5. Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me

The revival of “Twin Peaks” has been a blessing for the fans. We never thought we’d get another season. We thought it would end with Cooper being lost in the Black Lodge forever – which might have happened again at the end of season three, anyway, but let’s not get into that. There were so many treasured moments in the third season and perhaps one of its greatest moments involved the return of Carl Rodd, a supporting character in “Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me”, a prequel film of the show.

I would certainly recommend you watch season three after “Fire Walk With Me” as it has the perfect continuation to the Carl Rodd character. However, if we never got a season three, his appearance in “Fire Walk With Me” would be in no way diminished. Carl is the owner of a trailer park who gets questioned by the FBI since a girl who lived in one of his trailers was found murdered. In the film he just seems like a crank, but there’s so much more to his character.

While being questioned, an old hunchbacked lady mistakenly enters his trailer. There is a sudden sadness in his eyes. We aren’t sure if he knows this woman, but we know what she represents to him. Seeing this frail and confused old woman reminds him of death, the nothingness that is awaiting him. ”You see, I’ve already gone places,” he says to the FBI agent, nearly ready to break down. ”I just want to stay where I am.”

Stanton pulls of this sudden sensitive turn magnificently. Suddenly he’s this man that is confronted with his own mortality, a man who knows it’s near. It’s a short but haunting performance. In the third season he returns as a 90-year-old man. He’s more relaxed, enjoying the little moments in life. He has seemingly accepted the concept of death after all this time.

In one his best scenes he’s sitting on a park bench, enjoying his cigarette and looking up into the sky. He is distracted by a mother playing with her son, and this sight of pure innocence makes him smile. But he is quickly reminded of how quickly and brutally, life can be taken away as the boy is killed in a hit-and-run accident. Carl runs to the scene and he witnesses the life force of the boy leaving his body. Under the accompaniment of Angelo Badalamenti’s beautiful score, he comforts the mother. It’s one of the most memorable moments in the “Twin Peaks” saga and it’s all thanks to Stanton’s indelible presence.

And he also sings in the show too. Sometimes we are indeed lucky in this life.

4. Repo Man

There’s a short documentary on the collector’s edition of “Repo Man” called “Harry Zen Stanton” which is just a 20 minute or so interview with Stanton about his philosophy of life. Admittedly, it’s a rather awkward interview at times. Stanton seems uncomfortable with the eager questions of the interviewer. You can see him frequently looking away from him as if he’s looking for an exit.

Nevertheless, we do get an understanding of his philosophy. He boldly exclaims that there’s nothing wrong with nihilism, that nothing is ‘really’ important and that consciousness is merely playing a game with us. He’s just playing the game. But if you think he’s going to get all spacey, don’t worry. He quickly denounces being the wise old father, which would be a practice of the ego. This Buddhist philosophy would explain his lack of pretentiousness. We are who we are. Things are going to be how they are. Follow your path and accept the journey. Sing a song along the way.

It’s completely different from his character in the bonkers film “Repo Man”, directed by an equally bonkers Alex Cox. In it he plays Bud, a repo man who takes a young punk under his wing. He mentors the punk into the mad world of vehicular repossession, telling him about the ‘Repo Code’ and introducing him to a series of oddball characters.

Stanton is frequently hilarious in the role of the speed-snorting, gritty repo man. But he manages to imbue a sense of tragedy as well. Despite his grand monologues about the ‘Repo Code’ and how ordinary people suck, there is a hidden hypocrisy. He’s a prisoner of the American Dream, just like everyone else. He wants the same things: enough money to relax. He doesn’t want to drive around at night, being confronted by massive poverty, dealing with low-life punks and getting shot at. After being wounded in a shoot-out, he becomes desperate. He breaks his own code, possibly losing his life because of it.

Stanton replaced the original choice of Dennis Hopper – who’s up there with Stanton. Hopper would have been great in the part, but Stanton made it his own. Hopper might have had the madness but Stanton had the grit and humility. Budd would have been an enjoyable madman if Hopper played him, but Stanton made him seem like a real person. Stanton frequently butted heads with the director, losing his cool at one time, telling Cox: ”I’ve worked with the greatest directors of all time! You Know why they are great? Because they let me do whatever the fuck I wanted!”

“Repo Man” shows that Stanton had great comedic timing, which he would use frequently in his career. The film would eventually become a cult classic and it’s hard picturing this happening without Stanton’s unforgettable turn.

3. The Straight Story

In “Partly Fiction”, David Lynch talks about how Stanton as a performer possesses that really rare ‘innocence and naturalness’. It’s what he does between the lines; while you can see other actors thinking about their next line, Stanton makes his delivery seem phenomenally real.

