5. Autumn Sonata (1978)

Watching Ingmar Bergman’s films, one could easily be bowled over by his brilliant allegoric compositions and poetically profound approaches toward various intellectual topics. But mainly, Bergman numbs his audience’s cerebral nerves with his masterful fashioning of both pragmatic and complex characters.

The quivering construction of sentiments and repressed anger that it is “Autumn Sonata” fuses all of these virtues with great ease. It may be one of his most distinctive late-career fruits, yet it doesn’t lack in the springing emotional and idealistic depth that the great Swedish director usually provides.

In the foreground, the plot refers to the dysfunctional relationship between a retired successful pianist and one of her daughters. Charlotte, superbly embodied by Ingrid Bergman during a post-mature stage of her life and career, hasn’t visited Eva for years. Her sudden appearance in Eva’s home brings under the spotlight the dissimilar characters of the two woman and their different perspectives all the same. Charlotte is a severe instructor who respects the formalistic lines, while Eva is an emotional woman, driven by her feelings in every possible direction.

Of course, the typical psychological phenomenon that induces a fragile imbalance between mothers and daughters is presented here. The picture’s gravity center, though, is rendered to a different spot. Like a sonata, the story is separated into three main chapters, reflecting a progression toward a certain end.

The end of an “autumn sonata” couldn’t be something different than a cold, heavy, and terminal winter. Charlotte, the story’s chilly and aging mother approaches a finale that Sven Nykvist indicates with his pale color selection. Eva, on the other side, represents a surviving sentimental bloom that reveals a subsequent dominion of spring and renaissance.

4. Long Day’s Journey into Night (2018)

Who could create more poetic films than a poet? Chinese director and poet Gan Bi returns after his 2015 long misty road of a movie called “Kaili Blues,” so as to engrave new canals in a labyrinthine mantle of ideas that suffuses a core of purely personal treasures and wounds. Heading back to the same haunts, as a perpetrator that returns to his crime’s territory, Bi draws his dream’s chilling shadows from his hometown‒ the small city of Kaili.

An attempt to follow the story’s plot on the superficial trends of a linear rationale would be as vain as to reorder David Lynch’s reveries on the surface of reality. The picture’s thick delusional idol of a past that is always reflected on a deforming mirror of the present can be comprehended only if one is willing to ignore the one-dimensional existence of time and perceive it as a melted creature that disjointedly overwhelmed the entire space-time continuum.

“Long Day’s Journey into Night” is a delirious, non-conformist and deeply personal dream of a road trip that revisits the original roots of its creator, as it explores the intertemporal impact of an old unfulfilled love.

Could a true love ever wear out? In the upside-down aspect of Bi’s sentience, the real feelings have painfully carved permanent grooves. If you mean to discover a solid grip somewhere inside the stunning yet fluid imagery of the film, you have to surrender to your own true and undimmed feelings.

3. Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975)

