6. Salo

Salo, or the 120 Days of Sodom is the most notorious entry on this list. It’s been banned for various lengths in various countries since its release in 1975 and attracts whispers of revulsion and fear whenever it’s mentioned in filmic conversation.

Transposing the setting of the Marquis de Sade’s novel from 18th-century France to the last days of Benito Mussolini’s regime in the Republic of Salo in 1944 (Salo standing in for Fascist Italy, of course), it focuses on a group of wealthy and corrupt libertines who kidnap 19 teenagers – nine boys and nine girls – and subject them to months of sadism, sexual violence and mental torture. Contained within the film are some truly shocking images: in the part of film titled ‘The Circle of Shit’, fecal consumption occurs in unflinching terms; scenes of horrific rape take place too.

The teenagers are treated akin to dogs, collared and controlled by the libertines as though they’re undertaking a particularly sadistic experiment. Pier Paolo Pasolini gives us no information about the tortured subjects in question; it was his intention to demonstrate the physical body as commodity.

The sex and abuse, then, are metaphors for the relationship between power and its subordinates, in this example between Fascism and its subjects. Salo is a great example of a filmmaker transferring his source material to his own means: the theme of sadomasochism, Pasolini shows, is eternal and universal, existing as it did in the 18th-century and even the 20th-century. By utilising the obscenity of Salo in an intellectual way, it transcends being merely pornographic to work as a strong critique of fascism, male dominance, and authoritative power.

7. Amour

Michael Haneke’s second entry on this list, Amour (2012) represents a sighting of humanity within the auteur’s usual parade of cold and calculated assaults on the Western bourgeois society he holds hatred for. Inspired partly by a similar situation that occurred in Haneke’s family, the narrative follows an elderly French couple, Anne and Georges, when Anne suddenly suffers a stroke which paralyses the right side of her body. His most accessible film by far, and most acclaimed as a result, Amour is still presented in a clinical and precise manner, like all his work: it’s a sparse and controlled chronicling of the disintegration of Anne.

Indeed, we are shown her dead at the beginning of the film, arranged so beautifully and peacefully on her bed. We therefore know where the narrative is ultimately heading, enhancing the discomfort in watching it all horribly and slowly unfold. He shoots the couple in long, unflinching shots, focusing on their faces, worn with time and weary of living. There’s never any open attempt to manipulate the emotions of the audience, with any emotive reaction coming from the realism of the narrative. The decay of the body in later years is universal, inescapable, and the horror unfolding onscreen impacts precisely because of this fact.

The 85-year-old and 82-year-old main actors portraying Anne and Georges, Emmanuelle Riva and Jean-Louis Trintignant, deserve extra acclaim for giving such powerful and moving performances; performances representing a frank and brutal contemplating of their own mortality (Riva sadly passed away five years later, in 2017). Perhaps their casting, Riva and Trintignant being two icons of the French New Wave period, could be read as Haneke’s sly nod to death and decline’s inevitability: all the chic and cool exuberance of youth will one day fade, and there’s no telling when it will come.

Amour equates to a profound statement on what love truly is. When we watch Georges tend to his wife for months, caring for her every need, we see not grand gestures of love, but the small moments that build to something momentous; we also are fully aware that his last despairing act, smothering his suffering partner, isn’t evil or inhumane but just one last gesture of affection and care. This is love imagined by Michael Haneke.

8. The Exorcist

Some films become near-mythical through the context of their creation, through the stories of how they came to be. The Exorcist (1973) is one such example. It’s rightly became not only a definitive horror piece, but a film classic in itself. The title is synonymous with terror, but what’s vital is how surprisingly well it holds up upon viewing today: even coming into it for the first time, The Exorcist still has the power and vision to provoke and horrify.

Adapted from William Peter Blatty’s 1971 novel of the same name, a work inspired by the alleged 1949 exorcism of Roland Doe (pseudonym), an anonymous young boy whose family became convinced that his aggressive and shocking behaviour was a result of demonic possession. It was one of three exorcisms conducted by the Catholic Church in the United States at this time, and even though sceptics concluded that the boy’s actions were more than likely to be due to his mental state of mind, the story still inspires intrigue and horror.