Lynch and Stanton have worked together on numerous projects, from shorts to full-length features, in his “Twin Peaks” revival show, and soon we will see Lynch co-star next to Stanton in “Lucky”. Lynch attributed Stanton’s greatest abilities, from his sad-sack innocence in “Wild at Heart” to his subtle menace in “Inland Empire”, to his ability to say so much in silence with “The Straight Story”. It’s not hard to see why Stanton considers this to be his best team-up with Lynch.

Stanton only appears in the final few minutes of the film, but his acting, alongside Richard Farnsworth (another performer who is greatly missed), is some of the most touchingly beautiful of his career. Perhaps the monologue in “Paris, Texas” would always be his best, but this one comes neatly close. His ability to make his character come alive in so few minutes with so little dialog is something most actors wish to aspire to, and most of them just can’t do it as well as Stanton.

Stanton is the emotional climax of the film, with Farnsworth playing Alvin, a farmer who travels a long distance in rural Americana to reunite with his estranged brother Lyle (Stanton). From the moment they see each other, you can see the connection between them in their eyes.

There are so many unspoken words. ”Did you ride that thing all the way out here to see me?” asked Lyle, realizing the trouble Alvin went through to see him. We can see that he’s trying to hold back the tears. ”I did, Lyle,” Alvin says. Both of them are nearly bursting into tears. Lyle looks at Alvin, Alvin looks back at them, and in their eyes you can see their history, you can see pain and ultimately forgiveness.

They are so happy to see each other before it was too late. Alvin follows Lyle’s gaze as he looks up into the sky. The camera follows their gaze all the way up to space. This was just a small and seemingly insignificant moment in the great cosmic scheme of things. But for these two insignificant humans, this moment meant everything to them.

2. Paris, Texas

Sometimes there’s the perfect fusion of talents, which culminates in movies such as “Paris, Texas”. You have the visual eye of Wim Wenders, the literary drama of Sam Shepard, the sombre music of Ry Cooder, and finally, an intimate performance by Harry Dean Stanton. This would be his first leading role after working as an actor for more than 30 years. At first Stanton was nervous being a leading man, but he would ultimately consider this the high point of his acting career. He stated that if this would have been his last movie, he would have been satisfied.

