When talking about controversial movies, Pier Paolo Pasolini’s “Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom” has its permanent ticket for the first spot. Even after four decades, the film hasn’t lost any of its radical effect with its unmatched illustration of perverted human cravings.

Building their personal realm of sadism, violence and murder during the Republic of Salò between 1943 and 1945, four wealthy fascist libertines kidnap 18 teenagers for the sake of their own perverted desires.

Much has been written about the movie, its impact and similar films. There is, of course, Gaspar Noé’s “Irreversible” with a hard-to-look-at rape scene, lasting for more than 10 minutes. One might think of 2008’s “Martyrs,” another representative of the blood-soaked French New Extremity movement.

There’s Lars von Trier with his “Antichrist” and its crushed testicles, cut-off clitoris, and descent into madness, or the entirety of 2010’s “A Serbian Film.” But while all of these movies definitely illustrate similar abysmal actions, they are products of the 21st century, a fact that obviously reflects in another aesthetics.

Therefore, the following list will focus on some less popular choices, and with an eye on similar aesthetics and themes instead of the pure depiction of cruelty and violence. In addition to some outstanding movies, this list contains some examples of similar movies that didn’t manage to match up with the quality of Pasolini’s last film. Spoilers ahead.

1. La Grande Bouffe (Marco Ferreri)

The plot of “La Grande Bouffe” is as simple as the title suggests. Four wealthy men arrive at an opulent mansion in order to commit collective suicide by eating as much as possible. In fact, their desire concerns every form of oral consumption. Therefore, the last days in the men’s’ lives result in a repulsive orgy of lust and gluttony beyond every sense of continence and frugality.

The movie isn’t interested in explaining the characters’ backstories, but the unadorned depiction of obscene profusion and Western waste mentality. It illustrates the dark side of hedonism, a place where the voracious grimace beyond self-determination and freedom gets carried away to sadomasochistic appetites.

Released in 1973, the movie was made under the influence of the sexual revolution and omnipresent possibilities of pleasure. There’s a reason why the four men are tired of existing: the constant abundance has robbed them of their enjoyment of life. Neither delicacies nor female company can add auspicious nuances to their existence. It’s quite metaphorical that legal stimulants like food are the men’s choice for their collective orgiastic passing, illustrating the reverse of newly gained freedom in the late 60s and early 70s.

The social criticism in “La Grande Bouffe” is obvious and accompanied by an aesthetic of disgust. Constant waves of belches and flatulences find their climax in a toilette’s blockage and subsequent fountains of feces. An interesting picture for the negative sides of hedonism that can’t be washed away, but always find their way back to the surface.