This context, real or not, is where the film draws much of its difficulty from: one, perhaps defined by their religion, can see The Exorcist and be overwhelmed by a historical account to test their faith; others will remain sceptical but be tested in other ways, shocked and repulsed by the idea of pure evil being possible on earth.

The film is many things, and reflects the audience’s own insecurities and fears. Learning of the techniques used on set by the director William Friedkin also elicit feelings of uncomfortableness; The Exorcist, in this respect, shares an affinity with that other difficult masterpiece Apocalypse Now (1979). He was prone to manipulating his actors to gain the reactions that he wanted. Indeed, some of the screams one hears in the film are the real painful screams of Ellen Burstyn and Linda Blair, who were yanked violently around in harnesses in key scenes.

Friedkin also slapped Father William O’Malley after asking him the priest if he trusted him, in order to generate a truly solemn reaction that was then used in the final cut. That some of the terror onscreen is partly real and true adds a layer to proceedings; it’s a complete commitment to creating the horror. This is how, while certainly a creepy supernatural film and a chilling genre piece, William Friedkin manage to create something to rise above these, moulding a timeless film that can shock and entertain most viewers.

9. A Clockwork Orange

One of Stanley Kubrick’s best and certainly one of his most controversial, A Clockwork Orange (1971) is a highly stylised, disgusting and degrading watch. Based on Anthony Burgess’s equally difficult master novel with the same title, both works question society and definitions of right and good.

Kubrick employed disturbingly violent images throughout and condemnation swiftly followed: Roman Catholics were forbidden from seeing the film by the National Catholic Office for Motion Pictures; the film’s influence was castigated by courts after the murder of an elderly homeless man by a teenager who informed the police that his friends had told him about a similar occurrence in A Clockwork Orange. They were wrong, of course, as Kubrick himself pointed out when rejecting the idea of art translating to life and being held responsible for actions but the sense of danger with the picture was evident.

It’s a disorientating experience, for example in the rape scene of the writer Frank Alexander’s wife, soundtracked by Gene Kelly’s musical classic ‘Singin’ in the Rain’. It’s a discomforting association, an attempt to make accessible the violence the viewer is witnessing. The use of songs like Kelly’s don’t make us enjoy the beatings and rape, however, but only serve to confound Kubrick’s audience more, in trying to separate the good from the bad.

