6. The Graduate

They did it! Benjamin and Elaine have left together and are on their way to spending the rest of their lives together! We see a bit of a conflicted reaction in Benjamin’s face, perhaps because he doesn’t quite know where to go from here.

That’s the more immediate ending that most of us experienced once we finished this Mike Nichols classic the first time. What will this new couple do? Their families are angry with them at the very least (if they do not loathe them). They don’t have much to work with now. Where do they go from here? If you want to feel worse about this ending, consider this.

Firstly, Benjamin was concerned about how his future would unfold at the start of the film. After his innocence was stripped away by Mrs. Robinson, and after his family forced him to find an adult identity by dating and finding work, Benjamin is now rushed into this situation. It was sloppily achieved: a fear he had.

Now, he’s back in the exact same situation, wondering what will become of him. The catch here is he has even less security now. The future is scary, and The Graduate reinforces it the more you worry like its main character.

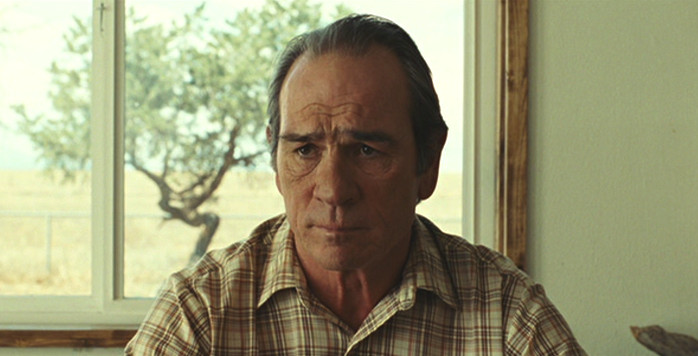

7. No Country for Old Men

We finish this neo western on Ed Tom Bell’s bizarre dream. In fact, we literally conclude the film on the words “[A]nd then I woke up”. The American dream is dead. Bell’s nightmare has ended, but his scary reality is still happening. He’s retired, sure, but he wished to rid the world of evil in his position of power. Anton Chigurh is unstoppable, as he is the human embodiment of death. Bell couldn’t slow him down.

Llewelyn—an everyday man—sure as hell couldn’t prevent his own demise. That’s the important thing to note: Bell represents all law officials, and Llewelyn is all of us honest folk that may come across danger unwillingly; whether we decide to accept the risk of death is on us, but we all have brushes whether we know it or not.

Chigurh is death, we get that. Yet, we now know that Chigurh has been responsible for the deaths or risks of many characters in the film alone. We now understand that No Country for Old Men is a depiction of all of America (or even the world). Bad will always continue. Some innocent people die. Some innocent people try their best to help without much success. No Country for Old Men doesn’t end solidly, because it’s a never ending cycle of humanity’s efforts to prevent evil.

8. The Nun’s Story

In this vastly underrated confessional by Fred Zimmerman, the nun formerly known as Sister Luke recounts her time as a nurse from within a convent; the film displays these memories as a series of events as they happen, and not as a flashback of any sort.

After working in the Congo (where she took care of wounded and sick European patients, and not the natives from the area as she had hoped), she learns that herself sacrifices are not the ones she wants to make, but the ones others expect her to make.

After the death of her father, she finally renounces her title and asks to be discharged from the church. We see her walking away at the end, and that is that. Consider her decision to join in the first place: she wanted to offer herself to God, and to follow in her father’s footsteps as an influential medical practitioner.

She has lost her dad, and her faith has been highly contested. After all of the horrific sights she has faced, who can she turn to for help? We’re not sure, but we hope for the best.

9. That Obscure Object of Desire

After a long story by Mathieu has been delivered to the keen ears of passengers on a train, his ex-lover Conchita reveals that she is on the same train as him. After he poured water on her at the start of the film, she returns the favor by splashing a bucket on him. Somehow, after all of the misery found in Mathieu’s story, the two troublesome partners have come together again. As soon as they reunite, they begin to fight (no surprise here).

After seeing a seamstress sewing together a blood stained, ripped garment, a bomb goes off. The film literally ends right there. We can assume that both people were claimed in this terrorist attack (especially since terrorism is an underlying theme of the film; we knew it was going to come around in some way).

Taking into account the seamstress as their final sight (a symbol of the best efforts to hold together a damaged relationship, a severed society, or a struggling faith), we might have a sadder reality here.

Considering the entire film is the on-off relationship between Mathieu and Conchita, the ending was a gamble. Were the two lovers going to die happy, or hateful of one another? Sadly, by the time the bomb went off, they were both hating one another. That outcome is now permanent, and it’s heartbreaking that they couldn’t mend it one last time.

10. Woman in the Dunes

The recent burst of love for this new wave Japanese classic is because of its lingering ending; one of which is mythological in nature. Niki was stuck in a village against his will at the start of the film, but begins to become integrated in his surroundings. By the film’s end, he finally has the opportunity to leave.

He has a decision to make, though: do I start fresh again and enter the real world, or do I stay here and gift what I know to the other villagers? He makes the ultimate sacrifice and stays. We then find out that he has been “missing” (to characters in the film, not to us) for seven years. We can speculate whether he is happy or not. Has he had the chance to leave within those years, or was that his one and only shot? Is he still there because of his own will? Well, if we’re talking about free will, don’t forget that Niki got into this situation accidentally.

This becomes a philosophical debate: is this actually free will if his options were restricted to begin with? If this is not the same Niki that we knew at the start of the film, is he better or worse now? Sure, his ethics may be in the right place, but his regard for himself and his future is jeopardized now. I’m sure that eliminating selfishness is part of the fable here, but knowing he is permanently in limbo is a little depressing.