6. The Cook, the Thief, His Wife and Her Lover (Peter Greenaway)

Peter Greenaway’s “The Cook, the Thief, His Wife and Her Lover” is a cinematic examination of excess and suppression. In terms of its theme, his movie ranks in same spheres as Pasolini’s.

While watching the two films in consecutive order, one could get the impression that the explicit depiction of human excrement is a common feature in European cinema. A few minutes into Greenaway’s movie, its continuing sequence of repulsiveness starts with Albert Spica, a bullying co-proprietor of an exquisite restaurant, forcing a man to eat his own feces and peeing on him.

This is the kickoff for a lot of equally disgusting incidents, including a truck full of fish and meat, left in the restaurant’s lot abandoned to rot. The mesmerizing production design definitely ranks in one league with the work of Dante Ferretti (who can count three Oscar wins in total) for “Salò.” Especially the restaurant is an opulent mixture of painting-like baroque aesthetics, stylized bizarreness and surrealism.

It’s especially the restaurant where the similarities between both movies come to light in its brightest form. The banquet scenes in both films work as an interestingly parallelized parable for excess, both with different subjects but a similar message. Treated in wrong extremes and with the purpose of reigning with power over others, all pleasures can be exploited and transformed into something contrarious.

7. Salon Kitty (Tinto Brass)

The similarities between “Salon Kitty” by Italian filmmaker Tinto Brass and Pasolini’s last film display while examining both movies’ plots. A group of young people (in case of “Salon Kitty,” all female) is forced to execute sexual practices in order to satisfy the will of some powerful men.

As a matter of fact, there are some distinct differences. In “Salon Kitty,” the men’s intentions are of a political nature (at least on the surface), while in “Salò” it is mostly about the simple satisfaction of perverted pleasures. Furthermore, the young people in Brass’ movie give in because of a similar political ideology, in contrast to the teenagers in “Salò.”

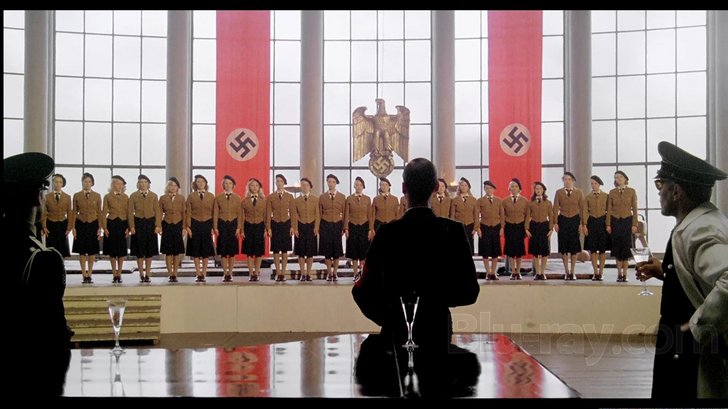

Already at the movie’s beginning there’s a scene that perfectly summing up the huge problem with “Salon Kitty” and its way of dealing with the delicate subject matter of National Socialism, forced prostitution and perverted sexuality. The young women, standing at military-like attention in front of flaming torches and enthroned NS-insignia. The systematic abuse of power in connection with misused sexuality is literally presented in glorifying light, in contrast to the completely different illustrated but thematically similar plot in “Salò.”

Unnecessary cuts and optic tricks, like changing from color to black and white to increase the measure of manipulation, while taking away the needed moral distance. Aside from these technical flaws, even the narrative’s concept fails to meet the thematics standard. The women present a circus-like performance with a group of selected men, resulting in some kind of comedic montage. Interrupted by musical pieces, the whole movie is as well as “The Night Porter” a great example for how a serious theme can be harpooned by an inadequate implementation.

8. The Piano Teacher (Michael Haneke)

“Look, Pier Paolo Pasolini’s film “Salò” […] scared me so much that I was sick for 14 days. Completely wiped out. To this day, I haven’t drummed up the courage to watch it again. Never again did I look into such a deep abyss and rarely have I learned so much.” With these words, Austrian auteur Michael Haneke describes his cinematic experience with this article’s subject.

