As you will know, the medium of cinema can often stir quite the debate. Audiences analyse and enjoy films in different ways, so it comes as no surprise that two people can watch a film together and feel completely oppositional feelings towards it. Yet, this doesn’t have to be seen as a negative thing.

Often, the best films to discuss in detail are the films that serve to divide audiences, and this can be for a number of reasons. Those who love it will argue its case, and those who disagree will take pride in explaining to them exactly why they are wrong on this one, or maybe your own opinion isn’t entirely made up just yet.

There is nothing worse than when film fans are blinded or unable to take on board an opinion of another; opinions should be considered, and debated, but never entirely dismissed. These are a selection of divisive films which – whether you adore or despise them – are actually really enjoyable to consider and discuss. With only one exception, all of these films are well-known and have caused conflict between film fans, critics, or both in some capacity, and are all worthy of reflection.

10. Signs (M. Night Shyamalan, 2002)

It seems fitting to begin with a filmmaker who has made more than his fair share of divisive cinema. There were numerous films that could have been included, notably his 2004 effort The Village, or his found-footage attempt The Visit. Even The Happening, which the majority agree was a colossal disappointment, is bafflingly admired by some as an ironic b-movie of sorts.

It is more fitting, however, to include the film that began Shyamalan’s descent into segregating audience opinion. The Sixth Sense and Unbreakable brought the Philadelphia-raised director great acclaim, even resulting in him being heralded as “The Next Spielberg” by TIME Magazine in the advent of Signs, which funnily enough triggered his departure from affirming such a title.

Some actually consider it to be his best film, while others denounce this venture into science-fiction as being the moment they lost interest in a once promising filmmaker. Despite the director resurrecting his career more recently with the vastly overrated Split, the debate around Signs still continues.

The narrative revolves around a family whose farm is suddenly disrupted by gigantic crop circles. They discover that their property is not the only one to feature this mysterious system of communication, as the public begin to believe that extraterrestrial life may be in preparation to conquer Earth.

It’s a family-drama with science-fiction and horror elements, dealing with themes of faith, paranoia, and loss while simultaneously offering audiences a sinister tale of potential invasion.

The film boasts some truly terrifying scenes, and those who dislike the film often admit that, and that’s because the problem for most is introduced in the final act. Shyamalan has become famous, and later infamous, for his twist endings, and many take issue with the one featured in Signs.

It has been described as preposterous, illogical, and downright laughable by many viewers, who claim that it ruined what may have otherwise been a great work of science-fiction. However, there are many fans who defend the ending, reinforcing the aliens’ sheer desperation and urgency. Some have even introduced a fan theory that the creatures they encounter are actually demons.

Whatever your opinion may be, the last act of Signs has continued to be argued and discussed by the masses, and that is because there are so many possibilities and angles to take. Even discussing ways that it blends the home-invasion sub-genre with others is an interesting talking point. After many years, the film maintains stimulating disputation, and with good reason.

9. Flowers (Phil Stevens, 2015)

The only obscure movie to feature on this list is Phil Stevens’ first directorial feature credit, Flowers. It’s a very little seen gem of extreme cinema, and with much of extreme cinema, opinion varies. Stevens’ film is a surreal and abstract horror film which features no dialogue, which is already a strong indication that this isn’t exactly for more casual audiences.

Another indication is that it was released for home distribution on the independent label Unearthed Films, which specialises in the more hard to swallow side of independent cinema. While many consider the label to release brainless and grotesque gore films, they do in fact release some interesting and experimental features every so often, and this is perhaps the most impressive example.

A woman wakes up in the crawl space underneath the home of the man who murdered her. She peers out, witnessing yet another victim being dragged into the house directly above. Deciding to escape, she begins to navigate within the walls of the home. Unfortunately, there is no saving her, she is already dead. Trapped within a twisted state of purgatory, the identity of the protagonist shifts between six female murder victims as they come to terms with what is happening to them, navigating a labyrinth of dark and disturbing confines.

Flowers is an intriguing film because it manages to be beautiful, devastating, and horrific all within a unique and original narrative. The imagery is unsettling and unforgettable up until the very last shot, of which attempts to the show the audience an ordinary location made terrifying by our own prior knowledge. Coming away from the film is almost like waking up from a nightmare, with its images lingering for days to come.

