5. Hour of the Wolf (1968)

Ingmar Bergman is one of the greatest film directors who has extensively focused on existential topics in their artwork. Perhaps he shares the king’s chair with Andrei Tarkovsky. Bergman’s all-time classics post various existential questions that will never wear out by time’s corrosion. Films like “Persona” and “Wild Strawberries” will always be shining stars in the sky of international cinema. But the legendary Swedish director has created endless treasures for us.

He calls it “the hour of the wolf.” It’s the hour of the night, when the sleep is deeper, the nightmares are more vivid, and thus, the subconscious more active than ever. In his homonym film, Bergman illuminates the murky mental universe of a reclusive artist, whose traumas, unfulfilled desires, and obsessive fears commingle, extruding him to madness.

Johan Borg is a painter. Defined by an artist’s internality and complex psychological profile, he has chosen an isolated lifestyle with his wife on a remote island that hosts only a baron’s family. In this mysterious place, chilling figures appear and disappear. The bourgeois neighbors persistently interfere in Johan’s personal life and challenge his inner oppressed forces. Figures from his past emerge, being embedded in his thoughts. What is real? What is fantasy? What is memory? Until the end, it’s never clear.

This is a Bergman’s lesser-known work. However, it really is a remarkable motion picture on many levels. The psychological horror portrayed on Max von Sydow’s terrifyingly aloof character represents the delicate separating wire between the troublesome artistic spirituality and madness.

What place should occupy such a soul? Where could a volatile artistic mind claim some peace and be discharged from its longstanding yearnings? In its horrifying yet beautiful demonized environment, “Hour of the Wolf” carves a mind’s deepest layers.

4. My Dinner with Andre (1981)

Have you ever caught yourself being carried away by a very interesting evolving dialogue in a restaurant or coffee shop? I guess that everyone would enjoy overhearing Wallace Shawn’s dialogue with Andre Gregory, as it takes place in Louis Malle’s film “My Dinner with Andre.” Based on a real dialogue of the two artists, this dinner encloses a totalitarian theory of life and the entire spectrum of its qualities.

Walking in the well-known and well-loved streets of New York City, Wallace is telling us that he’s obliged to have a dinner with an old friend whom he has been avoiding for ages. He introduces Andre as a weird personality. The two men meet in a fancy restaurant, but neither of them seems to be defined by the sparkly appearance of an artist, as most of us would consider it. Wallace has the looks of an ordinary man. He could have just been dismissed by his bureaucratic job. Andre, on the other hand, looks weak, exhausted, and lost.

Since the beginning of their conversation, a river of unusual experiences, ideas, and perspectives toward life flows unstoppably, stirring up a lot of queries over the gift of existence. Andre searched for the meaning of life in his trips, connections with humanity, and primal explorations of nature.

On the contrary, Wallace claims that life’s beauty lies in simplicity: in the delight of everyday coffee, in a restful night with a good companion, and in the sudden artistic impulse. Whichever side you embrace, this film provides plenty of food for thought.

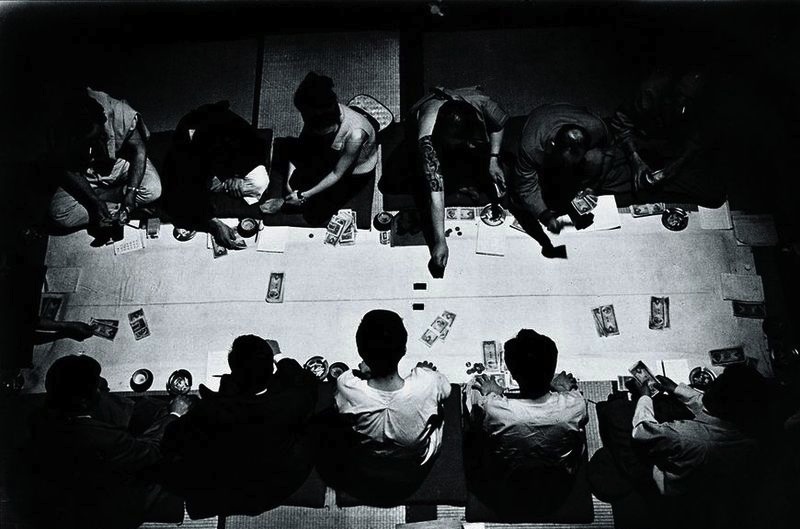

3. Pale Flower (1964)

A man is released from prison. He is an unhesitant outlaw: a mobster, a gangster, a killer. Prison was a gap in his life, but during his first rebounding day, the world seems miserable to his eyes. Observing the passengers in the crowded streets, he discerns the dull figures, the mechanic ways of walking, and the countless empty eyes. And then, promptly and automatically, Muraki comes back to his self-destructive and demanding life.

