6. 12 Years A Slave (2013)

There comes a moment after Solomon Northup played by Chiwetel Ejiofor, is captured into slavery and states “I don’t want to survive, I want to live”. Unfortunately due to to history, this man was living a free life and then taken into slavery, hence the title, thus beginning of his twelve years of captivity.

Every person on this earth wants to live the best life possible yet due to fate and circumstance sometimes, it always doesn’t play out that way. In this case, due to the shameful and despicable act of owning people and treating them as property, this man, like thousands of others, had to see the value of being a human being stripped away from him and the longing to achieve his freedom once again. As Steve McQueen unfolds his intimate, brutal, and poetic epic intimacy of this man’s struggle to gain his value, family, and ultimate life back as a human being, we witness the brutality that humans have on one another.

After beatings, abuse, and a scene that is too cruel yet can’t look away hanging scene, Solomon truly sees how delicate human beings can be. He has seen the free and oppressed side of American life in the 1850s, therefore, how every human being – man, woman, and child – simply longs to be a human being. What does that entail, do anything morally and ethically in life without oppression and mistreatment such as slavery by one human being to another.

“12 Years a Slave” is a film that should be seen not only for an accurate representation of American history, a man’s struggle to regain his freedom, or for a phenomenal film but for the sole purpose of seeing how a human being’s life is so fragile and should only live in freedom to discover their purpose and essence in life, not through the act of surviving, but through the act of living.

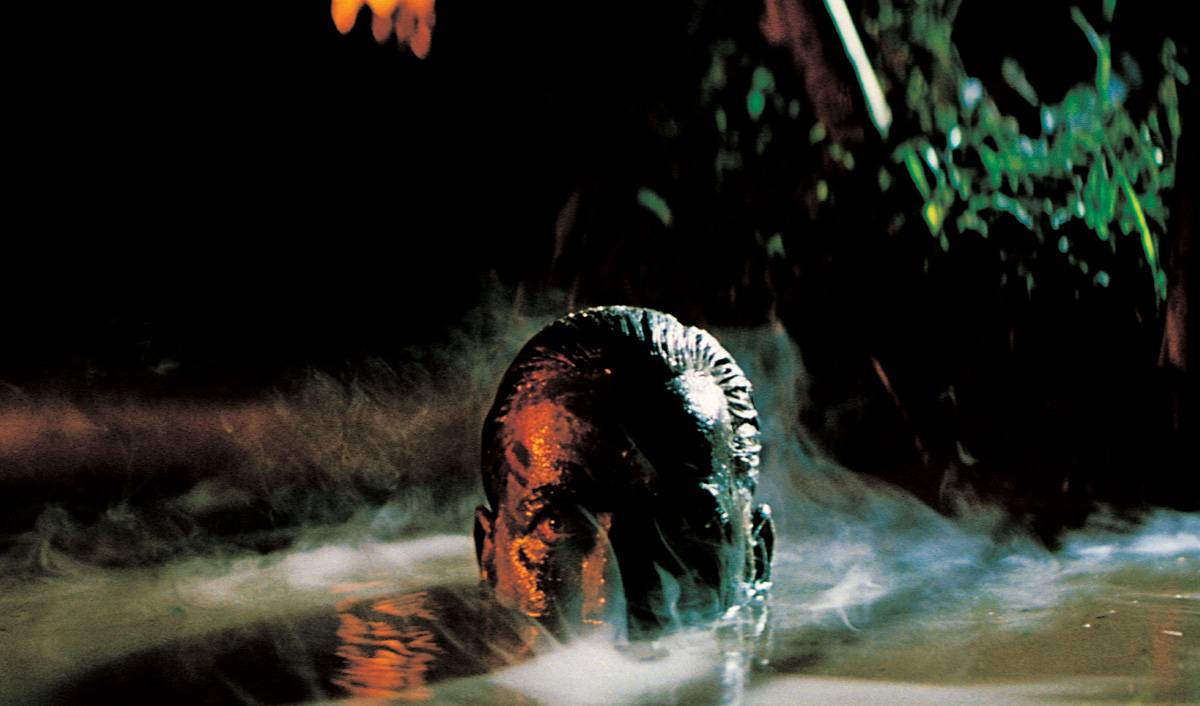

7. Apocalypse Now (1979)

War is a reality that exists and out of this gruesome act, an individual experiences a mind shift that results in chaos, intoxicating behavior, suffering, and existentialism. Francis Ford Coppola’s ‘Apocalypse Now’ captures the madness of those individuals as they face choices of morality and survival in this cinematic masterpiece.

Who can rationalize one’s behavior in this film and state they are not acting like a human being should? Take Dennis Hooper’s photojournalist who pontificates while he worships Kurtz, alongside the natives. Or Robert Duvall’s Kilgore wanting to see surfing escapades during an operatic attack on a Vietnamese village. Or the crux of how Martin Sheen’s Willard enters his heart of darkness to terminate the Colonel’s command.

Sayings like ‘This is better than Disneyland’. Or finally, Brando’s Kurtz as a rogue officer now a godlike figures amongst native peoples deep in the Cambodian jungle. These are just some of the individual’s behavior as they alter their longing to stay alive and survive. But why and how?

Despite being labeled a war film, the film explores how desperate human beings want to stay alive. They will do anything, no act is too gruesome or wrong for their own prolongment of life. Who can blame them? Since their actions of killing the innocent or corrupt or just bystanders lost in the useless war, their minds change and they see a shortened longing for the purpose of themselves. Their goals and minds change but it is still out of the essence of being a human in the world because they don’t want it taken away from them in an unjustified death.