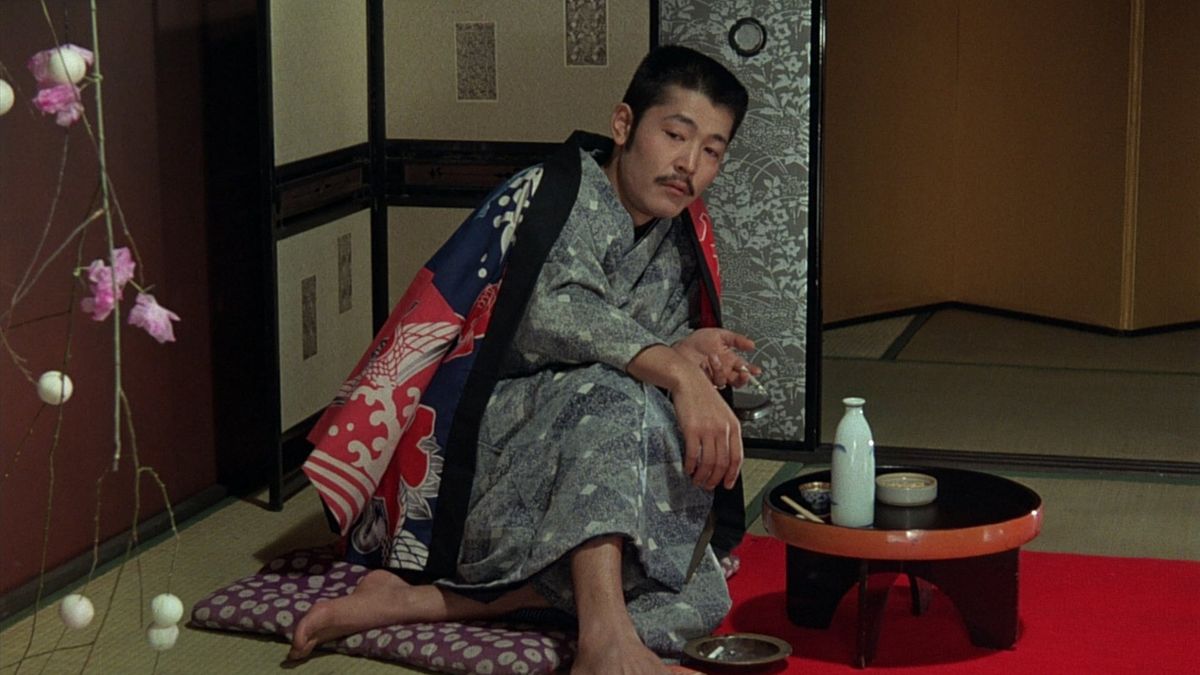

2. In the Realm of the Senses (Nagisa Oshima)

Together with “Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom,” Austrian filmmaker Michael Haneke named this movie as one of the only two examples of adequately presented sexuality in the movies. He doesn’t refer to the art of the sexual interactions between the two protagonists, but the way Nagisa Oshima illustrates them. Just like Pasolini’s film, his visual approach is a more analytic one, without enriching the portrayal with emotional values or subjective perspectives.

Based on the true actions of Abe Sada, the movie starts with the housemaid beginning her new employment at the court of Kichizō. Besides her daily duties as a servant, she has to provide sexual favors for her new master. Subsequently, both he and her slave start a sadomasochistic relationship, with her increasingly claiming the ownership of her object of desire. Losing reference for reality, the dangerous liaison ends with Abe cutting of her master’s genitals.

Aside from both movies’ carefully composed mise-en-scene, alternating between cruel drabness and opulent beauty, there are a bunch of similarities. In Oshima’s film, the protagonists treat the human body as something one can claim possession on (Kichizō referring to his penis as “practically it belongs to you,” with Sada answering, “You’re right, it does belong to me”). The reduction of the human body to an object is extended by Pasolini by letting the four fascists treat a whole group of people as their property, as things for their sexual pleasures.

What’s also interesting about “In the Realm of the Senses” is Oshima’s disinterest in the characters’ backstories (there’s just one short scene about the protagonists talking about their parents).

Just like in “Salò,” the movie is about the current actions, without justifying them in the characters’ past. It’s about the now, the actions in the present. Working as an attraction for one party and the destruction for the other, if it is acted out in abusive extremity, power can wipe out the past and even the future. Both directors depict this concept by illustrating extreme poles of obsession, the dynamics of desire, power abuse over other human beings, and death.

3. The Night Porter (Liliana Cavani)

Just like “Salò,” Cavani’s “The Night Porter” from 1974 connects the deformities of fascism with abnormal sexual desires. In the course of the reprocessing of National Socialism, the connection between concentration camps and systematic sexual exploitation and humiliation emerged.

In form of a perfidious reward system, the female body was exploited to control the prisoners’ working capacity. Aside from these methodic crimes, high-ranking NS officers took ruthless advantage of the imbalance of power to their subordinate inmates. This is part of the premise of “The Night Porter.”

More than a decade after World War II, a concentration camp survivor and her tormentor, currently a night porter in a Viennese hotel, meet again and fall back into their sadomasochistic relationship. On a visual layer, both movies share a similar aesthetic, which is not surprising, regarding the close release dates.