After his imprisonment, a woman still loves him and a gang awaits him. His woman is just like every woman. His gang is just like every gang. He’s still just Muraki, and life goes on. At a gambling club’s territories he meets a woman of another kind: she’s silent, with bright eyes and decisive attitude. She’s the story’s Pale Flower. Like Bonnie and Clyde, Muraki and his fragile pale flower move on together, on the chosen path of devastating self-exploration and self-denial.

Muraki and Saeko share the same blind passion for that overpowering feeling of the adrenaline flow in the blood. They are both obsessed with the constructed moments that emit a sense of life’s dominion over death. The problem is that on this rough road, these lost humans forgot to live. Eventually, Muraki returns to prison and learns that Saeko is dead. Pondering her death, he admits to his own self that even if she’s dead, he still desires her.

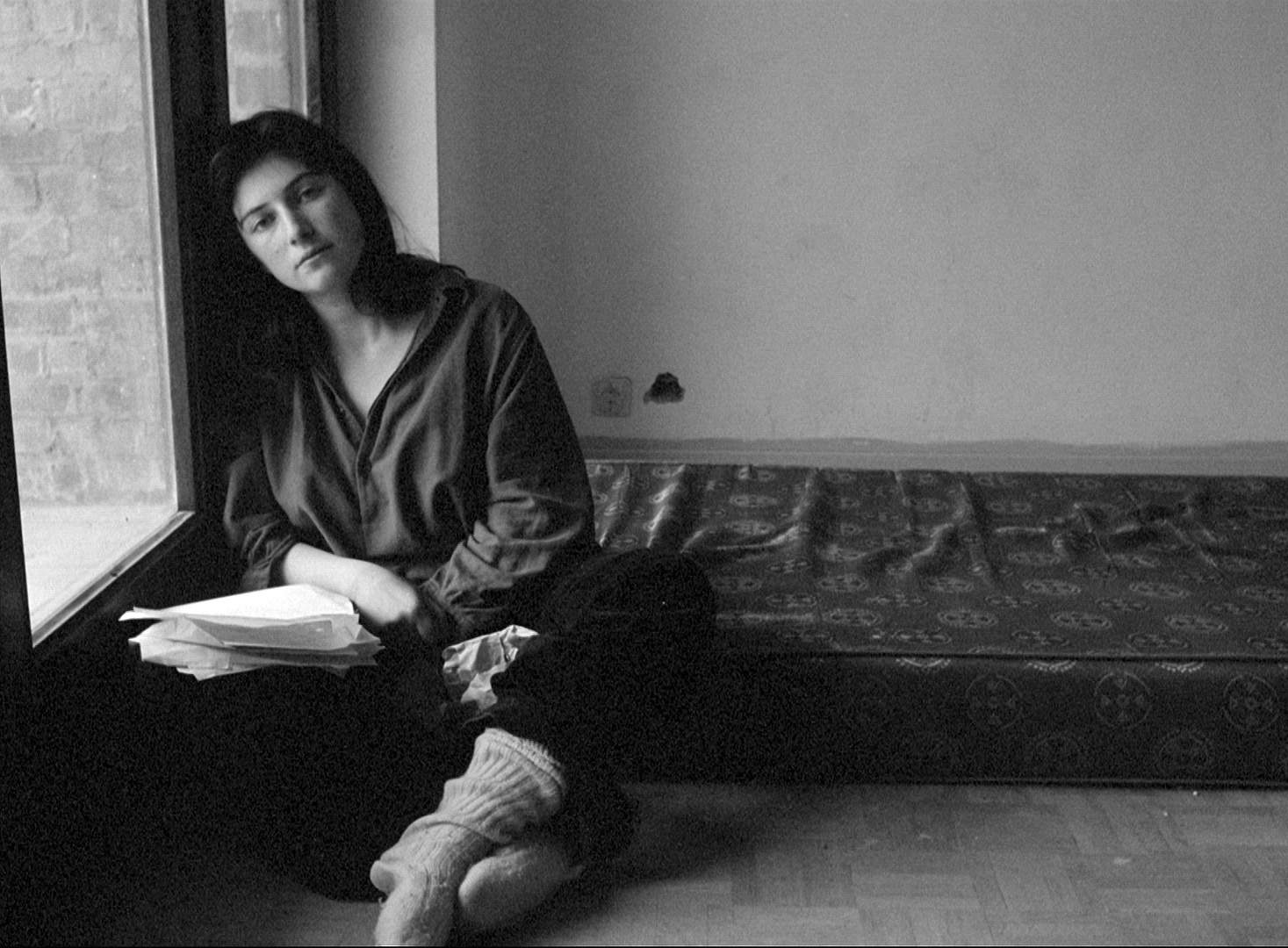

2. Je, Tu, Il, Elle (1974)

Abstract art was created in order to imply, synthesize, and finally gift the ideas that were sometimes ignored by the traditional forms of art. You can call it minimalist, unconventional, or avant-garde. In any case, Chantal Akerman’s “Je, Tu, Il, Elle” is a piece of abstract art. It’s a story without a script, whereas the protagonist is more of a specimen than a character. In its slow takes, simplistic character descriptions, and limited dialogue, this film puts in its epicenter our kind’s textures.

By simplifying and decomposing a humane existence into its fundamental ingredients, an observer becomes able to comprehend our nature, behaviorism, and spiritual needs. In such a way, this movie projects a young woman staying at home for days. She preserves her body by eating sugar. She does nothing more than writing, stripping, curling, and observing. She takes a ride with a stranger, makes love to an ex-partner, and then she leaves. It may seem absurd and empty of thematic content. However, if you puzzle over this picture, it’s just life.

