventual destruction, as filtered through the vast subconscious of the human race.

Reggio followed the film with Powaqqatsi (Life in Transformation) and Naqoyqatsi (Life as War) to complete one of the most startling trilogies in all of film.

6. Sweet Movie (1975, Dusan Makavejev)

The title is at once wholly ironic, and enormously literal. Sweet Movie is as debased and morally soiled as they come. A beauty queen and a ship’s captain occupy their time through child killing, coprophagia and ritual murder, much of it while glazed and smeared in syrup, treacle or other confectionary (hence the title).

Like Mysteries of the Organism (see above), however, Sweet Movie isn’t an exercise in pointless immorality. Much like Pasolini’s cited intention with Salo, Makavejev is indicting authoritarianism of all kinds, as well as satirising movie-making in general.

The violence of the 20th century ensured that human life, in certain parts of the globe, was worth nothing; Makavejev depicts the human body, the very thing that had become disposable in his own country, in all its functional glory. That this is so shocking illustrates why von Trier’s The Idiots is so outrageous: it confronts us with human behaviour and imagery that is nonetheless true.

5. Black Moon (1975, Louis Malle)

One of the auteurs of the French New Wave, Louis Malle was a prolific and diverse filmmaker. He is rarely mentioned in the same breath as Godard or Truffaut, but his output was immensely varied and interesting.

Black Moon is a true forgotten avant-garde curio from the 1970s, proof that it was a time of sheer experimentalism, when even great filmmakers could fund their wildest flights of fancy. Malle never shied away from controversial subject matter, and Black Moon is an overt comment on gender and sexuality. It exists in the realm of dreams, and attempts to pay homage to the great surrealist films of the 1930s.

Malle himself has said that the film is a homage to Alice in Wonderland; the plot, such as it is, mimics Carroll’s novel considerably, concerning a woman who seeks to escape to a quiet country house from an apocalyptic war between the sexes. Here she is confronted by a series of increasingly bizarre and ethereal happenings, and eventually breast-feeds a unicorn.

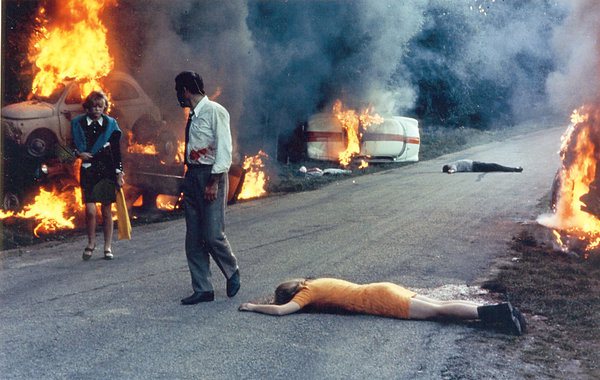

4. Weekend (1967, Jean Luc Godard)

Godard’s run of films during the 1960s is a competitor for the single greatest cinematic achievement by any one person. From Breathless to Weekend, every film is a distinctive, stand-alone masterpiece, chronicling the nature of art, the artist, creativity and anti-conventionalism. Weekend is his final, woolliest film from this most creative period.

Like many of the films on this list, it is about the collapse of ordinary society into a kind of primordial existence, and a savage indictment of bourgeois sensibilities. Many have called it a document of revolution, which in 1967 seemed a distinct possibility; this anarchism extends beyond society and politics, and encompasses cinema itself, which Godard declares ‘dead and buried’ the end of the film.

Indeed, this is the film that called an end Godard’s attempts at ‘storytelling’; following 1967, he would turn to more experimental documentary-making and attempt to critique the vast history of filmmaking in his seminal Histoire du cinema. As such, it is easy to see the culmination of a life’s work in Weekend; it certainly embodies and distils the 13 films that came before into a statement of closure and finality. It also contains the world’s finest traffic jam scene.

3. L’age D’or (1930, Luis Bunuel)

The earliest film on this list, directed by the legendary Luis Bunuel, L’Age D’or offended almost everybody it is possible to offend on release, and was banned in several countries. Bunuel had a history of being excommunicated and made films in many different countries, managing to upset governments across the world.

L’Age D’or is his first full-length attempt at surrealist cinema, coming only a year after his breakthrough masterpiece, Un Chien Andelou, which broke ground for depicting the language of dreams and the subconscious mind. He wrote and created the film with Salvador Dali, though they came to hate each other throughout the course of filming.

