The history of film is the history of mankind from 1895 to the present day. Cinema has documented everything from the palpable and the general (conflicts, geo-political changes, significant events, remarkable destinies) to the impalpable and the intimate (thinking movements, behavioral adjustments, deaths, rebirths and emergences of values).

More deeply than finance, more covertly than artistry, it is ideology that was, is and will always be the backbone of cinema. Therefore, it is only natural that films would form an extraordinarily accurate map of the changes that occurred in their makers’ and their audiences’ mentalities.

The 20th century has been a period of intense questioning, during which practical philosophies have dislodged one another with stunning rapidity. Here are ten films that illustrate how greatly morals have shifted during this brief lapse of time that is called contemporary period.

There are spoilers in this list!

1. Birth of a Nation (1915) – dir. D.W. Griffith

“Birth of a Nation” is the film that automatically springs to mind (at least in the western cultural sphere) when denouncing malevolent ideologies in cinema. Much like Leni Riefenstahl’s “The Triumph of the Will” – which is less familiar to the general public – Griffith’s film and its depiction of The Afro-American population attract strong criticism to this day due to what seems to be a paradoxical reason: its artistic merit.

But it is undeniable that, if Griffith’s work would not have been a cornerstone of world cinema, perfecting techniques like parallel editing, reinforcing the classical narrative style that would become the undisputed norm until the emergence of the New Waves of the fifties and sixties and creating a mold for almost all war films to follow, its racist discourse would have been consigned to the dustbin of history.

The film created a stir when it was released, becoming the United States’ highest-grossing film until the release of “Gone with the Wind” (1939), reviving the Ku-Klux-Klan as well as eliciting the outrage of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Nowadays, however, the indignation is prevailing and there is hardly any mention of the innovatory nature of “Birth of a Nation” that is not accompanied by an indictment of its core principles.

2. The Sheik (1921) – dir. George Melfold

“The Sheik”, an adaptation of a polemical but widely popular novel by Edith Maude Hull, was intended as a vehicle for the charisma of Rudolf Valentino, the Italian-born actor that would later become eponymous with the Mediterranean model of masculinity.

The film was unapologetically targeting a female audience and it would take the crystallization of feminist claims and of critical gender consciousness for voices to rise against the narrative arch of the protagonist, a young Englishwoman who falls in love with her abductor, an Arab tribal chief.

But except the belittling of abuse against women and the patriarchal conclusion (Lady Diana, who sought to conserve her independence by refusing to marry, is finally brought to reason after a traumatic experience), there are other issues that perturb contemporary commentators. One which is notable due to its pervasion in other films of the period is the fear of miscegenation. This most strongly surfaces in the slightly comical final revelation regarding Sheik Ahmed’s real origins.

More gravely though, the film capitalizes on the angst of the American society as a whole that could never fully reconcile with its essentially cosmopolitan nature, and is therefore not the harmless entertainment it seems at first glance.

3. Kvarnen (1921) – dir. John W. Brunius

This relatively obscure film is representative of a current that manifested itself during the Golden Age of Swedish silent cinema. While not being aesthetically homogenous, films like “Kraven”, “Grevarna på Svansta” (Sigurd Wallén, 1924) or “Folket i Simlångsdalen” (Theodor Berthels, 1924) used the tattare (travelers or Romani people) as dramatic elements.

They divided into two categories according to the nature of the stereotypes that they spread: the ones that portrayed female tattare as demonic, shrewd beings with an unrestrained sexuality and the ones whose narratives consisted of the chase and the ultimate punishment of the brutish male tattare, usually the rapist of a Swedish girl.

More enlightening than the films themselves regarding the mentalities of the time are the reviews that, in the case of “Kvarnen” for example, were unanimous. The actress Klara Kjellblad, who plays the female tattare, was praised relentlessly for the intensity of her performance.

A single voice was discordant, but for all the wrong reasons: critic Tora Garm’s who wrote, according to Tommy Gustafsson’s article “Travelers as a Threat in Swedish Film in the 1920’s”: “She has all the external requirements, strikingly dark and with a healthy, ample bodily constitution. Nevertheless, […] she completely shines with cleanliness despite the fact that she does descend from a filthy ramshackle where she feels at home”.

4. Der Ewige Jude (1940) – dir. Fritz Hippler

Many scholars have tried to define the essence of cinema, oscillating between the two dominant aspects of the medium, the artistic and the economic. Despite numerous attempts coming from theoreticians as well as players in the industry to make one of the aspects prevail over the other, critic André Bazin’s seminal question “Qu’est ce que le cinema?” (What is cinema?) still lingers.