But instead of “Salò,” the movie doesn’t get the right tone for its delicate substance matter. Especially the non-diegetic use of music and the sometimes subjective camera work arranges for the fact that the movie declines into cheap gratification instead of being a serious illustration of sadistic behavior.

Furthermore, the authenticity suffers from the set design, revealing budget difficulties. While most of the other movies on this list have a certain standalone quality, “The Night Porter” is a great example for distinguishing the strengths of “Salò.”

4. Henry, Portrait of a Serial Killer (John McNaughton)

A female body, her head down in an idyllic streamlet. A naked woman in a bathroom, blood-covered with a crushed bottle of coke penetrating the right side of her face. Disturbing images of blood-drenched murders. The sacred sound of spheric synth pads and the victim’s last screams. What might be the message behind this contra-punctuated melange of image and music? Was the death some kind of salvation for the victims in view of their psychopathic tormentor? The death as only hope for deliverance.

Henry’s victims shared this with the teenagers of “Salò.” From the very first shots, one is aware of the hopelessness, the pure certainty of death, the pain the victims will suffer as well as the teenagers did in “Salò.” But there’s another aspect the first shot’s reveal. The camera zooms out, creating a literal and emotional distance for the audience.

Even though some distinct differences separate the work of director John McNaughton and the one of Pasolini, there is a common ground between both films, perfectly symbolized by the movies first shot.

As well as Pasolini did in “Salò,” McNaughton portrays his characters and their stories in unemotional frames. Quite like the name suggests, it’s a portrait, not an entertaining thriller – as well as “Salò.” The horror lies within the realism of the shots, the scene’s approachability. The movie rejects classic suspense elements, showing a much more analytic picture instead.

It is a cliché-negating character study, offering some interesting thoughts on the presentation of violence. With its use of videotapes and the way Henry’s companion feels sexually stimulated by watching violent acts on screen (in fact, himself humiliating and killing a woman), the film works as a critique on the portrayal of violence in cinema (one is reminded of the works of Michael Haneke, especially “Funny Games” and “Benny’s Video”).

The spare places where Henry walks are mirrors of his emotional solitude (on a psychological layer, the movie has been praised for its accurate illustration of a psychopath, not capable of engaging with the world around him and feelings of any kind). Chicago’s grey winter and its desaturated mood are heralds for the unpreventable. There’s no happy ending.

As Roger Ebert said, “Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer” “is intended to illuminate, not entertain.” He’s totally right with that and without intending to, he sums up the similarity between this film and Pasolini’s last.

5. The Virgin Spring (Ingmar Bergman)

At first sight, Ingmar Bergman’s 1960s movie doesn’t seem to share a lot with Pasolini’s most controversial film. But especially in terms of subject matter, there are some distinct parallels to be discovered.

With “Irreversible” being released more than 15 years ago and Wes Craven’s “The Last House On The Left,” which is actually a remake of “The Virgin Spring”, released more than 40 years ago, today’s audiences are used to the depiction of rape and murder. But in 1960, showing terrible actions like that in cinemas wasn’t an everyday occurrence.

“The Virgin Spring” was one of the first movies that contained such a realistic and therefore disturbing illustration of three prowlers raping a teenage girl. Just like “Salò,” the movie had difficulties with age rating in several countries.

In both films, the violent acts – in Bergman’s film, the rape, in Pasolini’s, every form of torture one can imagine – are mainly for the sake of the perpetrators’ pleasure (even though there is a will of self-enrichment in “The Virgin Spring”). But there is a distinct difference between these two movies.

In “Salò,” the violence doesn’t entail a punishment for the culprits. In “The Virgin Spring,” all three brothers are killed in an act of vengeance by the dead girl’s father. While Bergman’s movie ends with the possibility of forgiveness for him (a fact Bergman dissociated himself from in the years after the movie’s release), in “Saló” there’s no hope for any kind of absolution, not to mention justice.