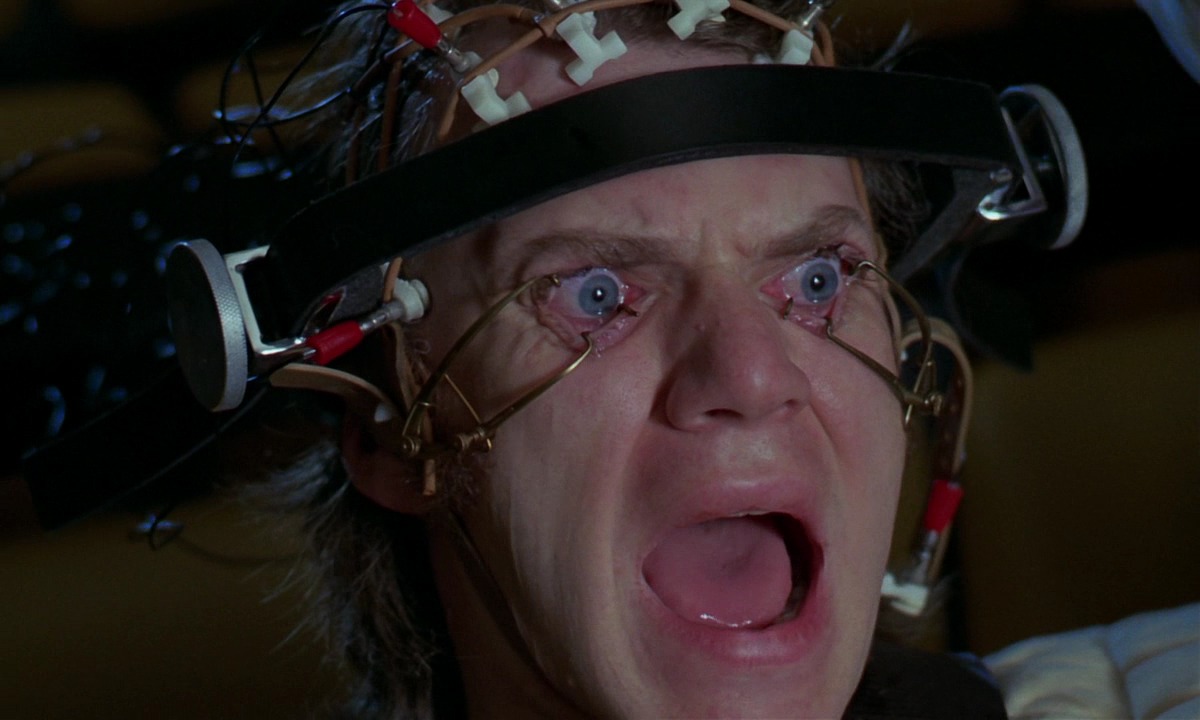

Indeed, all the horror contained in the film is layered with this otherwise cool and pleasing effect, like Kubrick signalling that this society is, simply, a violent and dark one: elegance and wickedness are just either side of the one coin. The main character, Alex DeLarge, is soon subjected to aversion therapy after much delinquency, becoming the good member of society, acting like clockwork.

It’s a false goodness, obviously, and this is where the social satire comes from: Burgess’s novel is a critique of behavioural psychology and conditioning. It’s an uncomfortable vision of a dystopian future Britain, but the narrative works as satire of contemporary society, then and now; governments are forever trying to control their subjects to greater levels, both left and right (A Clockwork Orange also attacks both sides of the political spectrum).

The lasting effect should be understanding Alex as a wicked person in a wicked world. He’s not unique, but just another bad subject like his parents, the policemen, doctors and all the politicians. The film is only a danger if reckoned with naively: that it’s drenched in Kubrick’s black humour, that the society is all bad, should make apparent it’s not something to be followed. It’s a cold and chilling nightmarish vision.

10. Son Of Saul

There are some film genres that have been nearly exhausted – think the prison film or the western – and the Holocaust is a historical period seemingly explored constantly. That’s what makes Son of Saul (2015) so frightening and incredible: it’s a wholly original and immersive account of a time experienced in numerous films before.

A first feature for Hungarian director Laszlo Nemes, it focuses on one man, Saul, a member of the Sonderkommandos, Jewish prisoners who helped the Nazis in the concentration camps in exchange for a little more time before their own deaths. Much of the difficulty in watching the film comes from its immersion in this hellish landscape.

The direction and cinematography offer a terrifying fictional insight into the extermination of the Jewish people in these awful places. It’s shot in unbroken takes and shallow focus, intensifying the action as Saul journeys throughout the camp. It’s disturbing to see how clinical the extermination is: there is no humanity, only business.

The narrative contains drama, as the film merges into a thriller: a body of a boy who survives the gas chamber, seemingly Saul’s own son, is ordered to be burned, but Saul instead tries to smuggle the body away so he can receive a proper burial with a Rabbi. This drama is never put at the service of entertainment, however, nor to elicit pure despair from the audience. It’s definitively Saul’s experience, his life or death.

This is what’s key to the greatness of Nemes achievement, it’s total avoidance of sentimentality. There is no attempt to explain proceedings or to understand the atrocities; they existed and that’s enough.

Aside from harrowing documentary footage of the Holocaust, Son of Saul feels like a close follower, a careful and considered treatment of the events, bringing the audience as close as would be possible. It is, then, a horror film in the truest sense of the word. When we approach touching and well-known subjects like this, finding new ways to comprehend it and deal with it, we as a society gain a little more from the experience.

Author Bio: Conor Lochrie is a Glaswegian currently travelling and working in New Zealand after 4 long and arduous years at university which he survived with a degree in Central and Eastern European Studies. Unsurprisingly, he now works in a warehouse but would much rather be watching and writing about cinema.