It is affecting, despite never being relatable, and that is because Stevens is presenting the aftermath of a serial killer in a way that emotionally resonates with those that can sympathise with the victims. While some viewers have clearly found themselves deeply engrossed in the film’s message of destruction and its repercussions, others have found the film to be an experimental exercise which uses arthouse ambiguity to disguise a sadistic love for gory and disturbing content.

The few that have seen the film harbour conflicting views, and the meaning and themes of the film can be debated for hours. The filmmaker doesn’t allow for easy answers, which make this such a great film for discussion; it’s simply a shame that more people haven’t seen it to allow for wider analysis.

Many will be turned off by the twisted content of Flowers, but equally, others will continue to find depth and poetry in this thought-provoking piece. For those who haven’t seen it, do, and weigh in on the debate for yourselves.

8. The Dark Knight Rises (Christopher Nolan, 2012)

It can be argued that Christopher Nolan’s concluding chapter to the beloved “Dark Knight” trilogy isn’t particularly divisive; it received praise from audiences and critics alike when it was released 2012, and contributed to one of the most heralded film series of all time.

However, since then, many have reconsidered that the film is not only the weakest of the trilogy, but that it isn’t as well-thought out as they had initially believed, now claiming that the hype and excitement for its release prematurely swept them into enjoying it a little too much, rather than considering it for the merits of its predecessor.

Bruce Wayne (Christian Bale) must become the caped crusader once again when the arrival of evil mercenary Bane (Tom Hardy) promises Gotham their most threatening foe yet. Nolan ultimately reinvented the superhero genre with this trilogy, and it’s arguable that the genre will never see anything with as much promise again.

In 2008, The Dark Knight took the world by storm, and four years later, fans found themselves flocking to go and see the final installment. Most loved it, and yet since then, the internet has seen an increase of audiences accusing the film of being Nolan’s weakest, taking aim at the film’s ending in particular and certain plot points that they deem idiotic.

Fans of the masked vigilante began to question a number of things: the final encounter with Alfred, the unexpected turnaround of the villain, the entrapment of Gotham’s police force, just to name a few. Perhaps most irritable for viewers, however, was the film’s final shot, departing with the announcement that a popular hero had been awakened despite knowing already that the trilogy would definitively end here.

This led to some exclaiming that the character development was a waste of time, along with emerging accusations of Nolan not knowing how to end the trilogy because of his decision to conclude on a frame that falsely suggests more to come. However, many champion the film, and it has even become many’s favourite of the trilogy, being held up as a tense and electrifying blockbuster.

It is particularly entertaining to have a conversation with a group of people who feel both positively and negatively about The Dark Knight Rises, as many are actually divided within themselves on how they truly feel about the film.

It is a debate that can last for hours because it is a monumental film of the twenty-first century, whether people love it or not, strong feelings towards it are inevitable. Nolan’s offering had to follow the most universally admired superhero film of all time, and to deliberate its success goes way beyond the criteria for any film of its kind.

7. Heaven’s Gate (Michael Cimino, 1980)

Michael Cimino’s epic western has a reputation unlike anything else in cinema. It single-handedly almost bankrupt United Artists after it quickly became a critical and commercial disaster. After the success of 1978’s The Deer Hunter, which won five Academy Awards, the studio allowed Cimino full creative control over his next project.

Embarking on the making of Heaven’s Gate with the initial budget of $7.5 million, it soon escalated into the territory of $40 million, which at the time was unheard of. It was reported that Cimino would often fire actors and destroy sets, intent on achieving his very detailed vision at any expense, quite tragically, extending to the expense of the safety of many animals on set.

After witnessing the graduation of James Averill (in a charismatic performance from Kris Kristofferson), a bright and illustrious future appears in his grasp in the year of 1870. Twenty years later, his world appears very different. He returned from Harvard and back to Wyoming, and in the present day, is a Marshall witnessing the cultural divisions of the county.

After reinforcement from the government, an elite group compile a death list of one-hundred and twenty-five names, employing mercenaries to murder them – however, this en masse assassination escalates into cruel and bloody war.

There are numerous cuts available of the film, with the final director’s cut capping in at two-hundred and sixteen minutes. It’s a lengthy engagement, and approaching a film like Heaven’s Gate requires patience and investment – if one is expecting a straightforward western, it would be wise to look elsewhere. Cimino’s film is ambitious in its scope; it aspires to explore romance, violence, politics, and when the film was released, this was the problem many had.

It was considered the juggling act of a filmmaker who in his attempts to perfect and achieve so much, ended up achieving very little. It never commits to one thing, and in aiming for everything – an epic in every sense of the word – many believed that it fell flat as a colossal and undisciplined mess.