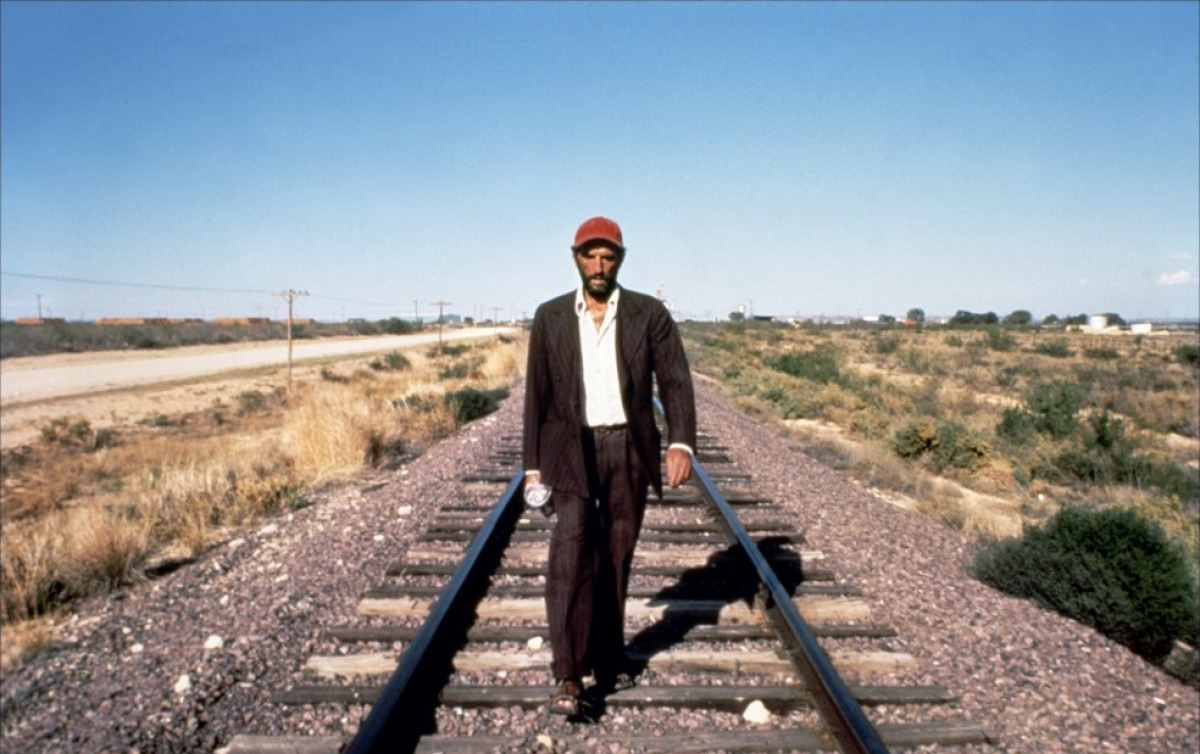

It opens with Travis Henderson (Stanton), bearded in a disheveled suit and red cap, wandering the desert. When he collapses in a local bar, a doctor tends to him. For the first 30 minutes of the film, Stanton doesn’t say a word. There’s something stopping him from talking. The doctor calls up his brother (Dean Stockwell) who travels a long way from his comfortable suburban home to pick him up.

It turns out that Travis has been missing for four years; we don’t know why and Travis doesn’t seem to remember. His brother has been raising Travis’ son in all this time. We can gather that something painful must have happened that made this man flee toward nowhere. Slowly Travis begins to piece together his history and together with his son, he seeks to mend the past.

The true mystery of his disappearance is heartbreaking but not in the conventional Hollywood sense. There was no tragic death that caused his disconnection – it was because of his own doing. There was no sudden happening, he himself is to blame. He ran away because he couldn’t face himself. He couldn’t accept the abuse he inflicted on his lover and child. He imagined blue flames burning his sheets and he had to run away, run away until the sun went down. When the sun went down he ran away again.

This reveal comes in cinema’s most heartfelt monologue and the finest in Stanton’s career. In the end, there is redemption, though it still would mean loneliness for him. He watches from a distance as a child is reunited with his mother and leaves them, driving into the night. They wanted him in their lives but he couldn’t let it happen.

So he continues to do what he has done in the last four years and will probably do for the rest of his life: he runs. He runs into the night, toward that vast deep country where nobody knows him, somewhere where there is no language or streets. Perhaps it’s an act of heroism. He knows that the more he becomes his former self, the more his demons will start to come back and hurt the ones he loves.

The ending was something Stanton himself had issues with. Even though he probably knew that it was the best possible ending, he still hoped that Travis could find happiness again. He gave everything for this role. He went into his own private history, perhaps explored his own alienation from his parents in order to do the part justice. This is mentioned briefly in “Partly Fiction”, the final entry on this list.

1. Harry Dean Stanton: Partly Fiction

If you really want to know who Harry Dean Stanton was, this documentary is probably the closest you’ll ever get, but some parts will always remain a mystery. If you want to know about his home life, this documentary won’t reveal much. His eyes drift to a painful past when the subject of his childhood is mentioned. He doesn’t want to talk about it. We know it wasn’t pretty. Some things will always hurt.

If you’re a fan of his acting or of his singing this is however a must see. He frequently breaks into song. When he sings Harry Nilsson’s “Everybody’s Talkin’”, he closes his eyes, reaching into that deep place inside of him to deliver his earnest singing voice. When he opens his eyes after finishing the song, his eyes are moist.

There are clips of his greatest performances. Some of his closest celebrity friends are interviewed. Sam Shepard tells us why Stanton was the perfect person to play Travis Henderson. Wim Wenders tells us how Stanton was insecure about playing a leading role. Wenders also tells us how about Stanton used his own his life story to get inside the Travis character. Deborah Harry talks about writing a romantic song for Stanton. Kris Kristofferson talks about the drastic measures Stanton used to scare Kris properly in preparation for a scene.

Stanton talks about his admiration for Marlon Brando, how close they were in the last moments of Brando’s life. Living with Jack Nicholson in the late 60s, their close friendship. In his living room we see beautiful framed pictures of his incredible life. He talks being heartbroken over Rebecca De Mornay leaving him for Tom Cruise. We see Stanton drinking among barflies, lying to one of them about who he is (”I’m Ron… I’m doing a space program”). The bartender, who reveals that he knew him for more than 40 years, says it best when he tells Stanton: ”You don’t talk much but when you say something, you mean something.”

There is beautiful black/white photography in the film; it captures the sad eyes of Stanton perfectly. In the backseat of his car, while driving deep into the night, Stanton talks about the comic nature of things, how all of us chase this freedom of the fear of death, the void that’s coming our way. ”It’s all gonna go away. You gonna go away, I’m gonna go away, everybody’s gonna go away. The sun is burning out. Earth’s gonna go away. It’s all transient. Everything is transient so it’s ultimately not important. It’s all fleeting, passing and that’s not a negative concept, it’s just what it is. It’s liberating.”

It is what it is. We will miss you Harry.