Look at Willard as his mission is to kill Kurtz. He keeps roughly silent to himself as he reads Kurtz’s dossier and tries to figure out the questions why this man went rogue and why his government sent him to assassinate him. But as they travel further down the river, Willard becomes uncompromising towards his mission, nothing will stand in his way – not a screaming Vietnamese woman he shots, the death of his accompanying shipmates or even a tiger.

In the normal world, these things would surely turn one away. But in Coppola’s darkness and insanity of war, it truly brings out how people will do anything to achieve their mission and go on with their lives, no matter how altered their minds will be afterwords.

8. AI: Artificial Intelligence (2001)

Steven Spielberg taking over for a film after the death of Stanley Kubrick in a science fiction version of Pinocchio more or less, where a child android who looks like a real boy has the ability to love and feel like a human being – a promise is delivered. A film that is often overlooked in the scheme of things but continues themes explored in other science fiction films but this time grounded in love. Spielberg draws his attention from Brian Aldiss short story and we see how a robotic boy dreams of being a true human.

There are certain moments throughout the film where the boy, David, played by Haley Joel Osment tries to be human, but more importantly accepted by his adopted family. He laughs awkwardly and harder than a usual boy and tries to digest food but can’t, because he isn’t human. Most crucially for David, he wants the love of his mother. This feeling cannot be undone in David’s search for meaning as his mother wants that for him too, to be accepted as a real human.

Out of David’s quest from circus to robot roundup to extinct frozen Manhattan, we see through David’s eyes what are the most crucial aspects are to be human. Despite looking like an innocent young boy, and relatively he is, he gets freighted and scared but more importantly he loves and feels the connection to his mother.

At the end, in Spielberg fashion, a happy, warm ending takes place where David and his mother share one day together in a recreation of her and the memory of their home. In the final act of the film, we experience that same feelings of love that David feels. He behaves like a real boy and we experience this feeling despite the bleakness of the world he passed through. The film achieves the human being affection and longing for love in which is the most identified feeling to be human and longing to be human.

9. The Elephant Man (1980)

All humans look alike. All humans look different. Some more than others, and in the case of John Merrick, born with severe deformities in Victorian London, he is not treated as human by society. Merrick, played with such humane profoundness by John Hurt, becomes the subject of a circus, a freak show, a la ‘The Elephant Man’, and is show cased as sorts until Anthony Hopkins’ Frederick Treves takes under his care.

This film by David Lynch explores the very essence of what makes a human being. Yes, John Merrick might look different than anyone else but before anyone asks questions, they treat him like second nature, an animal, or inferior being. As the story progress, we discover John is quite an intelligent and caring person and is slowly welcomed into society by a small group of individuals such as Anne Bancroft’s Madge Kendal.

After walking around London with a cap and bag over his head for his entire life, he starts to walk as his inner self, a true man. This leads to one of the most heartbreaking scenes in cinema, as John Merrick is literally spiraled down into the subway by a crowd of curious and pushy Londoners and is trapped internally and physically by the crowd, he pleas a desperate “I am not an elephant! I am not an animal! I am a human being! I am a man!” as he collapses to the floor.

He declares it himself, he comprehends, understands, and feels everything around him as anyone does. Despite the fact that looking unique or say different than everybody doesn’t disqualify him as a human being or make him any less. It actually shows the true soul of human beings is inside oneself, not on the outside.

The film shows the very quintessence qualities of a human being, internally and externally, portrayed by Hurt and the real life persons of Hopkins and Bancroft. John Hurt summoned it best about the film “if you aren’t touched by this movie, you’re not the kind of person I’d want to know”.

10. Wings of Desire (1987)

Wim Wenders’ poetic, dreamy masterpiece follows angels, primarily Bruno Ganz as Daniel, as they observe people and listen to the desires, inner thoughts, and longings of those people in West Berlin. The roving camerawork and mumbling overlap of voiceovers with the beautiful black, white, and color increase the capturing of what the essence to be a human being is.

Throughout the film, the thoughts of the people are revealed – deep questions and statements such as ‘desire for love’, ‘why do I live’, ‘I hope, I hope, I hope’, ‘I’m happy’ and simple mundane sense such as ‘it’s really cold’ ‘old human expression’. These inner thoughts reveal what humans think and feel as the angels can only observe. Of course, they have their opinions and feelings on the people they watch above or right next to but despite leaning over them, they don’t know what the feeling of placing their hand on someone in need actually feels like.

The question goes beyond the physical means because they can’t interact with anybody and share an experience together. It’s only one sided all the time. The main concern for Daniel is he has fallen deep in love while admiring a trapeze artist, Marion.

As the film continues as we jump from an old man walking the streets with World War II archival footage to a suicidal young man on a rooftop to students in the library to Peter Falk playing himself enjoying the taste of coffee and cigarettes as he address Daniel, invisible to him in sight but tangible in feeling. We slowly learn the poetry of what it means to be human, all the emotion that plays out in our head, no matter how small or big, it means that we are alive and in the moment.

As Daniel decides to become a human, he shares another beautiful encounter with Peter Falk, this time in the flesh, he finally lands up with Marion. Through the motif of poetic exposition of the connection between the two, Daniel assists Marion twirling in the sky, with her above him this time, as Daniel’s final thoughts of voiceover in the film are ‘the amazement about man and woman, amazement has made a human being of me. I now know what no angel knows’ proves the essence of feeling and connection through the longing of being a human being.