6. Lancelot of the Lake

Much like how Japanese directors like Masaki Kobayashi tried to explore and deconstruct the fundamental samurai values, in “Lancelot of the Lake” we observe as Bresson explores the Arthurian myth and really deconstructs its knightly principles while maintaining its main narrative direction.

In this movie, we experience a completely different Bresson than what we are used to, stripped down from all the spiritual dilemmas usually found in his other movies, like the aforementioned “Diary of a Country Priest” (1951).

Instead we have a raw, brutal version of the seventh chapter of Sir Thomas Malory’s “Le Morte D’Arthur” and the knights of the round table. It’s in this primitive depiction of the disreputable knights (after the failure of the quest for the Holy Grail, described on a title screen at the beginning), made with the help of reserved shots in the representation of the knights in action and the realism of a mainly amateur cast, where we can find the lyricism in this (surprisingly?) faithful adaptation of the classic story.

It is probably more disconcerting than disturbing, and maybe one of the more nihilistic works from Bresson, despite it being way less known than most of his other works. Yet, we can definitely understand, even if we can’t completely deconstruct the movie itself, that it teases the viewer into not only envisioning the knighthood as something more realistic and human than romantic (that often we refer to with mindless nostalgia) but in many aspects relate this work to other movies in his filmography.

We can then perceive the persistence of more specific themes, like the procedures of a group of working men (the knights in relation to the pickpockets in “Pickpocket” in 1959), the relation of someone on an important position (in this case, Guinevere, much like Joan of Arc in 1962’s “The Trial of Joan of Arc,” for instance), his/her sexual tensions, and what this celibacy says about these characters’ profiles.

If you are in the mood for a nihilistic and complex modernization of the Arthurian myth, this underrated gem will fulfill that need. If you are expecting something like “Excalibur” (1981), maybe you should look somewhere else, because despite being classified as a fantasy movie, this is a determined arthouse movie with harmonious yet unexpected cinematography and art direction. In addition, a realism and relevance not always foreseeable in this cinematic genre.

7. Taste of Cherry

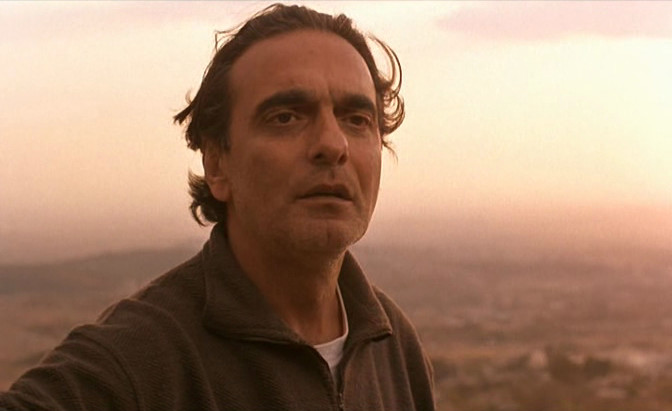

This Asian entry on the list is arguably the most notable movie by the Iranian master Abbas Kiarostami. Yet another Palme d’Or winner on the list, and yet again a movie that can be hard to recommend given one must be in the right mood for it. It’s a meditative movie about suicide and existentialism that is stripped down from most traditional methods to keep the viewer engaged.

It is hard to talk about a movie such as “Taste of Cherry” without making it sound like watching it is a chore, but it can’t be dismissed just as being boring (as some REALLY famous movie critics reviewed it). It is a movie mainly about a man going around Tehran searching for something you initially don’t understand, but you are quickly introduced to Badii’s (Homayoun Ershadi) intentions.

It is also a movie that carves a landscape and presents a world that is harsh and an apparently inconsiderate society. There is close to no character development and this works with its main tone and atmosphere. There is a sense of isolation and loneliness we can only presume from Ershadi’s face, and the way the camera follows his truck around the desert.

It is one of the simplest movies treating one of the hardest aspects of human life. By the end of the movie, you have yet another shot of Badii, now crumbling in tears, and it is hard as a viewer not to follow after him. It is a harrowing piece of work, more upsetting than it is disturbing, despite it being incredibly beautiful and peaceful. Whether it’s because of its cinematography or simply because of its poetry and the realism of its main character.