However, Hitler and his ministry of propaganda Joseph Goebbels proved to be astute observers and practitioners of cinema, as they perceived how the foremost effects of films on any type of audiences (eliciting emotional responses and forging opinions) could be bent to serve their purposes.

Among the propaganda films whose role was spreading anti-Semitic sentiments amid the population, “Jud Süß” (Veit Harlan, 1940) best illustrated Goebbels’ method of concealing the ideological content behind high production values, engaging storylines and a distancing historical context, that only alluded to the then-existing situation.

On the other hand, Hitler’s more unsubtle approach is perfectly illustrated by “Der Ewige Jude”. Upon release, the film was presented as a documentary, but it is now known that most scenes where staged in order to support the claims the Nazis advanced about the Jewish people.

While this was common practice in documentary-making before the rise of cinéma-vérité (Robert Flaherty’s “Nanook of the North” being an illustrious example), treachery was never more abhorrent that in the case of “Der Ewige Jude”. It paved the road to the habit of perpetually questioning images in spite of Godard’s poetic formula that cinema is “truth twenty-four times per second”.

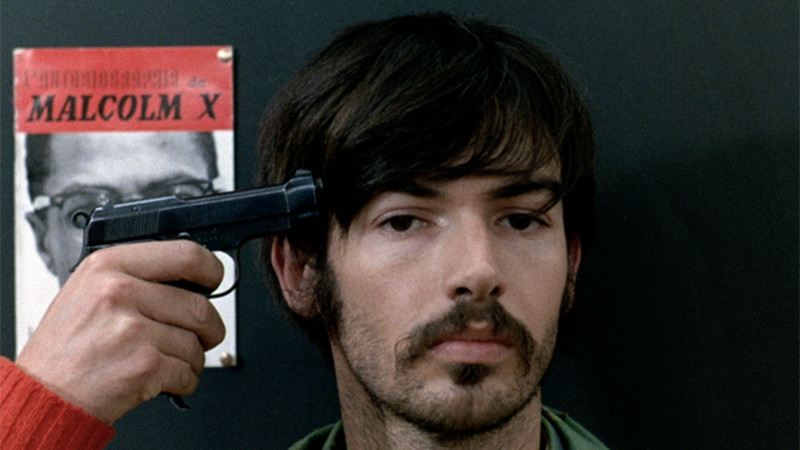

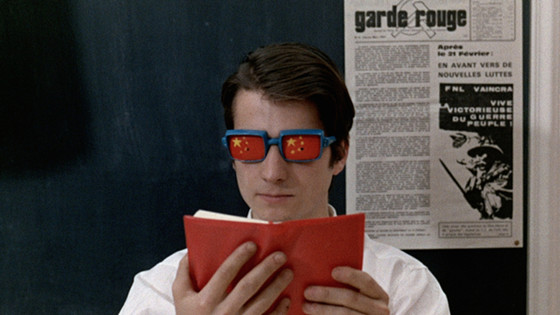

5. La Chinoise (1967) – dir. Jean-Luc Godard

In 1967, Jean-Luc Godard was approaching maturity as well as iconification as a leading figure of the cinematic avant-garde, and he wanted to escape both these states. His encounter with Anne Wiazemsky was more than an encounter with a woman who was to become his wife and his muse during his Dziga Vertov days, it was an encounter with a fringe of youth that the 20 year-old girl encapsulated.

Wiazemsky was a student at the University of Nanterre, which would be the epicenter of the tumult of May 1968, which meant that she was assisting to the clan wars between leftist factions and to the incessant circulation of ideas that aimed to renew the blood of French society.

Despite the fact that Wiazemsky was involved with anarchist circles, Godard was more interested in Maoism, an ideology to which he would eventually whole-heartedly adhere. “La Chinoise” therefore discusses the necessity of revolution, the morality of political assassination, the aftermath of violent actions and ultimately the limits of political engagement.

Legend has it that during the protagonist Véronique’ s clash with philosopher Francis Jeanson concerning the Maoist cell’s plan to execute a Soviet diplomat, Godard whispered in Wiazemsky’s earpiece his own answers to refute Jeanson’s pacifist arguments.

If the film-maker’s narrative and aesthetic devices have become indispensable parts of post-modern cinematic technique, the atrocities committed under Mao’s rule and more generally the failure of communism around the world have greatly discredited his political stance.