Bunuel was obsessed with societal sexual habits, false religiosity and the middle class, and L’Age D’or skewers all three in brutal fashion. A couple attempt to consummate their love, but are consistently thwarted by the Catholic Church, clucking housewives and disapproving family members.

A woman enthusiastically fellates the toe of a religious statue. A man excites his lover through acts of severe physical cruelty. A crucifix is adorned with the scalps of recently murdered women as a grinning bishop looks on. Many of the films on this list owe an immediate debt to Bunuel and L’Age D’Or.

2. Inland Empire (2007, David Lynch)

Where would a list of weird movies be without the high priest of American weirdness? Lynch’s movies are dreamscapes, in which the world of fairy-tales become twisted and broken. Lynch understands the visions of apparent bliss that humans have erected around themselves, and throughout his career sought to deconstruct these illusions in vicious fashion. From Blue Velvet to Mullholand Drive, his great theme is the darkness that lies beneath the façade of everyday civilisation.

Inland Empire is his last full-length movie (after this, major studios refuse to finance any of his projects) and also his most ‘Lynchian’, in that it recreates the terrors of a lucid nightmare and mass psychosis. It concerns the mental decay of young actress, who suddenly comes to believe that she is the character she is portraying in movie (or perhaps a series of characters) and delves into a dark, symbolic world of crumbling identity and human-like rabbits.

There is one thing that elevates Inland Empire above the rest of Lynch’s works, all of which could have appeared on this list: it is shot completely on grainy digital video, giving it a grainy, VHS quality. This gives the film a truly claustrophobic quality, quite unlike anything ever put to film before. Inland Empire has the power mesmerise and disturb in almost Biblical magnitude.

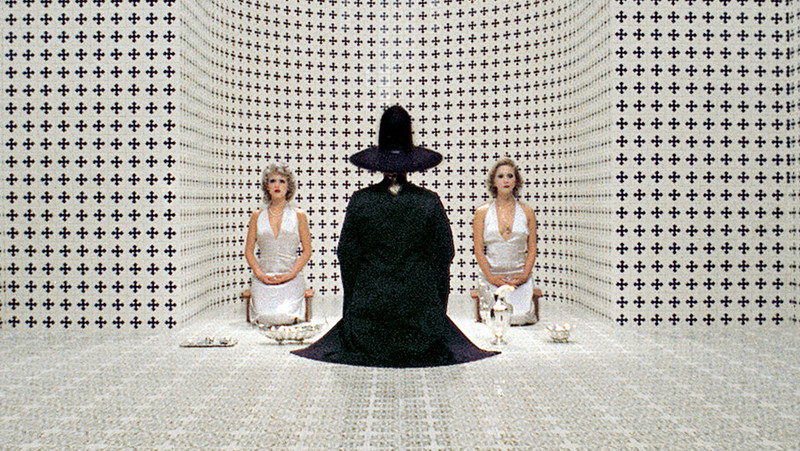

1. The Holy Mountain (1973, Alejandro Jodorowsky)

In the first ten minutes of The Holy Mountain, the holy grail (ahem!) of ‘midnight movies’, Jodorowsky deals with Christ, the Bible, Christianity and religious symbolism in a whirlwind of exceptional blasphemy. Some of the imagery from these ten minutes would render The Holy Mountain deserving of a place on the list alone. But the film continues. For almost 80 minutes, never letting up. It was not a movie made to watch with your parents. Or anybody, for that matter.

The Holy Mountain is, predominantly, a comedy, an indictment of our society and a dream of something otherwordly. Jodorowsky was a spiritual wanderer; his movies are a mish-mash of the pseudo-religious sensibilities that became prevalent during the 60s and 70s, just as midnight movies gained an enormous subterranean cult following and the countercultural revolution was in full flower.

Both this and El Topo are strange allegories of kabbalistic awakening, journeys of symbolism that are either infinitely profound or nonsensical, depending on your willingness to surrender to them. They are films must be seen to be believed. A single example: a man attempts to drown a gaping-mouthed religious convert using only his own breast milk, until his breasts turn into the heads of snarling tigers, and both cry out in a kind of spiritual ecstasy.

Author Bio: Daniel Pryce is a a film devourer and father of two. He writes about the films he loves. And some of that suck.