Fortunately, decades later it was reevaluated by critics and audiences alike, with some hailing it as an American masterpiece, and it is even considered by certain critics as one of the greatest of all westerns. The narrative is timeless, and could even be translated into a modern day setting to comment on the state of the cultural divide in the US today – instead, it presents audiences with a recurring issue that has persisted throughout history.

Although it has received considerable praise later in its lifespan, it also continues to be bashed by film-fans as a bloated and indulgent carcass of a project. Debates as to whether Heaven’s Gate justifies it’s length, or whether it’s successful in the many genres it attempts, remains a heated talking point today.

With such a controversial and fascinating history, there is one thing that simply isn’t up for debate, and that is this: Cimino’s legendary western is still so exciting to dissect and discuss.

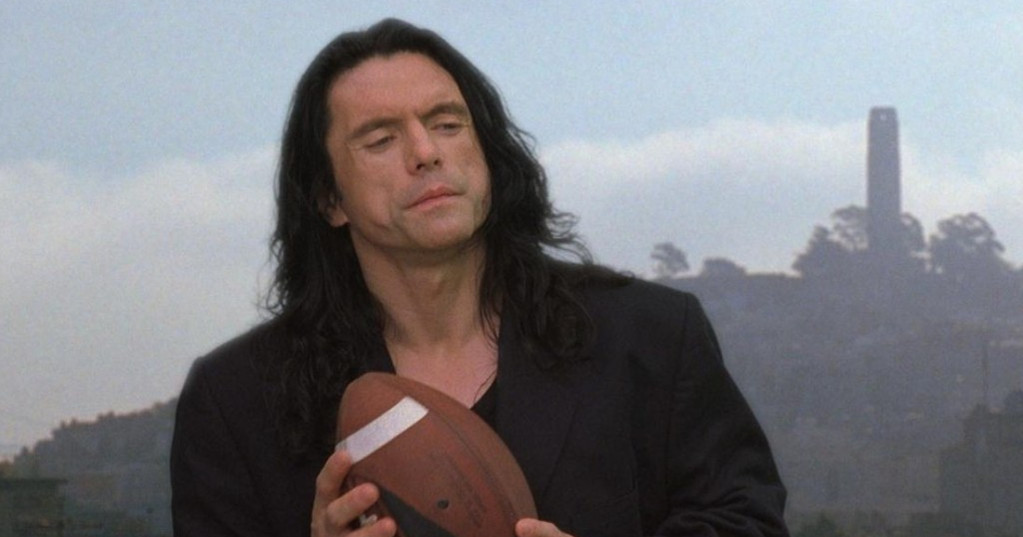

6. The Room (Tommy Wiseau, 2003)

Since James Franco decided to adapt Gregg Sestero’s book of the same name, cult-film The Room has received much more attention. Even before this, the film was perhaps the most significant cult hit since 1975’s The Rocky Horror Picture Show. Everything surrounding it, from information regarding its production history, marketing, legacy, is absolutely bizarre, and then there’s the film itself.

To outline the narrative is seemingly redundant. Johnny (Tommy Wiseau) is a successful banker whose “future wife” Lisa is cheating on him with his best friend Mark. The film is a series of poorly constructed conversations and tediously excruciating sex scenes, and yet, it became a phenomenon that has since burrowed its way into popular culture.

Many lines of dialogue have become catchphrases, and the image of Wiseau himself has become iconic – even many with a limited knowledge of the film burst into saying “Oh Hi Mark” because of his status as a meme. In this respect, Wiseau’s debut has become much more than a film, and has taken on a life of its own as one big joke that fans simply can’t get enough of. However, there is one thing that everyone is in agreement with: the film is terrible.

This modern midnight-movie classic has encouraged audiences to participate in a range of activities at regular public screenings; reciting lines and throwing spoons are commonplace at the home of The Room, The Prince Charles Cinema in London.

Audiences have a great deal of fun watching it together and interacting with the film and each other. It is quite a communal experience, so it is easy to see why many who refuse to get in on the joke simply regard it, without any enthusiasm, as the worst film ever made, because it truly is.

When it is mentioned, some will smile with glee, and others will roll their eyes in disgust. It’s incredibly entertaining to see those who clash in their opinions of Wiseau’s disasterpiece come together and discuss their opposing views, because both are usually well-informed and knowledgeable in their arguments. The Room is a mystery of cinema that will forever be debated as an enigmatic and puzzling experience.