5. The House of the Devil

College student Samantha replies to a job ad for a babysitter, hoping to use the earnings to pay for her new apartment. However, when she goes there, Samantha finds herself fighting for her life in a series of terrifying situations, all of which seem to be connected with a fabled lunar eclipse.

“The House of the Devil” was made by Ti West, who wrote, directed and edited the movie. He’s a fan of classic horror films. He understands that if there’s anything more terrifying than a haunted house, it’s a potentially haunted house.

Mr. and Mrs. Ulman are the couple who lure Sam out to their Victorian mansion deep in the dark, dark woods, just in time for a total lunar eclipse. Megan is Sam’s best friend, who gives her a ride out to the house, and reluctantly leaves her there despite suspecting that something is amiss. Like a baby, for instance? Yeah, there is no baby. An old woman – Mother Ulman – is the one Sam has to care for. Weird? Definitely.

The movie does an excellent job of feeling like a movie that was made in the 1980s, with director’s love of the genre shining through every frame, with subtle references to horror films of the past.

It’s not a coincidence that the movie begins with a “true story” style moniker, reminiscent of “The Texas Chainsaw Massacre.” The way everyone has their hair styled and everybody’s choice of clothing suggest that either it’s the 80’s or a retro party. Either way, it’s horror fun.

4. Kandisha

“Here’s looking at you, kid!” should not be the only movie thing that we identify with Morocco. It’s actually a beautiful country that you don’t want to escape from. One of the reasons is that Morocco has a nice movie industry. “Kandisha” is a product of that.

Directed by Jérôme Cohen-Olivar, the movie tells the story of a woman. Shattered by the loss of her child, Nyla Jayde, a successful criminal defense attorney, takes on a case involving a 14th century Moroccan legend, a vengeful spirit named ‘Kandisha.’ That’s when things go downhill.

Trying to find her way back to stability, Nyla agrees to represent a woman who is accused of murdering her husband. While some believe the husband was killed in self-defense, the accused insists she is innocent and that he was executed by Kandisha, a spirit who preys upon men who abuse women. The deeper Nyla digs into the facts of the case, the more she wonders if Kandisha might be real. Kandisha means “Countess,” by the way.

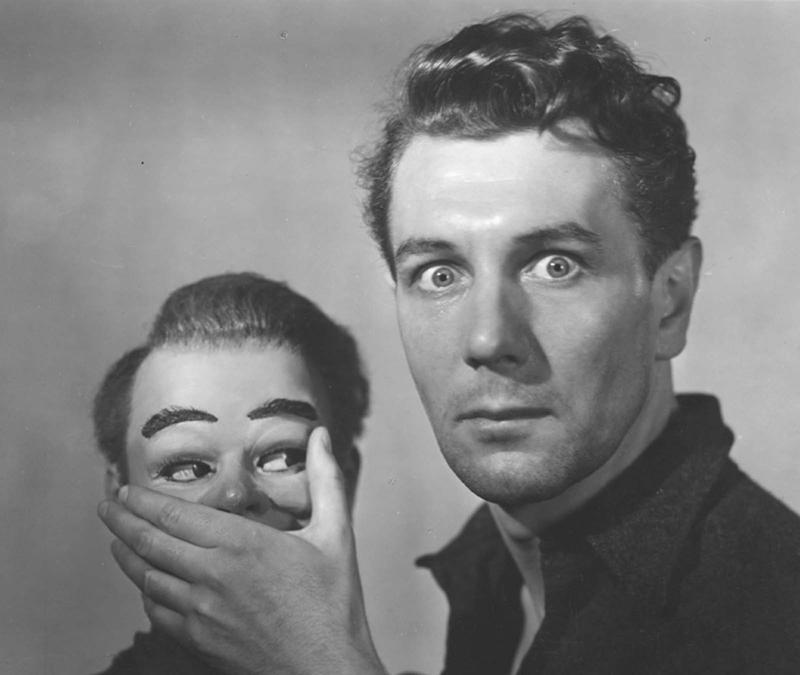

3. Dead of Night

The old ones are the gold ones. This 1945 gem is a horror classic that was overlooked. Directed by Alberto Cavalcanti, Robert Hamer, Charles Crichton and Basil Dearden, the film was produced by Ealing Studios.

Visiting a country house, architect Walter Craig realises that it and his fellow guests are familiar from a recurring nightmare. As the guests share their own tales of the supernatural, Craig is filled with a growing sense of dread.

It is one of just a handful of true horror films of British cinema’s first half-century. It is certainly the most important film in the horror genre until the beginning of Hammer’s horror films a decade later. Released just a month after the formal end of the war, it marks a break from the documentary-influenced realism which had dominated wartime films, particularly from Ealing Studios.

Perhaps the single most influential “portmanteau” film ever made, “Dead of Night” was for years available only in a badly re-edited version, and eliminated many great parts. Even when fully restored, the full effect of the film was lost without the “deja vu” closing credits.

2. El Orfanato

Spain, how I love you! This one is actually my favorite one on this list. Not only is it scary, but it is emotional as well. It makes you cry in an unflattering way. The best horror movie is the one that feeds off all kinds of human emotion, not just fear. “The Orphanage” hits the mark.

JA Bayona’s 2007 horror movie makes the audience hide in a closet, as much for its real human terror as for its supernatural shocks. In the film, Laura and her husband, Carlos, and their beautiful adopted son Simón return to what was Laura’s childhood home, which she shared with other orphans before she was adopted. They plan to turn it into a home for children with learning difficulties, along with Simón, who has to take daily medicine for HIV.

Simón, who is known for having imaginary friends, gets particularly friendly with a boy he calls Tomás. On a trip to the caves near the house, we hear him asking a shadow: “Do you want to come to my house later to play?” Ah, the chills…

This film is child horror at its most emotive. But what’s so potent, after the horror has died down, is the very raw sense of loss and bereavement at the film’s centre. As emotionally wrought as “The Notebook,” what makes you jump doesn’t linger. It’s the humanity of the thing that went bump in the night that makes you shudder for a long while after.

1. Under the Shadow

The end is not near, it’s here! The end of the list, that is. This one is why I defend horror movies against everyone who belittles the genre. It is so rich, so relevant, so mortifying. Living through the chaos of the Iran-Iraq war, Shideh is left alone to protect her young daughter, Dorsa.

When a missile hits their apartment building but fails to explode, Shideh learns from a superstitious neighbor that the missile might have brought in djinns, malevolent spirits that travel on the wind. How culturally terrifying! As a person living in Turkey, this one resonated with me, because we share a similar culture with Iran.

Turkish horror movies are also full of Cins (djinn). They are creatures of another dimension, but they can travel through this one or they can be tied here with a magic spell. They are highly dangerous and fatal. No child’s play. I want to take this moment to advise you to watch Turkish horror films as well. They are underseen and quite scary. Especially “Dabbe” series and classics like “Büyü” or “Musallat.” Let’s not forget “Baskın” by Can Evrenol.

“Under the Shadow” blends genres to deliver an effective thriller with timely themes and thought-provoking social subtext. Like what it is to be a woman in Iran or in any country, for that matter. The monsters are obviously metaphoric, and director Babak Anvari hammers home that idea by giving the chief specter the amorphous shape of a giant, fluttering burka.

From a filmmaker who grew up in Tehran, this choice feels especially pointed: the threat isn’t just to the life of a mother, but to the future of her child, who might be swallowed whole by the repressive mores of her culture—the alternative “parent” hoping to raise her.