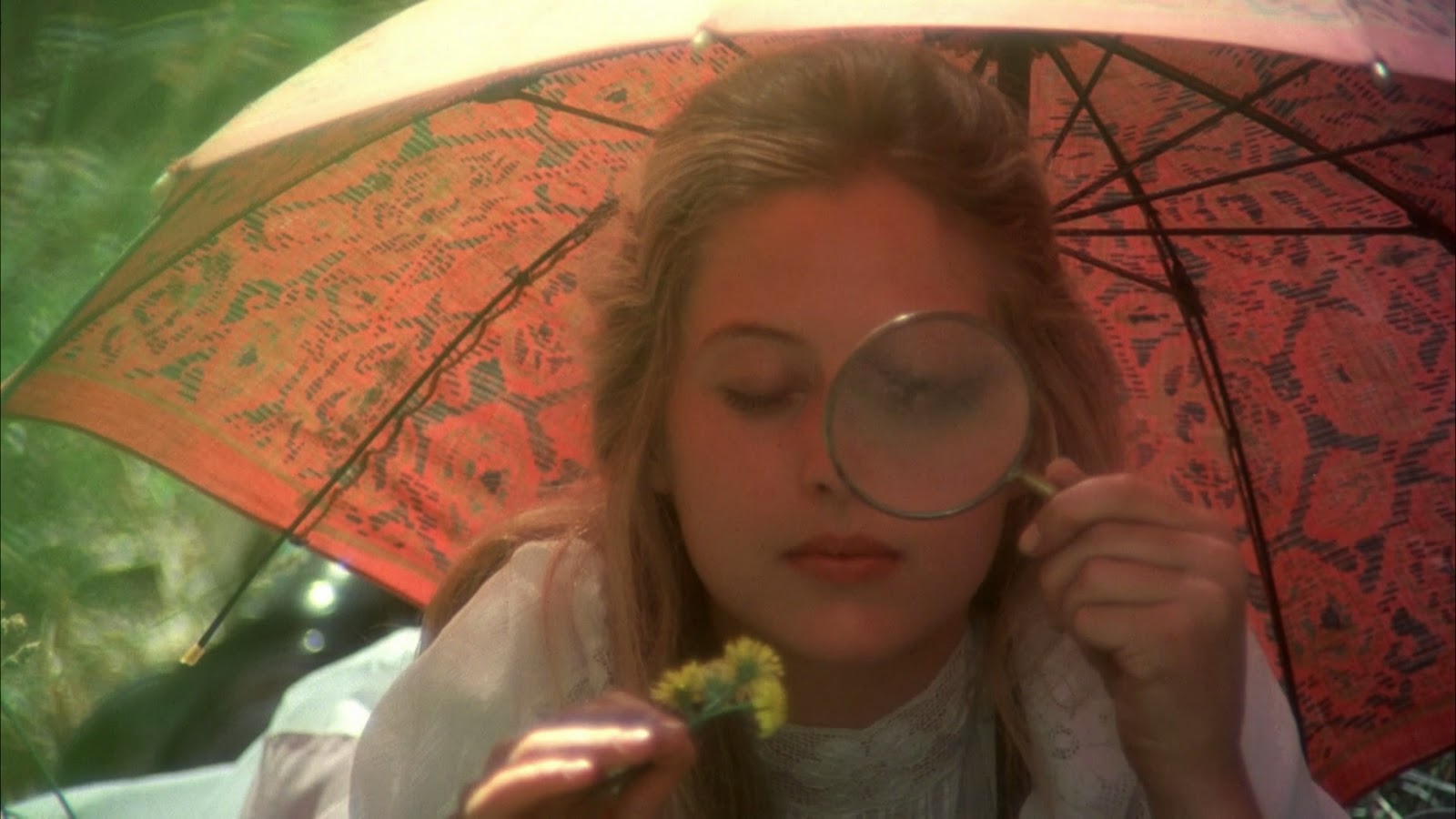

The ostensibly mysterious film “Picnic at Hanging Rock” by Australian director Peter Weir is an unsolved riddle of a realistic event if the viewer approaches its plot in a literal way. However, this story narrates one of the most beautifully portrayed and profound coming-of-age motion pictures, spinning inside an allegoric abyss of primal instincts and desires. The navigation through this intoxicating turmoil isn’t easy, but once the viewer dives in, its mesmerizing effect is ceaseless.

Australia, 1990. It’s Valentine’s Day, and a group of teenage girls that study in a conservative girl’s school heads toward an ancient ‒in terms of geological time‒ volcanic hill, for the purposes of recreation.

During their long way, the accompanying teacher describes how these black rocks occurred, back in a forgotten primitive past. Hot red lava erupted violently, she says, originating from the earth’s melted and trembling core. The girls listen ecstatically, looking at the terrifying tall rocks that stand still on the horizon.

As the girls rest and walk around the hanging rock, their teacher observes the most beautiful of them. Miranda looks like a renaissance Aphrodite, Miss McCraw admits, while she moves toward the hill, accompanied by three friends. The four girls wander as if in a dream, fearless and bewitched. One of them is soon terrified. An unidentifiable force leads her back to safety. Irma, another of them would be found after days in the mountains, whereas Miss McCraw gets lost in her search of the other two girls.

This fearsome, mysterious missing represents nothing more than a sexual awakening. During their course on the hanging rock, which was formed due to the earth’s endogenous urges, the girls were getting rid of their clothes one after another. When Irma returns back, she’s sexually activated but still in an immature stage. In one of the most beautiful scenes, she stands gracefully in a red dress, while a lot of white-dressed classmates attack her in a mood of rage and query.

Miranda, in her youthful and flawless beauty, represents renaissance. She wasn’t meant to come back. She was meant to satisfy her nature through a fair exchange of pleasure and archetypical fulfillment. On the other hand, her unnaturally strict and old-fashioned school represents conservation. The school principle admits that she loves a place where nothing changes. Ever.

2. Nostalgia (1983)

It’s very difficult to invent an accurate and at once descriptive definition for the word “nostalgia.” This short combination of letters carries a heavy and many-sided meaning, which as well involves many parameters of time, sentiment, and thought. There’s a quality of past in the concept of nostalgia, as it emits the intense sense of a primitive yet lyrical pain.

If all this could be mirrored on one man’s soul, it would definitely be Andrei Tarkovsky. From the oneiric collage of memories that emerges in “The Mirror” to the devastating return in a lost past that survives in his intelligent “Solaris,” Tarkovsky is an artist of clear mind and sheer sentiments that composes absolutely stunning and deeply sensitive visual poems.

“Nostalgia” is one more of his both self-explorative and self-exposing masterful works. Yet, despite the purely personal character of Tarkovsky’s filmography, his introspections concern every viewer that shares the same existential agonies, connections to the past and poetic tendencies. In this case, the disseminated melancholy of “Nostalgia” describes the suffering heart of those who are obliged to exist somewhere far away from their roots and beloved ones.

Andrei, the film’s hero, is a Russian immigrant in Italy. Standing behind the interactive cerebral window that cultures provide, he has decided to discover the footsteps of a Russian composer who lived during the 18th century. Through his healing quest for a foregone figure that represents his origins, Andrei manages to reach a high level of esoteric catharsis. As one of Tarkovsky’s cinematic alter-ego, Andrei resurrects a real discovery of an inner territory devoid of a geographic imprint.

1. The Weeping Meadow (2004)

They say that images can deliver the context of one thousand words. Theodoros Angelopoulos, perhaps the most important Greek film director of all-time, effortlessly fulfills this task through a direct, image-making language that touches the most fragile and injured strings of a vivid mind. His filmography is branded with numerous shots that, in their sincere beauty, carve a permanent sentimental and conscious imprint. Nevertheless, his absolutely poetic depiction of a traumatized community as it occurs in “The Weeping Meadow” is his most picturesque filmic creation.

The hovering populace of “The Weeping Meadow” left a land of death and misery and reached the hostile grounds that lie next to a river, somewhere in Northern Greece. Its simple, injured and misplaced people essentially strive for conquering a real territory for their future, which is clenched on a tearful past. But the misty waters of their temporary hometown swallow them down in its abyss, instead of providing the crystal-clear waters of a liberating river.

A couple of young people that remember their bleak life since that sudden disruptive flee from Odessa, is decided to move against the river flow so as to find its source— a source that perhaps hides their own lost original source. Instead of revealing the river’s sources, still, their overbold journey’s destination is found at a weeping meadow. Then, they both realize that the pursuit of a territory isn’t interwoven with the existence of a flowing source. We are all born by a weeping meadow that endlessly stands still.