“Je, tu, il, elle” means “me, you, he, she,” and this is what the film is about: no one specific and everyone around you. Akerman’s massage is so simple, catholic, and non-representational that finally, it turns into a very persistent and confident foundation that was built on a forgotten idealistic background. You can watch it and gain nothing. Still, you can watch it and find yourself in it.

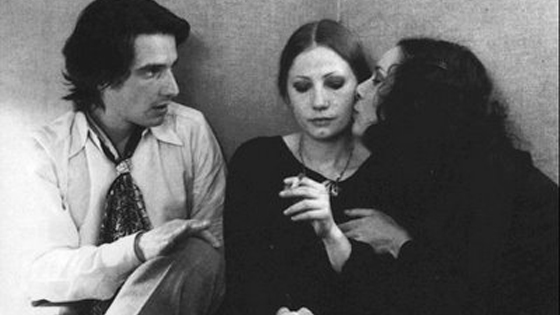

1. The Mother and the Whore (1973)

Watching Jean Eustache’s “The Mother and the Whore,” one meets Alexandre, Marie and Veronica. They all are charming, repulsing, and lovable, alternating these transparent masks of quality in a circle of long monologues and dialogues.

At the end, they all are more than real, representing three different aspects of the same intellectual construction. The film is long, strictly character-driven, and never boring. One could listen to these three main characters talking, arguing, and loving one another over and over again.

Alexandre belongs to the kind of men that women fall in love with. He’s elegant, attractive in an earthly way, and sophisticated to a manageable degree. He doesn’t work and spends his days in cafés, analyzing his philosophy, meeting women, and espying ex-lovers. Marie is a boutique owner who lives with Alexandre, despite his volatile erotic life, and supports him financially. One day, Alexandre meets Veronica, a nurse who talks about her illimitable meaningless intercourses that occurred during a paradoxical search for true love.

At first sight, this erotic triangle appears to be very unstable. Still, as the story progresses, every corner of the triangle needs the other two standing across, so as to create a kind of balancing tension. Alexandre needs a mother to control his careless behavior, but he also needs a liberated female figure to make him feel free. In Marie’s face, Veronica found the reflection of a woman she’d like to be.

On the other hand, Marie realized that she could love a person like Veronica. These three well-crafted and brilliantly embodied characters prove that existing, more than defining a final destination, means to discover and accept a real self.