8. Morvern Callar

This British movie directed by the sadly underappreciated Lynne Ramsay is probably one of the greatest forgotten movies of the 2000s. “Morvern Callar” is a book adaptation of a journey of self-discovery that is as mysterious and disturbing as it is enthralling and utterly engaging. Samantha Morton plays Morvern, who is presented to us curled up against her boyfriend, who had just committed suicide.

What is brilliant about the movie is that for every action we see of Morvern, we ask a new question. The movie evolves from being a mystery about a suicide to a complex character study that is never clear. Much of the credit must go to Morton on her most intricate role yet. Why does she put her name in the novel left by her boyfriend? What impact does this suicide have on her psyche? Where is Morvern Callar going? All we know is that she and her girlfriend are going “somewhere beautiful.”

Ramsay initially presents a dim and gloomy Glasgow, but throughout the movie there are a lot of changes in scenery, from clubs to rural southern Spain. There is a subconscious level in the treatment of images by Ramsay. The use of color, movement, soundtrack, all of this combined creates a unique feel to her work, feeling way more subtle and intelligent than her early movies.

The lyricism and beauty of “Morvern Callar” relies on its mysteries. Mysteries that will not be answered directly by its creator, but instead mysteries that are fascinatingly set up, often with a purpose. We are left unsure if we find Morvern’s behavior scary or just human, or maybe both. What we are sure of, though, is that after watching “Morvern Callar,” we are left with a new standard for what we expect from a movie character.

9. Solaris

Andrei Tarkovsky is one of the greatest filmmakers of all time. His movies have a greater feel to them, not only cinematically speaking but also philosophically. “Solaris” may well be one of his most complex cinematic takes on consciousness, identity, and existentialism.

Originally a photographer, Tarkovsky translated that experience into creating beautiful moving images that are fascinatingly haunting. Not wanting to spoil the ending of the movie, its last frames are some of the most ambiguous and poetic, giving the viewer a feeling of dread toward its big philosophical ideas. It is the perfect example of what we refer to with the title of this list.

This is a movie about so many things and yet it is depicted so peacefully and is paced so calmly, that even being so, it still leaves us really confused by not only its ambiguity but by its complexity. What is Solaris? Did Kris (Donatas Banionis) give up on life or is he stuck in the limbo between his memories and reality? What makes a real person real? There are few words that can describe this movie, but one thing is that it is exhausting.

It is a long movie that requires a lot of patience and effort from the viewer for its questions to work. Not necessarily for its questions be answered, but to at least most of its questions being defined. It is, though, a beautifully crafted piece of work with visually impressive cinematography by Tarkovsky’s regular Vadim Yusov and great performances by its two lead actors.

If you are in the mood for a profound philosophical movie, not unlike the ones that one crazy teacher of yours from philosophy classes always talked about but no one had heard of, this is probably the most accessible of Tarkovsky’s movies. If you are expecting something like “Star Wars” you should search somewhere else. Think of “Solaris” as the Soviet counterpart to “2001: A Space Odyssey,” but instead of being obsessed with technology, it’s obsessed with the existential dread of being alive.

10. Dekalog

Some will say that this is a bit of a cheat as it was originally meant to be televised, but it should be remarked that “Dekalog” is one of the most cinematic television shows ever created. Divided into 10 parts as there are 10 commandments, “Dekalog” is probably Krzysztof Kieslowski’s magnum opus.

There is something greater about all 10 hours of “Dekalog,” but if there is something worth noticing, it’s that if you want the full uncut Kieslowski experience you should skip the fifth and sixth episodes and watch instead his “A Short Film About Killing” (1988) and “A Short Film About Loving” (1988), as these episodes are stripped down (but still coherent and with all the agitating qualities of the full features) versions of these two movies.

It will make you think, cry, and question yourself. It will change you and how you perceive cinema and art in general. Kieslowski manages to harmonize every part of what makes cinema what it is in a way no other director can. The music with the movement, the writing and the actors, the cinematography. These episodes are quintessential Kieslowski together with the Trilogy of Colors. It is a show that should be experienced and should be way more relevant and discussed than it is today. Make a change, if you haven’t yet, and go watch it.

Author Bio: Manuel Oliveira is a Portuguese literature student who spends most of his time in the FCSH college talking about either heavy metal music or underground movies. Despite enjoying reading a book and going to concerts, what he really likes to do is spending a Saturday afternoon in the cinema.