Therefore, one isn’t surprised to find similarities between his oeuvre and Pasolini’s film. There are several movies by Haneke that could be described here in terms of a cinematic relation to the Italian filmmaker, but in terms of the presentation of dysfunctional and perverted sexuality, his award-winning film “The Piano Teacher” from 2001 might be the best choice.

Based on the same-named novel by Nobel Prize-winning writer Elfriede Jelinek, “The Piano Teacher” follows Erika Kohut, the title-giving piano teacher. She lives in a small apartment with her mother, who seeks permanent control over her daughter’s life. Her repressed sexuality finds its way during secret visits at a porn cinema, or when she spies on copulating couples in the darkness of a drive-in cinema.

In the course of her work at the Viennese conservatory, she meets an ambitious and talented student named Walter Klemmer, who starts to ask her out. But instead of starting an emotional relationship, she wants to involve him in a sadomasochistic game, a fact the young man can hardly cope with.

It’s Haneke’s approach to ban every emotional excess or technical manipulation. Instead, his movie works as an analytical examination of the protagonist’s attempts to deal with her authoritative mother and her masochistic desires.

Even when most of the scenes can’t surpass the terror of Pasolini’s “Salò,” there are some moments where the great performances of Isabelle Huppert and Annie Girardot, as well as Benoît Magimel, and the shot’s simplicity and realistic approach make for a shocking experience.

9. The Wicker Man (Robin Hardy)

Described as “the ‘Citizen Kane’ of horror movies,” “The Wicker Man” from 1973 by British director Robin Hardy gained a cult following in the decades after its release. In order to get to the bottom of a young girl’s disappearance, Sgt. Howie travels to Summerisle, an isolated island. There, he is confronted with the strange habits of the inhabitants, their constant ignorance of his questions, and an odd loyalty to the island’s namesake.

Everything that happens here seems to be dictated by Lord Summerisle, whose ancestors bought the island generations ago. While Sgt. Howie is a few steps away from solving his case, he stepped right into a nest full of bizarre traditions and a religious cult.

On the surface, the movie and the work of Pasolini might not have much in common, but especially in terms of theme, there are some parallels. Both films focus on a group of people who built some kind of autonomous society, a detached hideaway faraway from law and its executive. In “Salò,” the four fascists and their entourage built their realm of terror and sadomasochism in order to enslave the teenagers for their desires.

In “The Wicker Man,” an ancestor of Lord Summerisle created the cult of the Wicker Man to get the people’s approval for his plans. It seems like the orbit of court is far exceeded and in both cases, the movie ends without correcting this imbalance.

10. Angst (Gerald Kargl)

Based on the true events of Werner Kniesek, 1983’s “Angst” tells the story of an unnamed psychopath whose imprisonment comes to an end. But instead of building a new existence, he reverts back to his old ways and attacks a family in their isolated home. After the assault, he decides to head off to new murderous actions with three dead bodies in his trunk.

While there are numerous differences between “Salò” and “Angst,” like the unconventional camera work, the voice-over narration and the electronic score by Klaus Schulze (former drummer of Tangerine Dream), some features bridge between both movies.

While Pasolini’s analytic approach works especially on a visual layer, the Austrian movie utilizes voice-over narration for this purpose, transforming it into some kind of a cinematic psychogram with literary nuances. Working as a mixture of memories from his childhood as well as his imprisonment and personal justifications, the voice-over gives insight into the character’s mind. It becomes clear that he projects his familistic differences from the past in his present victims, while channeling huge waves of satisfaction.

With its desaturated color palette and the bleak environment of 1980’s Austria, the audience has from the very first minute a feeling of constant hopelessness. The movie unfolds a claustrophobic world and the protagonist’s delusional state of mind. And like “Salò,” it is a depiction of fear and the desire for power.

Author Bio: Berlin-based Luc Hinrichsen works for a film distribution and production company. Besides that, he’s an aspiring screenwriter and director always curious about enlarging his knowledge about film and its history.